Wigwag (railroad) facts for kids

A wigwag is a special type of railroad crossing signal. It got its name because it swings back and forth like a pendulum, warning people that a train is coming. These signals were once very common in North America.

The wigwag signal was invented in 1909 by Albert Hunt. He was an engineer at the Pacific Electric (PE) railroad in Southern California. He created it to make railroad crossings safer for everyone. It's important not to confuse this "wigwag" with the term used in Britain, which usually means flashing lights at modern crossings.

Contents

Why Wigwags Were Needed

When cars became popular, they traveled much faster. Also, many early cars were enclosed, making it hard for drivers to hear or see trains approaching. This led to more accidents at railroad crossings.

Before wigwags, many crossings had a watchman. This person would wave a red lantern from side to side to signal "stop" when a train was near. This "stop" motion was understood everywhere in the U.S. The idea was to create a machine that could do the same thing. This mechanical "flagman" would clearly warn drivers and pedestrians.

How Wigwags Were Designed

The first wigwags used by Pacific Electric had gears, but they were hard to keep working. The final design was much better. It was first put in place in 1914 near Long Beach, California. This new design used electromagnets that pulled on an iron arm.

A red steel disc, about 2 feet (610 mm) wide, was attached to this arm. This disc acted like a pendulum. In the middle of the disc was a red light. Every time the disc swung, a mechanical bell would ring. This new signal combined sight (the swinging disc and light), motion (the swinging), and sound (the bell) to give a clear warning.

This new signal was called the magnetic flagman. It was made by the Magnetic Signal Company in Los Angeles, California. After these unique signals were installed, train and car crashes at PE crossings went down. These signals became very well-known in Southern California. Their popularity grew, and Magnetic Signal wigwags appeared at railroad crossings all over the United States, Canada, Mexico, and even as far away as Australia and Europe.

Different Types of Wigwags

Magnetic Signal Company made three main types of wigwags:

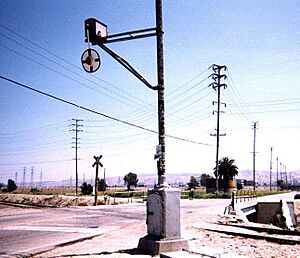

- Upper-quadrant: This model was placed directly on top of a steel pole. The swinging disc waved above the motor box. It was used in places where there wasn't much space. You can see an accurate computer animation of this type of signal in the 2006 movie Cars.

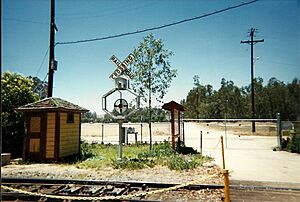

- Lower-quadrant: This version waved the disc below the motor box. It was often designed to hang over the road from a pole. Some railroads, especially in the northwestern U.S., put their lower-quadrant signals directly on tall steel poles, similar to the upper-quadrant type. These often had "RAILROAD CROSSING" signs (crossbucks) on top. A lower-quadrant signal like this appears in the 2004 film Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events.

- "Peach Basket": This was the least common type. It was a pole-mounted lower-quadrant signal. The motor box was fixed to the top of an octagonal steel frame that went around the swinging disc. This frame was probably to protect the signal from being hit by vehicles. It was called the "peach basket" because of this protective frame. Most "peach basket" signals were used by the Union Pacific Railroad. Some versions had the word "stop" light up on the banner.

The Magnetic Flagman wigwag works by using large, black electromagnets. These magnets pull an iron arm back and forth. Sliding contacts switch the electric current from one magnet to the other, making the disc swing. Each Magnetic Flagman also had a small plate showing when it was patented and how much power it needed.

Powering the Signals

Wigwags could be ordered to work with different types of electricity. They could use 8 volts DC (direct current), which was standard for railroad signals. Or, they could use 600 volts DC, which was used to power streetcars and electric trains. Most of the 600-volt units were used by Pacific Electric. When PE stopped running passenger trains in 1953, these 600-volt wigwags were slowly changed to use 8 volts DC.

Some Magnetic Flagman models also used 110 volts AC (alternating current). These were used on railroads like Norfolk and Western. AC power didn't create as much pulling force, so these signals had a special device. It used all four magnets to get the signal swinging, then two magnets would turn off, and the remaining two would keep it moving.

Special Features and Changes

Railroads could order various options for their wigwags. One option was a round, counterbalancing "sail" for use in windy areas. This sail was sometimes painted like the main disc. There was also a warning light with an adjustable cover. Another option was an "OUT OF ORDER" sign that would drop into view if the signal lost power.

A rare adjustable mount was available to help aim the signal correctly if it couldn't extend fully over the road. The last known example of this mount was removed in Gardena, California, in 2000. Most of the versions with warning signs were sent to Australia. One is now on display at the Newport Railway Museum in Melbourne, Australia.

