Alvise Cadamosto facts for kids

Alvise Cadamosto (also known as Luís Cadamosto in Portuguese) was an explorer and merchant from Venice, Italy. He was hired by Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal and made two important trips to West Africa in 1455 and 1456. He traveled with another captain named Antoniotto Usodimare.

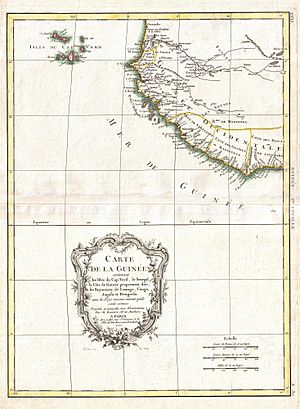

Cadamosto and his companions are famous for discovering the Cape Verde Islands. They also explored the coast of Guinea, from the Gambia River to the Geba River. These were the biggest discoveries made by Prince Henry's explorers since 1446. Cadamosto wrote detailed notes about his journeys and the people he met in West Africa. These notes are very helpful for historians today.

Contents

Early Life

Alvise was born in Venice, Italy, in a palace called Ca' da Mosto, which is where his name comes from. His father, Giovanni da Mosto, was a government worker and merchant. His mother, Elizabeth Querini, came from an important family in Venice. Alvise was the oldest of three sons.

When he was very young, Alvise started working as a merchant, sailing on Venetian ships in the Mediterranean Sea. From 1442 to 1448, he traveled to places like the Barbary Coast and Crete, helping his cousin with trade. In 1451, he became an officer on a ship going to Alexandria, Egypt. The next year, he worked on a ship going to Flanders (modern-day Belgium).

When he returned, his family was in trouble. His father had been involved in a scandal and was forced to leave Venice. His mother's relatives took over their family's property. This made it hard for Alvise to have a good career in Venice. This challenge probably made him want to explore and achieve great things to restore his family's name and wealth.

Journeys to Africa

In August 1454, when Alvise was 22, he and his brother Antonio sailed on a Venetian merchant ship heading to Flanders. On their way, bad weather forced their ship to stop near Cape St. Vincent in Portugal.

While they waited, Prince Henry the Navigator, who lived nearby, sent his agents to talk to the Venetian merchants. They wanted to discuss trading sugar and other goods from the Prince's island of Madeira. When Alvise heard about Prince Henry's recent discoveries in Africa, he became very excited. He immediately asked Prince Henry if he could join an expedition. Prince Henry hired him right away.

First Journey (1455)

Alvise Cadamosto began his first journey on March 22, 1455. He sailed on a small ship called a caravel, provided by Prince Henry. He first went to Porto Santo and Madeira, then sailed through the Canary Islands, stopping at La Gomera, El Hierro, and La Palma. After that, he reached the African coast near Cape Blanc.

Cadamosto sailed down the West African coast to the mouth of the Senegal River. He called it the "Rio do Senega," which was the first time that name was recorded. He didn't stop there but continued south to a trading spot he called "Palma di Budomel." This place was already used by Portuguese traders. Cadamosto noted that trade between the Portuguese and the Wolof people of Senegal had started around 1450.

Cadamosto wanted to trade horses from Europe for people who were forced to work. Horses were very valuable on the Senegalese coast, and one horse could be traded for many people. Cadamosto sold seven horses and some wool for about 100 people.

While he was there, the local ruler, called the Damel of Cayor (whom he called "Budomel"), came to meet him. The Damel invited Cadamosto to visit his village inland. Cadamosto stayed for almost a month, hosted by the prince Bisboror. He learned a lot about the local country and its customs.

After his trade in Cayor was finished, Cadamosto decided to keep exploring further south. He wanted to find new lands, especially a mysterious "kingdom called Gambra," where Prince Henry believed there was a lot of gold. Near Cape Vert, in June 1455, Cadamosto met two other Portuguese ships. One was led by Antoniotto Usodimare, another captain working for Prince Henry. They decided to explore together.

After a short stop at some islands, Cadamosto, Usodimare, and the other captain sailed south. They reached the Sine-Saloum delta, where the Serer people lived. Cadamosto named the Saloum River the "Rio di Barbacini." They tried to land there, but the local Serer people killed their interpreter, so they quickly left.

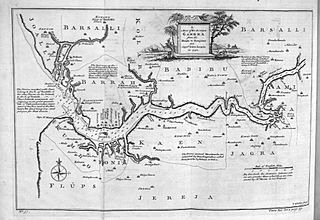

Continuing south, Cadamosto and Usodimare finally found the mouth of the Gambia River in late June or early July 1455. They tried to sail up the river, but the Mandinka people living there were very hostile. They were attacked by many canoes and barely escaped. Cadamosto's interpreters said the Mandinka believed the Portuguese were cannibals who wanted to buy people to eat. Because his crew was scared and he wanted to keep his cargo safe, Cadamosto decided to turn back. He did not give details about his return trip to Portugal.

At the mouth of the Gambia, Cadamosto noticed that the North Star was almost out of sight. He also drew a rough sketch of a bright group of stars to the south, which is believed to be the first drawing of the Southern Cross constellation by a European.

The ships were back in Portugal before the end of 1455. Antoniotto Usodimare wrote a letter in December 1455 to his friends in Genoa, telling them about his journey.

Second Journey (1456)

Cadamosto set sail again from Lagos, Portugal, in May 1456. This time, he was with Antoniotto Usodimare and another Portuguese captain. The three ships did not stop for trade. They planned to sail directly to the Gambia River, probably following Prince Henry's orders.

Near the Cape Vert peninsula, a storm forced the fleet to sail west for two days and three nights, about 300 miles. They unexpectedly found a group of islands that had not been discovered yet: the Cape Verde Islands. Cadamosto, Usodimare, and the unnamed captain explored several of these uninhabited islands. They thought there were four islands, but Cadamosto later noted that other explorers found ten. They first anchored at an island they named "Buona Vista" (Boa Vista), then went to a larger island they called "San Jacobo" (Santiago). Since the islands seemed uninteresting, they continued their journey.

(Note: While Cadamosto claimed to discover the Cape Verde islands, another explorer named Diogo Gomes said he discovered them in 1462.)

Cadamosto, Usodimare, and the Portuguese captain entered the Gambia River again. This time, there was no opposition. They sailed about 15 kilometers upriver and anchored briefly at a river island they named "Santo Andrea." They buried a crew member named Andrea there. This island is now believed to be Dog Island.

The three ships continued carefully upriver, watched by native Mandinka canoes. But this time, there were no attacks. Eventually, one of their interpreters managed to get some of the native people to come aboard the Portuguese ships, and they made peaceful contact. The natives said they were subjects of King Forosangoli, who ruled the southern bank of the Gambia. They also said that he and most other Mandinka kings along the river were vassals of the Emperor of Mali. Some of the local kings wanted to meet the Portuguese.

Following their instructions, Cadamosto sailed about 90 kilometers up the Gambia River. He reached the home of a Mandinka king he called "Battimansa," which means "king of the Batti" (probably Badibu, on the north side of the river). They were welcomed, but they were disappointed because they didn't find the large amounts of gold they expected. They traded some small items with the locals, especially musk, which was valuable for perfumes in Europe. They even got live civet cats.

Cadamosto also mentioned meeting another lord named Guumimensa, whose land was closer to the river's mouth. This was probably the powerful Niumimansa, king of the Niumi-Banta of the Barra region, who had often caused trouble for Portuguese explorers. However, Cadamosto reported that their relations went smoothly.

Cadamosto and his companions stayed in Badibu for 11 days before leaving. They did not reach the important trading center of Cantor, which was still further upriver. But Cadamosto and his crew did get sick with malaria. This sickness probably made Cadamosto cut short his stay and leave the Gambia River, heading back to the ocean, where the fevers seemed to lessen.

