Allied Troop Movements During Operation Michael facts for kids

In March 1918, during World War I, Germany launched a huge attack called Operation Michael on the Western Front. This was the first part of their "German Spring Offensive." Germany had just made peace with Russia, so they moved many of their soldiers from the Eastern Front to the Western Front. Their goal was to win the war quickly against France and Britain.

The attack almost succeeded! It was a very dangerous time for the Allied forces (Britain and France). But a few days into the battle, on March 26, a French general named Ferdinand Foch was put in charge of all Allied armies. This important decision helped turn the tide of the war.

Contents

Why the Attack Happened

At the start of 1918, things weren't going well for Britain and France. The British army had just been through a very costly battle called the Battle of Passchendaele. The French soldiers were also tired and unhappy after another tough fight, the Nivelle offensive. American troops were slowly arriving in France, but not enough to make a big difference yet.

General Haig, who led the British army (called the B.E.F.), wanted more soldiers. He believed that fighting hard, even with losses, would eventually wear down the German army. However, the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, didn't want to ask for more people to join the army or take workers away from important jobs. He thought the British army would have to manage until more American soldiers arrived, maybe for a big attack in 1919.

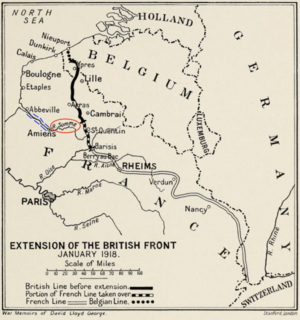

Meanwhile, the French Prime Minister, Clemenceau, was worried. Many French soldiers were nearing the end of their service. He asked the British to take over an extra 25 miles of the front line, which they did in January 1918. This new area was held by the British Fifth Army, led by Hubert Gough. This part of the front, known as "The Fifth Army Front," was not well-prepared for defense. Its natural barrier, the Oise River, had even dried up. Sadly, this was exactly where the Germans planned their main attack.

The German Attack

In the early morning of March 21, 1918, German cannons began firing heavily on the Western Front. Then, a massive German attack, with nearly 200 divisions (large groups of soldiers), hit the weakest part of the Allied line.

Just two months earlier, in January, Allied leaders had guessed where the attack would happen. They had even ordered 30 divisions to be kept ready as a "reserve" (extra soldiers) to deal with it. But General Pétain (French) and General Haig (British) ignored this order. By March 15, it was too late to change anything.

The Germans had been planning this huge attack for months. When it happened, it caught the Allies by surprise. The Germans used clever tricks to hide their plans. General Pétain in France thought it was just a small attack to distract them, believing the main attack would be much further south. In England, Prime Minister Lloyd George was told for the first two days that it might just be "a big raid."

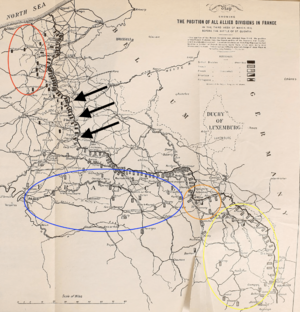

If the generals had followed orders and kept the reserve soldiers ready, they would have been exactly where they were needed. But General Haig's reserve divisions were far north, near the English Channel ports (see Map #1, red circle). General Pétain refused to use his reserves because he thought the main attack would be elsewhere. This meant it would take a long time – sometimes months – to move soldiers into position.

Within days, the German attack broke through the front line over a 50-mile area. On March 24, General Pétain ordered his army to retreat and protect Paris. The next day, General Haig planned for the British to retreat towards the English Channel. The Germans were very close to winning the war.

Allied Soldiers Move

British and French Armies

The British Fifth Army, led by General Hubert Gough, faced the strongest part of the German attack. This was the weakest part of the British line (see Map #3). General Haig kept most of his reserve soldiers far north, near the English Channel (see Map #1, red circle). This left Gough with only 17 divisions on the front line and 2 more behind them. The Fifth Army was attacked by 50 German divisions and was outnumbered three to one. It couldn't hold the line.

There was a serious worry that the British and French armies would be completely separated. Allied leaders in Paris and London didn't realize this was the huge attack they feared until March 23. To help each other, Generals Pétain and Haig had made a verbal agreement a month earlier to support each other if needed.

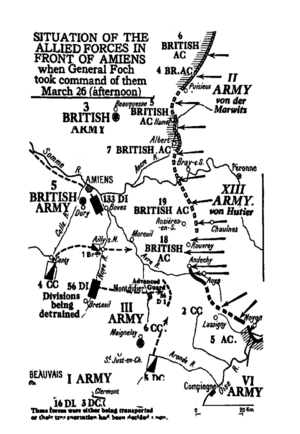

On the evening of March 21 and early March 22, General Haig asked General Pétain for 3 divisions to help Gough. Pétain quickly agreed, sending the French Fifth Corps (3 divisions) to reinforce the British. These soldiers were moved by trucks and started arriving on March 23. By March 26, seven French divisions and one British division were fighting in the British Fifth Army area. They arrived bit by bit and without their heavy cannons.

On the afternoon of March 22, General Haig asked for 3 more divisions. General Pétain responded by sending his entire Third Army (3 more divisions). That evening, General Haig, believing he was being attacked by 81 German divisions, asked Pétain for his entire Fifth Army (20 more divisions). He also asked the French to take over the British area south of the Somme River (see Maps #3 & 4) and for Pétain to take command of Gough's Fifth Army.

However, General Pétain was sure that only 26 divisions were attacking Haig, and the other 55 were about to attack him. Because of this, he kept his reserve soldiers near Champagne. He ordered his First Army, which was much further south, to move to the battle area. This caused delays. General Pétain did agree to take over the entire battle area and put General Fayolle in charge of the 12 divisions now moving there.

By March 23, Gough's Fifth Army and the British Third Army were being pushed back. The French Prime Minister, Clemenceau, visited General Pétain twice and returned convinced that the government might have to leave Paris. As the first French reserve soldiers arrived, they were immediately sent into the fight.

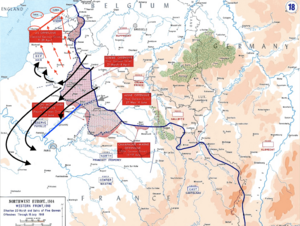

At 4 PM, Haig and Pétain met. General Haig again asked for 20 French divisions to gather around Amiens, along the Somme River. This would stop the Germans from surrounding his army and keep open a path to the English Channel ports (see Map #2). General Pétain, who still had 30 divisions in his reserve, refused. He wanted to keep these soldiers to protect Paris. At this point, both sides started thinking about their own country's safety more than the overall Allied effort.

On March 24, the French reserve soldiers arriving couldn't hold the line or stay connected with the British. General Pétain kept his reserves near Champagne. He ordered 6 more divisions (making 18 in total) from further south to move behind the battle area to stop the Germans from advancing inland. This also caused delays. By evening, the gap between the French and British armies was so wide that General Pétain ordered General Fayolle to keep his link with the French at all costs, and to link with the British only "if possible."

Pétain then visited General Haig at 11 PM. He told Haig that if the British continued to pull away from the French, he would have to pull his own armies back to protect Paris. Orders for this were already given. General Haig, still thinking the British army was facing the entire German army, asked Pétain if he would abandon them. Pétain replied, "It is the only thing possible."

After lunch on March 25, a French official estimated the chances of an Allied defeat at 90%. General Pétain corrected him, saying it was 96%. Pétain then suggested that the Prime Minister should ask for peace. Later that afternoon, General Pétain was planning how to move his armies to protect the capital. He imagined the British and French armies separating, with the British falling back to defend their supply routes near the English Channel, and the French having to stretch their army to the ocean behind the British lines. This would lead to battles north of Paris, and if France lost, Paris would be abandoned. To prevent this, the capital had to be defended right away, and orders were given.

American Soldiers

On the morning of March 25, a call was made to General Pershing, who led the American forces, asking for all the help he could give. Pershing said, "I'm coming over." The French waited all day for him. Finally, at 10:45 PM, Pershing arrived, delayed by traffic and refugees.

In a meeting, Pershing agreed to lend General Pétain his 4 American divisions (which were as strong as 8 French divisions). Pétain would use these American soldiers in place of his own, allowing him to send his experienced French divisions to the battle. However, these American troops were also coming from further south and would take time to arrive. One American division went directly to fight with the British, while the three less trained ones took their place in the French line.

With American help, General Pétain now had a total of 24 divisions to send into action. The biggest problem was time. It usually took two days by train to move one division, and even with trucks, it would still be slow. Moving 24 divisions could take two months, and that didn't include the heavy cannons, which took even longer. This delay was a big worry for the generals and Prime Minister Clemenceau, especially since they had earlier opposed forming an Allied General Reserve that would have been ready to stop the attack.

What Happened Next

Luckily for the Allies, several secret meetings were held. These meetings led to the French General Ferdinand Foch being chosen as the supreme commander of the Western Front. These important meetings, held in Paris, Compiègne (French Headquarters), and Doullens, stopped any ideas of retreating and helped bring the war to an earlier end.

General Foch made a map on March 26, 1918, showing where all the Allied soldiers were. This map was later published in his autobiography. It shows that all the divisions south of the Avre River were French (arriving), the general position of the British V Army (which had retreated northwest), and the broken line west of Amiens, along the Somme. This was where General Haig had asked for 20 French Divisions to protect the British army's side, as it had to "fight its way slowly back covering the Channel Ports." The map also shows the British III Army, which had moved its right side along the Somme River after the V Army retreated. It was gathering soldiers there to defend against a German attack and had plans to fall back to Arras if needed.

Images for kids

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |