St Mary's Church, Chesham facts for kids

St. Mary's Church is a very old and important church in Chesham, Buckinghamshire, England. It's part of the Church of England. This church is built on a spot where people lived even in the Bronze Age, around 1800 BC. They even had a circle of special stones called puddingstones here!

Some parts of the church building are from the 12th century, which means they are over 800 years old! Over time, the church was changed and updated in the 15th and 17th centuries. This means it has a mix of different old English building styles.

By the 1800s, the church building was getting weak because of new parts added to its tower and many burials around it. Famous architects like George Gilbert Scott in the 1860s and Robert Potter later in the 20th century helped make the church strong and beautiful again.

Long ago, Chesham was a very large church area, and it even had two vicars (church leaders). This was because two important local families shared the right to choose the vicars. After some wars in the 1100s, this right was given to two different monasteries. Each monastery then chose its own vicar for Chesham.

Later, when monasteries were closed down in the 1500s, one half of the right to choose the vicar went to the Earls of Bedford. The other half was sold to different private owners. In 1769, the Duke of Bedford bought the other half, bringing the church back under one leader. From then on, St. Mary's had just one vicar.

In the 1800s, Chesham grew a lot. The church area was divided into four smaller, separate areas. But in 1980, people decided to bring them back together. So, by the 1990s, three of these areas were reunited under St. Mary's Church again.

Contents

Historical background

Chesham is a town in Buckinghamshire with about 20,000 people. It's located in the Chiltern Hills, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) northwest of London.

People have lived in this area for a very long time. There's proof of people living here around 8000 BC, farming around 2500 BC, and even a Bronze Age settlement around 1800 BC. This is when the stone circle of puddingstones was built in Chesham. Later, a tribe called the Catuvellauni lived here around 500 BC. Near Chesham, at Latimer, you can find remains of a Roman villa.

The first time Chesham was written about was in 970 AD. A lady named Ælfgifu mentioned "Cæstæleshamme" in her will, which means "the water meadow at the pile of stones." In the Domesday Book of 1086, Chesham was listed as "Cestreham" and had four mills.

Like many places in England, Chesham had religious disagreements in the 1500s and 1600s. In 1532, a man named Thomas Harding was executed in the town for his beliefs. From the 1600s, Chesham became a place where people who disagreed with the main church, called "dissenters," gathered. The first Baptist church opened in 1701, and Quakers have met here since the late 1600s. Even John Wesley, a famous preacher, visited Chesham in the 1760s.

Chesham Old Town is the oldest part of the town. It was the main center until the late 1800s. In 1851, about 2,500 people lived there. In 1889, the Metropolitan Railway arrived, and Chesham railway station opened. This station became the end of a 6.26-kilometer (3.89-mile) branch line from the main railway.

The new part of Chesham grew between the railway station and the Old Town. This meant the Old Town's old buildings stayed mostly the same. In 2009, the Old Town was added to a list of "Conservation Areas at Risk," meaning it needed special care to protect its history.

Architecture

The old stone circle shows that people worshipped here even before written history. While we don't have proof of a church before the Normans arrived in 1066, it's likely the Anglo-Saxons built a wooden church here. The first time a church in Chesham is mentioned in records is in 1153. In 1257, King Henry III allowed a yearly fair and weekly market in Chesham. The fair was held around the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which suggests the church was already named after Mary.

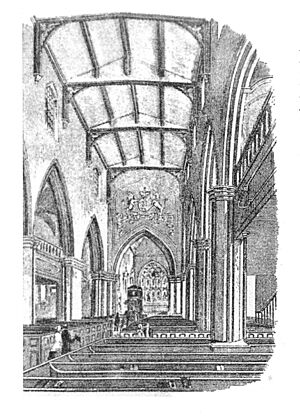

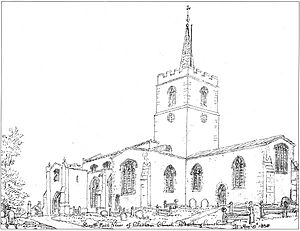

St. Mary's Church is built on the Bronze Age puddingstone circle. These ancient stones are now part of the church's foundations. The church is mostly made of flint stones with limestone decorations. It has a shape like a cross. The church today has a chancel (the area around the altar), a nave (the main part where people sit) with high windows, and side aisles. It also has transepts (the arms of the cross shape) and a porch at the south entrance. The church has a square tower with a pointed wooden spire covered in lead.

Even though the church has many Gothic styles from later times, a Romanesque window (an older style) shows that the church was already a stone building in the 12th century.

The whole church is about 34.7 meters (114 feet) long and 16.15 meters (53 feet) wide. The nave is about 19.66 meters (64 feet 6 inches) long and 6.7 meters (22 feet) wide. The side aisles and arches in the nave were added in the early 1200s. In the 1270s and 1320s, the arches of the tower were made wider. Around 1370, the chancel was rebuilt in a style called Decorated Gothic.

15th- and 17th-century renovation

In the 1400s, the high windows (clerestory) were added to the nave, along with a two-story south porch. These changes meant the door on the south aisle had to be moved. A large window and door in the Perpendicular style were also added to the western wall of the nave. Stained glass windows were put in the clerestory, but only small pieces of the old glass remain today. A staircase in the porch led to a small room above it. Local stories say that Thomas Harding was held in this room before he was executed in 1532. The porch also has a holy water basin from the late 1300s that is still there today.

The stone tower was finished in the 1400s, but we don't know exactly when the spire was built. It could be from the 1500s to the 1700s. We know the church had bells by the 1500s, as a list from 1552 mentions "v bells in the stepill" (five bells in the steeple). One bell, made around 1450, is still used today and is very important historically.

During the 1500s and 1600s, many churches in England, including St. Mary's, became damaged due to religious changes and wars. The great door of St. Mary's was damaged during the English Civil War, and you can still see bullet holes today. In 1606, people decided to fix up St. Mary's. Two of the bells were remade, the wooden benches (pews) were replaced, and a "fair new gallery" was built along the south aisle. In the 1700s, two more galleries were added. One was for "maids and maidservants," and another for the church's musicians and singers.

19th-century renovation

Since the tower arches were widened in the 1200s and 1300s, the tower of St. Mary's was not very strong. Adding bells and the lead-covered spire made it even heavier. Also, many people were buried inside and around the church, which further weakened the building. By the 1700s, the problems were so bad that part of the church was blocked off to try and make it stronger. The tower kept getting weaker, especially after new, heavier bells were added in 1812. Iron bands were put around the tower, but they broke. By the 1800s, large cracks appeared and were temporarily filled with bricks and rubble.

By 1867, the church leaders decided that the tower problems were serious enough for a big renovation. George Gilbert Scott, a famous architect who designed important buildings in London, was chosen to lead the project. Scott loved the Gothic style and wanted to make St. Mary's look more like its original Gothic design.

Scott removed the galleries, the old high-sided pews, and the three-tiered pulpit. The tower was made strong again, and the outside of the church was repaired with flint and limestone. The chancel was restored to its original shape and given a new east window with beautiful stained glass showing Faith, Hope, and Charity. New wooden pews and a Gothic-style pulpit were installed. A new font (a basin for baptisms) made of special stone was also added.

The north transept, which used to be a storage room, was used to house the church's organ. The south transept, which had been a private burial place for the Cavendish family, was opened up to the rest of the church. In 1890, special chimes were added to the tower clock to celebrate Queen Victoria's 60th year as queen.

20th-century renovation

Scott's changes worked well, and the church stayed mostly the same for about 130 years. Some changes included new stained glass in the chancel windows, showing knights, as a memorial to a young officer who died in the Boer War. A large painting was also added over the chancel arch, showing events from Holy Week set in the Chiltern Hills. In 1951, the church was given a "Grade A listed" status, meaning it's a very important historic building.

In 1980, one of the church bells was remade. By the 1990s, the inside of the church was thought to be not very practical for the community's needs. So, the interior was redesigned by Robert Potter in 1999. The west gallery was restored to hold the organ, and a kitchen and toilet were added. The north transept was turned into a vestry (a room for clergy) with a room above it. Underfloor heating was installed beneath a new marble floor, and the chancel step was replaced with a raised marble platform. Scott's old pews were removed and replaced with wooden chairs.

Ecclesiastical organisation

In the 1100s and early 1200s, the right to choose the vicar of the church was shared by two local landowning families. Since Chesham was a very large church area, having two leaders worked well. After the civil wars in the 1100s, there was a big increase in religious activity and monasteries grew. Before 1221, one family gave their half of the right to Woburn Abbey, and the other family gave their half to Leicester Abbey. From then on, Woburn and Leicester Abbeys shared the right, each choosing their own vicars for Chesham. These vicars were known as Chesham Woburn and Chesham Leicester.

After the monasteries were closed in the 1500s, the right to choose the Chesham Woburn vicar went to the Earl of Bedford. The right to choose the Chesham Leicester vicar was sold many times. Eventually, it was bought by the Skottowe family, who were important local landowners. From 1601 onwards, usually the same person was chosen as vicar by both sides, so the church had one vicar. In 1769, John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford, who had inherited the Chesham Woburn right, also bought the Chesham Leicester right. This meant the church area was officially unified by an Act of Parliament in 1767, and from then on, it had one vicar with assistants.

In 1845, Chesham became part of the Diocese of Oxford. The new bishop, Samuel Wilberforce, appointed Adolphus Aylward as vicar in 1847 to help reform the church area. A second church was opened in Waterside in 1867, and the large Chesham area was divided between St. Mary's and the new Christ Church, Waterside. As Chesham grew, the area was divided even more, creating four separate church areas: St. Mary's, Christ Church Waterside, St. John the Evangelist Ashley Green, and Latimer.

In 1980, it was decided to bring the church areas back together. Over the 1980s and early 1990s, three of the four areas were reunited into one large Chesham area. It is now led by one Rector (a main church leader) who is also the Vicar of St. Mary's, and a team of clergy who serve five other churches.

Associated buildings and structures

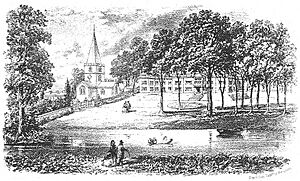

In 1712, a man named William Lowndes rebuilt Chesham's manor house, called The Bury. It's right next to the church. The building is still there today and is used as an office.

Because of its unusual history with two vicars, Chesham used to have two vicarages (houses for the vicars). The Upper Parsonage, also known as Bury Hill House, was built in the 1500s and was for the Chesham Leicester vicar. It was a large house just north of St. Mary's Church. In the early 1800s, it was bought and taken down.

The Lower Parsonage, for the Chesham Woburn vicar, was just east of the church. It was taken down around 1769 by the Duke of Bedford and replaced with a new vicarage for the unified church area. This vicarage is still used today and is called the Rectory.

Organ

In 1504, a will mentioned money for a chaplain who could "organise" and "sing well," which might mean there was an organ. However, the first clear record of an organ at St. Mary's is from 1852, when a William Hill & Son organ was installed. In 1869, during Scott's renovation, the organ was moved and made louder. In the 1999 renovation, the organ pipes were moved to the new west gallery and made better with electronics. The organ's control panel was placed at the eastern end of the north aisle.

Notable graves and memorials

The south transept used to be a private burial place for the Cavendish family. During Scott's renovations in the 1860s, it was opened up to the church. Only one Cavendish tomb remains today, belonging to John Cavendish, who died in 1617 at age 11. The tomb has fancy carvings and columns. The south transept also holds a pyramid-shaped tomb from 1726 for Lady Mary Whichcote.

Richard Bowle, who helped with the 1606 church restoration, has a black marble monument on the north side of the chancel. It mentions his "faithful service of divers great lords."

On the north wall of the sanctuary is a large memorial to Richard Woodcock, who was vicar of both Chesham Woburn and Chesham Leicester from 1607 to 1623. It has a painted bust of Woodcock holding a book and a long inscription in Latin and English. It calls him "The hammer of heretics." Woodcock was very popular, and when he died, people took turns carrying his coffin to the church. Near his memorial is one for Nicholas Skottowe, put up in 1800. It's a stone sculpture of a sad woman kneeling over a tomb, described as "remarkably tender."

During Scott's renovations in the 1860s, all burials inside the church were removed. However, during the 1999 renovation, a hidden vault was found near the center of the church. It had a brass plaque saying "The Family Vault of Robert Ward." Inside were the coffins of Catherine Julia Ward and her three-year-old son, Charles Robert Ward. The vault has been sealed again and remains in place.

Adolphus Aylward, the vicar from 1847 to 1872 who oversaw the church area changes, is remembered by a brass plaque and a stained glass window. His daughter Julia died in 1862 at age 15 and is buried in the churchyard. Her grave was planted with snowdrops, which still bloom every spring. Julia Aylward is also remembered by a piece of stained glass in a window at the west end of the north aisle.

A memorial to Thomas Harding, a Lollard martyr, stands in the churchyard near the south chancel. It was put up in 1907. The base of the cross says he "laid down his life for the word of God" on May 30, 1532. Harding was executed nearby and is believed to have been held in the church's porch room before his execution. An old book describes his execution, noting that people were told that bringing wood to burn those with different beliefs would grant them special permission for a period of time. Near Harding's memorial is an old gravestone showing a teacher and children, believed to be the grave of Daniel King, who taught in Chesham's first Sunday School.