Determined to keep exploring the West African coast, Cadamosto's group sailed south. They passed Cape St. Mary and carefully navigated around the dangerous rocks near Bald Cape. They reported seeing a couple of rivers along the way. A few days later, Cadamosto and his companions discovered the mouth of the Casamance River. They named the river after the local lord, Casamansa, king of Kasa. They sent small boats to land to make contact, but they were told the king was away. So, Cadamosto did not stay long and decided to continue.

Sailing south, the fleet reached a red headland they named "Capo Rosso" (Cape Roxo), which is now the border between Senegal and Guinea-Bissau. Cadamosto mentioned two large rivers beyond Cape Roxo: Santa Anna and San Dominico. One is likely the Cacheu River, and the other is probably a branch of the Mansôa River.

A day later, Cadamosto discovered a very large river, which they named "Rio Grande" (the Geba River). They anchored near the southern bank of its wide mouth. Some native canoes approached them, but Cadamosto's interpreters could not understand their language, so they couldn't communicate. After a couple of days, they sailed to some of the many islands in the sea (the Bissagos Islands), but they also found it impossible to talk with the people there.

Because of the language barrier, they saw no reason to go further. Cadamosto, Usodimare, and the unnamed Portuguese captain sailed back to Portugal.

What They Achieved

Before Alvise Cadamosto, Portuguese explorers had not gone much beyond the Sine-Saloum delta. The furthest any explorer had gone was Álvaro Fernandes in 1446, who might have reached Cape Roxo, but no one followed up on that. Expeditions below Cape Vert were mostly stopped by Prince Henry. The main problem for the Portuguese was the hostility of the Niumi-Bato and Niumi-Banta people, led by King Niumimansa. Cadamosto faced this hostility on his first trip in 1455.

However, on his second trip in 1456, the opposition disappeared for some reason. Cadamosto became the first European (along with Antoniotto Usodimare and their companions) to sail up the Gambia River. It's not clear why the attitude changed.

Once they opened the Gambia River, Cadamosto and Usodimare made the next big step in Prince Henry's discoveries in Africa. They found the Cape Verde islands, the Casamance River, Cape Roxo, the Cacheu River, and finally the Geba River and the Bissagos Islands. The length of the coast they discovered in 1456 was the biggest leap in Portuguese discoveries since 1446. Other explorers, like Diogo Gomes, would later cover much of the same coast. Cadamosto's furthest point was only surpassed by Pedro de Sintra in 1461–62.

Back to Venice

After his return in 1456, Cadamosto lived in Lagos, Portugal, for many years. This suggests he continued to be involved in trade with West Africa. It's not known if Cadamosto himself made any more trips down the African coast. Cadamosto stated that there were no other important exploratory voyages after 1456 until Pedro de Sintra's expedition in 1462. Cadamosto learned about that expedition from Sintra's clerk when he returned.

Prince Henry the Navigator, Cadamosto's patron, died in November 1460. The control over African trade then went back to the Portuguese crown, and trade operations moved from Lagos to Lisbon. Cadamosto probably felt there was no future for him in Portugal, so he left and returned to Venice in February 1463.

Cadamosto is believed to have brought notes, logs, and maps with him. He used these to write his famous book, Navigationi, around the mid-1460s. In Navigazioni, he praised the Portuguese discoveries and Prince Henry. He gave detailed accounts of three expeditions: his own voyages in 1455 and 1456, and Pedro de Sintra's voyage in 1462. He likely gave much of his original material to the Venetian mapmaker Grazioso Benincasa, who then created an atlas in 1468 that showed the West African coast very accurately.

Cadamosto probably wrote Navigationi to show his achievements and help his family's reputation. When he returned, he managed to get back some of his family's property from his relatives. A few years later, he married Elisabetta di Giorgio Venier, a wealthy noblewoman. She was not healthy and died without having children. Cadamosto went back to trading, with business interests in Spain, Egypt, Syria, and England. With his wealth and connections restored, he also built a career in diplomacy and government for the Republic of Venice. He served in different roles and was sent on diplomatic missions. After a battle in 1470, Cadamosto was put in charge of planning how to defend Albania against the Ottoman Empire.

In 1481, Alvise Cadamosto was chosen to be the captain of the Venetian fleet going to Alexandria, ending his naval career on the same type of ships where he started. He died in 1483 while on a diplomatic mission in Polesine. (Some accounts say he died as early as 1477 or as late as 1488.)

For historians studying the Portuguese discoveries under Prince Henry the Navigator, Alvise Cadamosto's book, Navigazioni, is an extremely valuable document. Cadamosto's accounts, along with a chronicle by Gomes Eanes de Zurara and the memoirs of Diogo Gomes, are almost all that remains of the written records from that time. In fact, until another book was published in 1552, Cadamosto's Navigazioni was the only published work in Europe about the Portuguese discoveries. Cadamosto highlighted Prince Henry's important role, which helped create the image of the "Navigator Prince" for future generations. Historians praise Cadamosto's book for being reliable and detailed, giving a clearer picture of how Prince Henry's expeditions worked.

Cadamosto's accounts are also very important for historians of Africa. They provide the first detailed written descriptions of the Senegambia region. Cadamosto summarized what Europeans knew about West Africa at the time. He described the Mali Empire and the trans-Saharan trade. He explained how Berber caravans carried salt from desert areas to trading cities like Timbuktu.

He also explained how gold from Mali traveled in three directions: one part went east to Egypt, another went through Timbuktu north to Tunisia, and a third part, also through Timbuktu, went west to Ouadane, heading for Morocco. Some of this gold was then sent to the Portuguese trading post at Arguin.

Cadamosto was the first known person to call the Senegal River by its modern name, "Rio di Senega." He also thought the Senegal was probably the "Niger" river mentioned by ancient geographers. He repeated the old mistake of thinking that the Senegal River and the actual Niger River were connected, forming one large east-west river. He also shared the legend that it was believed to be a branch of the Biblical Gihon river, which flowed from the Garden of Eden through the lands of Aethiopia.

Cadamosto described the Wolof Empire, noting that it was bordered by the Fula and Toucouleur people to the east and the Mandinka states of the Gambia River to the south. Cadamosto gave many details about the politics, society, and culture of the Wolof states. He provided a very detailed eyewitness description of the Cayor village where he stayed in 1455, including the ruler's court, the people, their customs, economy, local animals, and plants. His descriptions show his great curiosity. He wrote about court customs, houses, the use of cowrie shells as money, food and drink, local markets, farming, palm wine production, weapons, dances, and music. He also described how people reacted to European items like clothes, ships, cannons, and bagpipes. Cadamosto's writing shows an honest curiosity and a lack of prejudice, which was surprising for a European of that time.

He also tried to give a detailed account of the Mandinka people of the Gambia River, noting their abundant cotton (which was rare in Wolof areas). However, his account was not as complete because he didn't explore much away from his boats there. He was amazed by the extraordinary wildlife, which was much more plentiful around the Gambia. He saw hippopotamuses (which he called "horse fish") and African elephants. He even tasted elephant meat and brought a salted piece back to Portugal for Prince Henry. A preserved elephant's foot was sent to Henry's sister, Isabella.

Book Editions

Alvise Cadamosto's accounts were first published in Italian in 1507 in a famous collection called Paesi novamente retrovati. It was quickly translated into Latin (1508), German (1508), and French (1515). The Italian version was reprinted in the well-known Ramusio collection in 1550. Although his book was reprinted and widely shared in other countries, a Portuguese translation did not appear until 1812.

For a long time, Cadamosto was also thought to be the author of the Portolano del mare, a book with sailing directions for the Mediterranean Sea coasts. However, modern historians generally believe Cadamosto did not write this book.

See also

In Spanish: Alvise Cadamosto para niños

In Spanish: Alvise Cadamosto para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |