Aftershock facts for kids

An aftershock is a smaller earthquake that happens after a much bigger one, called the main shock, in the same area. Think of it like a ripple effect after a big splash. Aftershocks are the opposite of foreshocks, which are small earthquakes that happen before the main shock. They occur because the Earth's crust around a fault (a crack in the Earth's surface) is still settling down after the main earthquake.

Sometimes, after a big earthquake and its aftershocks, people might feel like the ground is shaking even when it's not. This feeling, sometimes called "earthquake sickness," is a bit like motion sickness. It usually goes away as the ground stops moving so much.

Where do aftershocks happen?

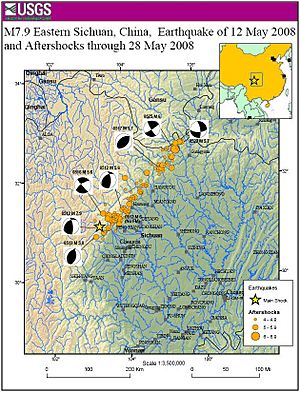

Most aftershocks happen in the same area where the main earthquake's fault line broke. They can occur right along that fault or on other smaller faults nearby. Usually, you can find aftershocks up to a distance equal to how long the main fault line broke.

Why are aftershocks dangerous?

Aftershocks are risky because they are hard to predict. They can also be quite strong themselves. They are especially dangerous because they can cause buildings that were already damaged by the main earthquake to collapse.

Bigger earthquakes usually have more aftershocks, and these aftershocks can be larger too. Sometimes, a series of aftershocks can last for years, especially if the main earthquake happened in an area that doesn't usually have many earthquakes. For example, the land around the New Madrid fault in the central United States moves very slowly, only about 0.2 millimeters a year. This is much slower than the San Andreas Fault in California, which moves about 37 millimeters a year.

What are foreshocks?

Foreshocks are small earthquakes that happen before a larger one. Some scientists have tried to use foreshocks to help predict earthquakes. One of their few successful predictions was the 1975 Haicheng earthquake in China. However, in other places like the East Pacific Rise, certain types of faults show more predictable foreshock patterns before a big earthquake.

Scientists who study earthquakes, called seismologists, use special tools and models, like the Epidemic-Type Aftershock Sequence (ETAS) model, to understand aftershocks better.

See also

In Spanish: Réplica (sismología) para niños

In Spanish: Réplica (sismología) para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |