Alexander Monro Primus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Monro Primus

|

|

|---|---|

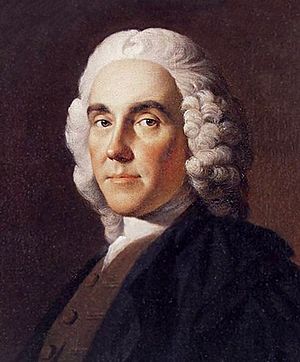

Alexander Monro by Allan Ramsay (1749)

|

|

| Born |

Alexander Monro

19 September 1697 London, England

|

| Died | 10 July 1767 (aged 69) Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Known for | Foundation Professor of Anatomy, Edinburgh University Medical School |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Professor of Anatomy |

| Institutions | University of Edinburgh, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh |

| Notable works | The Anatomy of the Human Bones |

Alexander Monro (born September 19, 1697 – died July 10, 1767) was an important Scottish surgeon and expert in anatomy. His father, John Monro, was a surgeon who dreamed of creating a medical school in Edinburgh. He made sure Alexander received the best education, hoping he would become the first Professor of Anatomy there.

After studying medicine in Edinburgh, London, Paris, and Leiden, Alexander Monro returned home. He became a successful surgeon and anatomy teacher. With his father's help and the support of Edinburgh's leader, George Drummond, Alexander Monro was chosen as the first Professor of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh. His lectures were very popular because he taught in English, not the usual Latin. His skill as a teacher greatly helped the new Edinburgh medical school become famous.

He is often called Alexander Monro Primus or Senior. This helps tell him apart from his son, Alexander Monro ("Secundus"), and his grandson, Alexander Monro ("Tertius"). Both of them also became anatomy professors after him. Together, these three Monros held the University of Edinburgh's Anatomy Chair for an amazing 126 years!

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Alexander Monro was the son of John Monro and Jean Forbes. His father was a military surgeon, and Alexander was born in London while his father was working there. When Alexander was three, his family moved back to Edinburgh.

His father was very keen on Alexander's education. He made sure Alexander learned Latin, Greek, French, philosophy, math, and even how to keep financial records. Alexander attended classes at the University of Edinburgh from 1710 to 1713.

After this, he became an apprentice to his father, who was a surgeon in Edinburgh. During this time, Alexander also took classes in botany and chemistry. He learned about anatomy by watching dissections at Surgeons Hall. In 1715, he even helped his father treat wounded soldiers after the Battle of Sheriffmuir.

Studying Abroad: London, Paris, and Leiden

In 1717, after finishing his apprenticeship, Alexander Monro went to London. He studied anatomy with William Cheselden, a very famous surgeon and teacher. They became lasting friends.

To gain more experience, Monro lived with an apothecary (like a pharmacist who also treated patients). He visited patients with him and attended lectures on science and philosophy. He was very good at dissecting bodies, both human and animal. Once, he got a bad scratch while dissecting a lung from someone with tuberculosis. His arm almost had to be removed due to infection.

Monro actively joined discussions and started sketching ideas for his book on bones. Before leaving London, he sent some of his dissected specimens home. People in Edinburgh were so impressed that one professor, Adam Drummond, offered to give up his teaching position for Monro.

In 1718, Alexander Monro went to Paris. He attended botany lectures and visited hospitals like Hotel Dieu. He learned about anatomy, surgery, and even how to deliver babies.

On November 16, 1718, Monro became a student at Leiden University in the Netherlands. He studied with Herman Boerhaave, a great doctor and teacher. Boerhaave recommended he visit Frederik Ruysch, an anatomy professor in Amsterdam. There, Monro saw a huge collection of dissections and learned how to preserve anatomical specimens. Many Scottish students, including Monro, did not take the final exams for a medical degree at Leiden.

Becoming a Professor of Anatomy

When Monro returned to Edinburgh in 1719, he passed the exams to become a Fellow of the Incorporation of Surgeons. He was officially admitted on November 19. As promised, Adam Drummond and John M'Gill gave up their professorships for him.

The Incorporation of Surgeons supported Monro, and on January 22, 1720, the Town Council appointed him Professor of Anatomy. He received a small salary of £15, plus student fees.

At first, Monro's position was temporary. But his teaching was so popular that in 1722, he asked the Council for a permanent role. On March 14, 1722, they named Alexander Monro the sole Professor of Anatomy for the City and College.

Until 1725, Monro taught at the old Surgeons' Hall. His popular classes meant more bodies were needed for dissection. Even though Monro said he hated "stealing human bodies out of their graves," the public was angry at anatomists. This led to protests and riots. Monro felt unsafe and worried about his collection of specimens. He asked the Town Council to let him teach inside the University, which was safer. They agreed, and Monro moved to the University of Edinburgh, starting there on November 3, 1725.

The medical faculty was completed in 1726 with the appointment of other professors. These included John Rutherford for the practice of medicine and Andrew Plummer for chemistry.

Creating a Teaching Hospital

John Monro, Alexander's father, had a vision for the new Edinburgh medical school. He wanted it to be like the Leiden model, with a medical faculty and a teaching hospital. In 1721, Alexander Monro wrote a pamphlet explaining why Edinburgh needed such a hospital.

Lord Provost George Drummond helped raise money from local surgeons, doctors, wealthy citizens, and churches. In August 1729, Monro and other donors opened a small hospital in a rented house. It had six beds for poor, sick people. This "Hospital for the Sick Poor," or "Little House," was where medical students could learn by treating patients. This was the beginning of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

In 1736, King George II gave the hospital a Royal Charter, adding "Royal" to its name. The medical school grew quickly, and the small hospital became too crowded. A new, larger hospital was designed by the famous architect William Adam. The hospital moved in 1741, and the new building was finished in 1745.

One of the first groups of patients in the new hospital were soldiers wounded at the Battle of Prestonpans in 1745. Monro Primus, who supported the British Crown, treated wounded soldiers from both sides of the battle.

The Anatomy of the Human Bones

In 1726, Monro published his most important textbook, The Anatomy of the Human Bones. This book was very successful, going through eight editions during his lifetime and three more after he died. Later versions also included details about The Anatomy of the Human Nerves.

The book was translated into many European languages. In 1759, a French edition was published in Paris with beautiful pictures by Joseph Sue. Thomas Thomson, a botanist, said that Monro's book was so complete that it would be "perfectly unnecessary to introduce any improvements."

Monro's book greatly increased the fame of Edinburgh's new medical school. In 1764, he retired from his professorship but continued to give clinical lectures at the hospital. That same year, he published a report on smallpox vaccination in Scotland.

Learned Societies and Contributions

As a Fellow of the Incorporation of Surgeons, Monro continued his surgical work alongside teaching anatomy. Like his son and grandson, Monro Primus was also a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

On June 27, 1723, Monro was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society because William Cheseldon recommended him.

In 1731, Monro was key in starting the Society for the Improvement of Medical Knowledge. He became its first secretary. The next year, the Society began publishing Medical Essays and Observations, with Monro as the editor. This journal published six volumes of medical cases, reviews, and book summaries. Most of the reviews were written by Monro himself.

This journal was very popular and important. It was translated into French, German, and Dutch. Medical Essays and Observations is considered the first regular medical journal in Britain and one of the first in the world. It was also the first medical journal to use anonymous peer review, where experts check articles without knowing the author's name. This new publication helped make Monro a major figure in the Scottish Enlightenment, a time of great intellectual and scientific growth.

After a break, the society became the Philosophical Society. It also stopped for a while but was restarted in 1752 with Monro and the philosopher David Hume as joint secretaries. In 1783, the Philosophical Society received a Royal Charter and became the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Monro was also a member of the Select Society, which aimed to improve the country.

In 1765, Monro published a report on how many people in Scotland had received the smallpox inoculation. He estimated that only 88 out of about 270 doctors in Scotland had used the procedure, inoculating a total of 5,554 people.

Family and Later Life

In 1725, Alexander Monro married Isabella MacDonald (1694-1774). They had three sons and one daughter.

Their eldest son, John Monro (1725-1789), became a lawyer. The second son, Donald Monro (1727–1802), became a doctor and a Fellow of the Royal Society. The third son, Alexander Monro Secundus (1733–1817), followed his father as Professor of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh.

Monro Primus wrote a book called An essay on female conduct for his only surviving daughter, Margaret (died 1802), to help with her education.

From 1730, Monro lived in a large apartment on the south side of the Lawnmarket. In 1750, he moved to Covenant Close off the High Street.

Death

Alexander Monro Primus died at his home in Edinburgh on July 10, 1767, from rectal cancer. He is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard in central Edinburgh with his wife and son, Alexander.

Works

- Osteology, A treatise on the anatomy of the human bones with An account of the reciprocal motions of the heart and A description of the human lacteal sac and duct – Online: the 1741 edition.

- An account of the inoculation of small pox in Scotland. Edinburgh:1765, printed by Drummond and J. Balfour ….

- An essay on female conduct. 1739.