In the early 1930s, the U.S. government made a rule about the wigwag's disc. It had to be changed from solid red to a black cross and border on a white background. Later, another rule required alternating red lights, like those used today. Because of new rules about crossing signals and their power needs, wigwags were no longer installed after 1949. However, older laws allowed existing wigwags to stay until their crossings were updated. The Magnetic Signal Company was sold after World War II. They continued making new signals until 1949 and replacement parts until 1960.

The black cross on a white background became a common traffic sign in the U.S. to warn drivers about unprotected crossings. It was even part of the Santa Fe Railroad's logo. Today, this symbol is still used, but with a yellow background and the cross rotated into an "X."

Wigwags Today

Very few wigwag signals are still in use today. Their numbers keep shrinking as crossings are updated and spare parts become hard to find. Once, old wigwags were sold for scrap metal. Now, they are valuable collectibles for railroad fans and collectors. Wigwags made in Minneapolis, Minnesota, after production moved from Los Angeles, are especially rare and prized by collectors.

In 2004, there were over 215,000 railroad crossings in the U.S. Only 1,098 of them still had one or more wigwags. This was a big drop from 1983, when there were 2,618 crossings with wigwags. Most of the remaining wigwags are in California, Wisconsin, Illinois, Texas, and Kansas.

The last wigwag on a main rail line was removed in March 2021 in Delhi, Colorado. In Anaheim, California, a working signal was removed in February 2019. This signal might have even been in the 1922 Magnetic Flagman catalog!

A single lower-quadrant wigwag in Vernon, California, protected a crossing with eight tracks. This signal was removed in April 2020. Its removal, along with the Anaheim signal, marked the end of Southern California wigwags still in regular service.

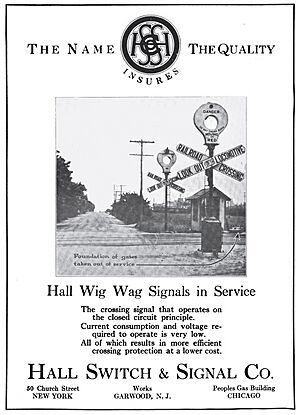

Other Wigwag Makers

Wigwags were also made by other companies, like Western Railroad Supply Company (WRRS) and Union Switch and Signal (US&S).

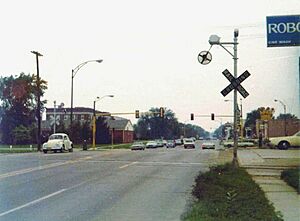

WRRS wigwags, especially the "Autoflag #5" model, were common in the Midwest. They worked similarly to the Magnetic Flagmen, using electromagnets to swing an illuminated banner. Unlike Magnetic Flagmen, WRRS wigwags used separate bells mounted on the pole.

Autoflag #5s were widely used on many railroads, including the Chicago & North Western and Illinois Central. Most of these wigwags were removed in the 1970s and 1980s as crossings were modernized. They came in both lower-quadrant and a "center harp" style, similar to the Magnetic Flagman's "peach basket." Some early Autoflag #5s had banners that would hide behind a shield when not active.

US&S wigwags were mainly used in the northeastern U.S. and a few other places. Their design was a bit different, using a drive shaft to make the banner swing. Some of them even had "chase lights" above the banner that moved to show the swinging motion. While most US&S wigwags are gone, one still works in Joplin, Missouri, on an old industrial track.

In Canada, two WRRS Autoflag #5 wigwags were in service near Tilbury, Ontario, until 2011. These had "disappearing banners," which was the only style approved in Canada.

In Point Richmond, California, two upper-quadrant wigwags became a local issue in 2001 when the railroad wanted to remove them. However, in 2019, the community raised money to restore them. These two wigwags are the last of their kind paired together in active use. They now work only for special events and are mostly decorations, alongside modern gates and lights. Signs are posted to let people know they are not the primary warning signals.

On the TV show American Restoration in 2013, a pair of WRRS Autoflag #5 wigwag signals were restored for the Nevada Northern Railway Museum. In Australia, a wigwag is preserved along an old railway line in Mount Barker, South Australia.

Preservation

Many wigwag signals have been saved and are now displayed at railroad museums and heritage railroads. Here are some places where you can see them:

- Arizona Railway Museum

- California State Railroad Museum

- Colfax Railroad Museum

- Colorado Railroad Museum

- Conway Scenic Railroad

- East Troy Electric Railroad

- Edaville Railroad

- Elgin County Railway Museum

- Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum

- Hoosier Valley Railroad Museum

- Illinois Railway Museum

- Mid-Continent Railway Museum

- Monticello Railway Museum

- Nevada Northern Railway Museum

- North Carolina Transportation Museum

- Orange Empire Railway Museum

- Oregon Electric Railway Museum

- Port Adelaide National Railway Museum

- Rosenberg Railroad Museum

- San Luis Obispo Railroad Museum

- Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum

- Virginia Museum of Transportation

- Western Pacific Railroad Museum

- Whippany Railway Museum

- Old Prairie Town

- Texas Transport Museum

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |