Ānanda facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Venerable, the Elder (Thera) Ānanda |

|

|---|---|

Head of Ānanda, once part of a limestone sculpture from the northern Xiangtangshan Caves. Northern Qi dynasty, 550–577 CE.

|

|

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Known for | Being an attendant of the Buddha (aggupaṭṭhāyaka); powers of memory; compassion to women |

| Other names | Videhamuni; Dhamma-bhaṇḍāgārika ('Treasurer of the Dhamma') |

| Personal | |

| Born | 5th–4th century BCE Kapilavatthu |

| Died | 20 years after the Buddha's death On the river Rohīni near Vesālī, or the Ganges |

| Parents | King Śuklodana or King Amitodana; Queen Mrgī (Sanskrit traditions) |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | Patriarch of the Dharma (Sanskrit traditions) |

| Consecration | Mahākassapa |

| Predecessor | Mahākassapa |

| Successor | Majjhantika or Sāṇavāsī |

| Religious career | |

| Teacher | The Buddha; Puṇṇa Mantānīputta |

| Students | Majjhantika; Sāṇavāsī, etc. |

| Initiation | 20th (Mūlasarvāstivāda) or 2nd (other traditions) year of the Buddha's ministry Nigrodhārāma or Anupiya, Malla by Daśabāla Kāśyapa or Belaṭṭhasīsa |

Ānanda (Pali and Sanskrit: आनन्द; 5th–4th century BCE) was a very important helper and one of the main students of the Buddha. Among all the Buddha's students, Ānanda was known for having the best memory. Many of the early Buddhist teachings, called suttas, are believed to be his memories of what the Buddha taught. Because of this, he is known as the Treasurer of the Dhamma. Dhamma means the Buddha's teachings.

In early Buddhist writings, Ānanda was the Buddha's first cousin. He became a monk and was taught by Puṇṇa Mantānīputta. Twenty years into the Buddha's work, Ānanda became the Buddha's personal helper. He did his job with great care and was a link between the Buddha and ordinary people, as well as the group of monks and nuns (the saṅgha). He stayed with the Buddha for the rest of his life, helping him as an assistant, secretary, and spokesperson.

Ānanda played a big part in starting the order of bhikkhunīs (female monks or nuns). He asked the Buddha to allow his foster-mother, Mahāpajāpati Gotamī, to become a nun. Ānanda also stayed with the Buddha during his last year. He heard many important lessons the Buddha shared before he passed away. This included the idea that Buddhists should rely on the Buddha's teachings, not on a new leader. Ānanda was very sad when the Buddha died.

Soon after the Buddha's death, the First Buddhist Council was held. This was a big meeting where monks gathered to remember and agree on the Buddha's teachings. Ānanda became enlightened just before the council began, which was a requirement to join. He played a key role by remembering and reciting many of the Buddha's talks. However, during this meeting, he was also criticized by Mahākassapa and other monks. They felt he made some mistakes, like allowing women to become nuns. Ānanda continued to teach until he died, passing on his wisdom to students like Sāṇavāsī and Majjhantika. These students later became important leaders in future Buddhist councils. Ānanda died 20 years after the Buddha. Monuments called stūpas were built where he passed away.

Ānanda is one of the most loved figures in Buddhism. He was known for his amazing memory, knowledge, and kindness. The Buddha often praised him for these qualities. He was a contrast to the Buddha because he still had some worldly attachments and was not yet fully enlightened. In some Buddhist traditions, Ānanda is seen as a spiritual leader who received teachings from Mahākassapa and passed them on to his own students. Nuns have honored Ānanda for a long time because of his help in creating their order. Famous artists like Richard Wagner and Rabindranath Tagore were inspired by stories about Ānanda in their works.

Contents

What Does the Name Ānanda Mean?

The name ānanda (आनन्द) means 'bliss' or 'joy' in the ancient languages of Pāli and Sanskrit. Some old Buddhist stories say that when Ānanda was born, his family was very happy, which is why he got this name. Other stories say he was born on the same day the Buddha became enlightened. This brought great joy to the city, leading to his name.

Stories About Ānanda's Life

His Past Lives

Buddhist texts tell us that in a past life, Ānanda wished to become a Buddha's helper. He made this wish many, many years ago, during the time of a previous Buddha named Padumuttara. He met Padumuttara Buddha's helper and wanted to be like him. After doing many good deeds, he told Padumuttara Buddha his wish. The Buddha confirmed that his wish would come true in a future life. After many rebirths and good actions, he was born as Ānanda during the time of the current Buddha Gotama.

Ānanda's Early Life

Ānanda was born around the same time as the Buddha, in the 5th or 4th century BCE. He was the Buddha's first cousin. His father was the brother of Suddhodana, the Buddha's father. Some texts say his father was Amitodana, while others say Śuklodana. His mother's name was Mṛgī. Some stories say Ānanda was born on the same day as Prince Siddhattha (the Buddha's name before enlightenment). Other stories say he was born when the Buddha became enlightened, making him much younger than the Buddha. This idea is supported by parts of early texts where the Buddha talks to a younger Ānanda about getting old.

Ānanda became a monk early in the Buddha's work, during the Buddha's visit to Kapilavatthu. He was ordained by the Buddha himself, along with many other princes. Some stories say his father wanted more people from their noble family to become monks. So, Ānanda asked his brother Devadatta to stay home so he could join the monks. Other stories say Ānanda became a monk much later, about 20 years into the Buddha's work.

Ānanda's first teachers were Belaṭṭhasīsa and Puṇṇa Mantānīputta. Puṇṇa's teachings helped Ānanda reach an important stage on the path to enlightenment. Ānanda was very grateful to Puṇṇa. Another important person in Ānanda's life was Sāriputta, one of the Buddha's main students. Sāriputta often taught Ānanda about Buddhist ideas. They were good friends and shared things with each other.

Helping the Buddha

For the first 20 years of his teaching, the Buddha had different helpers. But when he was 55, he decided he needed a permanent helper. His previous helpers hadn't done a very good job. Many of the Buddha's top students offered to help, but the Buddha didn't choose them. Ānanda stayed quiet. When asked why, he said the Buddha would know best. The Buddha then chose Ānanda.

Ānanda agreed to be the helper, but only if he didn't get any special gifts from the Buddha. He didn't want people to think he was helping for selfish reasons. He also asked for a few things: to accept invitations for the Buddha, to ask the Buddha questions about his teachings, and to repeat any teachings the Buddha gave when Ānanda wasn't there. These requests would help people trust Ānanda and show that the Buddha supported him.

The Buddha agreed, and Ānanda became his helper for 25 years. He took care of the Buddha's daily needs, like bringing water and cleaning his room. He was very careful and dedicated, even guarding the Buddha's room at night. Ānanda often asked questions in the Buddha's talks, which helped everyone understand better. Their relationship was warm and trusting. When the Buddha got sick, Ānanda also felt unwell. As the Buddha got older, Ānanda continued to care for him with great devotion.

Ānanda sometimes put his own life at risk for the Buddha. Once, a rebellious monk named Devadatta tried to harm the Buddha by releasing a wild elephant. Ānanda bravely stepped in front of the Buddha to protect him. Even when the Buddha told him to move, Ānanda refused. The Buddha then used his special powers to move Ānanda aside and calm the elephant with kindness.

Ānanda often acted as a messenger and secretary. He passed messages from the Buddha, shared news, and advised people who wanted to give gifts to the monks. Once, the Buddha's foster-mother, Mahāpajāpatī, wanted to give the Buddha robes. The Buddha first said she should give them to the whole community. But Ānanda stepped in, reminding the Buddha how Mahāpajāpatī had cared for him as a child. The Buddha then accepted the robes, but also taught Ānanda that good deeds should be done for the action itself, not for the person.

The Buddha sometimes asked Ānanda to teach in his place and often praised his lessons. Ānanda taught important people, like queens and royal officials. Once, he taught some of King Udena's concubines. They were so impressed they gave him 500 robes. The King criticized Ānanda for being greedy, but Ānanda explained how the robes were used and recycled by the monks. This made the king offer another 500 robes.

Ānanda also helped the city of Vesālī. The Buddha taught him a special text called the Ratana Sutta. Ānanda then recited it in Vesālī, which helped the city recover from illness and drought. In another famous story, Ānanda said that spiritual friendship is half of the holy life. The Buddha corrected him, saying it is the entire holy life. In short, Ānanda was a vital assistant, messenger, and teacher, helping the Buddha in many ways and learning his teachings deeply.

Avoiding Temptations

Ānanda was known for being very handsome. One story says a nun became fond of him and pretended to be sick so Ānanda would visit her. When she realized her mistake, she confessed to him. Other stories tell of a woman named Prakṛti who fell in love with Ānanda. Her mother used a magic spell to trick him into her house. But Ānanda realized what was happening and called for the Buddha's help. The Buddha then taught Prakṛti to think about the human body's less attractive parts. Eventually, Prakṛti became a nun, giving up her attachment to Ānanda. In some versions, the Buddha sent Mañjuśrī to help Ānanda, using special chants to break the magic.

Starting the Nun's Order

Ānanda played a very important role in allowing women to join the early Buddhist monastic community. About 15 years after the Buddha became enlightened, his foster mother, Mahāpajāpatī, asked to be ordained as the first Buddhist nun. The Buddha first said no. Five years later, Mahāpajāpatī asked again, this time with other women, including the Buddha's former wife, Yasodharā. They had walked a long distance and looked very tired. Ānanda felt sorry for them.

Ānanda then asked the Buddha if women could also become enlightened. The Buddha agreed that they could. But he still didn't allow the women to be ordained. Ānanda then reminded the Buddha how Mahāpajāpatī had cared for him after his birth mother died. He also mentioned that previous Buddhas had allowed nuns. Finally, the Buddha allowed the women to be ordained, which started the bhikkhunī (nun) order. Ānanda helped Mahāpajāpati get ordained by accepting a set of rules given by the Buddha. These rules, called the garudhamma, described how the nuns' community would relate to the monks' community.

Many scholars believe the Buddha was hesitant to allow women to be ordained, and Ānanda successfully convinced him. However, some think the Buddha's refusal was a test of their determination. Regardless, the Buddha told Ānanda that because women joined, his teachings might not last as long. At that time, the Buddhist community was mainly wandering male monks. Allowing women might have caused problems or temptations. The garudhamma rules were meant to prevent these issues.

Ānanda's role in creating the nun's order made him very popular with the nuns. He often taught them and encouraged women to become ordained. When the monk Mahākassapa criticized Ānanda, several nuns tried to defend him.

The Buddha's Last Days

Even though Ānanda had been with the Buddha for so long, he had not yet become fully enlightened. Another monk, Udāyī, made fun of Ānanda for this. But the Buddha told Udāyī that Ānanda would definitely become enlightened in this life.

The Pāli text Mahā-parinibbāna Sutta describes the Buddha's last journey with Ānanda. The Buddha was 80 years old and became very sick. Ānanda was worried. He thought the Buddha wanted to give final instructions. But the Buddha said he had already taught everything openly, like a teacher with "no closed fist." He also told Ānanda that the monks should not rely too much on a leader, not even himself. He famously said that his teachings and discipline should be their refuge, and they should be their own refuge, without relying on anyone else.

The same text says the Buddha hinted many times that he could live longer using special powers, but Ānanda was distracted and didn't ask him to. Later, when Ānanda did ask, the Buddha said it was too late. He had already decided to die in three months. When Ānanda heard this, he cried. The Buddha comforted him, saying Ānanda had been a great helper and would soon become enlightened if he tried hard. He reminded Ānanda that all things change and everyone must die.

In the Buddha's final days, he traveled to Kusinārā. He asked Ānanda to prepare a place for him to lie down between two sal trees. The Buddha then asked Ānanda to invite the Malla clan to pay their last respects. Ānanda asked what should be done with the Buddha's body after he died. The Buddha gave detailed instructions for cremation.

Before the Buddha died, Ānanda suggested moving to a bigger city. But the Buddha said Kusinārā was once a great capital. Ānanda then asked who would be the next teacher. The Buddha replied that his teachings and discipline would be the teacher. This meant that decisions should be made by agreement among the monks, and that the Buddhist texts would be the authority after he was gone.

In his final moments, the Buddha asked if anyone had any questions. No one did. Ānanda expressed joy that all the disciples present had no doubts. But the Buddha pointed out that Ānanda spoke from faith, not from deep understanding. He also said that even the "least advanced" monk present had reached an early stage of enlightenment, referring to Ānanda to encourage him. After the Buddha's death, Ānanda recited verses, showing how deeply moved he was.

Ānanda later went to the Buddha's old living quarters. He went through the same routines he used to do when the Buddha was alive, like preparing water and cleaning. He even talked to the empty room as if the Buddha was still there. Old stories say he did this out of deep devotion, but also because he was "not yet free from worldly feelings."

The First Buddhist Council

Becoming Enlightened

The First Buddhist Council was held in Rājagaha. After the Buddha died, the head monk Mahākassapa called for Ānanda to recite the teachings he had heard. Only enlightened students were allowed to attend the council. Ānanda had not yet reached enlightenment, unlike the other 499 enlightened monks. Mahākassapa did not allow Ānanda to join at first.

Ānanda felt embarrassed, but he was determined to become enlightened before the council started. He remembered the Buddha's words to be his own refuge. He tried very hard to reach enlightenment the night before the meeting. After a while, he took a break and lay down to rest. It was at that moment, halfway between standing and lying down, that he became enlightened! So, Ānanda is known as the student who reached awakening "in none of the four traditional poses." The next morning, to prove his enlightenment, Ānanda used special powers to appear at his seat in the council.

Today, the story of Ānanda's struggle is still told to teach about meditation: don't give up, but also don't be too strict with yourself.

Reciting the Teachings

The First Council began with Ānanda. He was asked to recite the Buddha's talks to make sure they were correct. Mahākassapa asked Ānanda where, when, and to whom each teaching was given. The monks agreed that Ānanda's memories were accurate. This is how the collection of talks, called the Sutta Piṭaka, was put together. Ānanda played a vital role, remembering 84,000 teaching topics. Many early Buddhist talks begin with "Thus have I heard" (Evaṃ me sutaṃ). These are Ānanda's words, showing that he heard the teachings directly from the Buddha.

Criticisms During the Council

During the council, Ānanda was criticized by some monks. One reason was for helping women join the monastic order. He was also criticized for forgetting to ask the Buddha to clarify some rules, for stepping on the Buddha's robe, for letting women cry on the Buddha's body after his death, and for not asking the Buddha to live longer.

Ānanda didn't see these as big mistakes, but he agreed to formally apologize to keep peace among the monks. About allowing women to be ordained, Ānanda explained he did it because Mahāpajāpati was the Buddha's foster-mother and had cared for him. About not asking the Buddha to live longer, many stories say he was distracted by Māra (the Buddhist personification of evil).

Some scholars believe these criticisms show disagreements between different early Buddhist groups. Groups that focused on the Buddha's talks might have favored Ānanda more, while groups that focused on monastic rules might have been harder on him.

Ānanda's Character and Role

"He served the Buddha following him everywhere like a shadow, bringing him tooth wood and water, washing his feet, rubbing his body, cleaning his cell and fulfilling all his duties with the greatest care. By day he was at hand forestalling the slightest wish of the Buddha. At night, staff and torch in hand, he went nine times round the Buddha's cell and never put them down lest he would fall asleep and fail to answer a call to the Buddha."

Ānanda was one of the Buddha's most important students. He was known for his good behavior, care for others, amazing memory, vast knowledge, and strong determination. The Buddha praised him just before his death, calling him kind, unselfish, popular, and thoughtful. Ānanda was kind to ordinary people, a quality he learned from the Buddha. Both monks and laypeople were happy to see and hear Ānanda teach. He was also good at organizing things, helping the Buddha with many tasks. Ānanda not only helped the Buddha personally but also supported the growing Buddhist community.

Because he could remember so many of the Buddha's teachings, he was known as "having heard much." His exceptional memory was key to preserving the Buddha's words. He also taught other students how to memorize Buddhist ideas. This is why he was called the "Treasurer of the Dhamma" (the Buddha's teachings). Ānanda was like the living memory of the Buddha, without whom many teachings might have been lost.

As the Buddha's cousin, Ānanda was brave enough to ask direct questions. For example, after another religious leader died and his community had conflicts, Ānanda asked the Buddha how to prevent such problems after his own death. However, some scholars note that while Ānanda remembered teachings perfectly, he sometimes didn't reflect on them deeply. Other students sometimes told him to spend less time talking to people and more time on his own meditation. He was less experienced in deep meditation than other top students. So, how people judge Ānanda depends on whether they look at his skills as a helper or his personal spiritual growth.

In Buddhist stories, Ānanda often served as a contrast to the Buddha. He was not yet enlightened and made mistakes, which made him relatable to ordinary people. Through Ānanda, the Buddha could explain his teachings more easily. The Buddha was like a father and teacher to Ānanda, strict but caring. Ānanda loved the Buddha very much and was willing to risk his life for him. He was deeply sad when the Buddha and his close friend Sāriputta died.

Ānanda's faith was often in the Buddha as a person, rather than just in his teachings. This personal attachment is seen as one reason for his slower spiritual progress. His weaknesses included sometimes being slow to understand and lacking full awareness. For example, Mahākassapa once criticized Ānanda for traveling with many young, untrained monks who had a bad reputation. Ānanda's spiritual growth was slower than other students because of his worldly attachments and his strong attachment to the Buddha as a person. These were linked to his work as a go-between for the Buddha and the community.

Passing on the Teachings

After the Buddha's death, some sources say Ānanda mostly stayed in West India, teaching his students. Others say he stayed in a monastery. Several of Ānanda's students became famous. According to later texts, the Buddha told Ānanda that his student Majjhantika would travel to Kashmir to spread the Buddha's teachings there. Another future student of Ānanda, Sāṇavāsī, was predicted to make many gifts to the monks. After this, Ānanda convinced Sāṇavāsī to become a monk and his student. Ānanda told Sāṇavāsī that he had given many material gifts but not "the gift of the Dhamma" (teachings). When asked to explain, Ānanda said Sāṇavāsī would give the gift of Dhamma by becoming a monk, which convinced him.

Death and Relics

Early Buddhist texts don't give a date for Ānanda's death. However, a Chinese monk named Faxian (who lived from 337 to 422 CE) wrote that Ānanda lived to be 120 years old. Some scholars believe he lived to be 75-85 years old, dying about 20 years after the Buddha.

Ānanda taught until the end of his life. One story says he heard a young monk recite a verse incorrectly and corrected him. The monk's teacher said, "Ānanda has grown old and his memory is not good." This made Ānanda decide to pass away. He gave his spiritual leadership to his student Sāṇavāsī and went to the Ganges River.

Other stories say that when Ānanda was about to die, he went to the Rohīni River. He was followed by King Ajātasattu, who wanted to see his death and get his remains as relics. On the other side of the river, a group of people called the Licchavis also waited for the same reason. Ānanda realized that dying on either side of the river could make one group angry. So, using his special powers, he rose into the air and meditated. His body then went up in fire, and his relics landed on both sides of the river. This way, Ānanda pleased everyone. In some versions, he died on a boat in the middle of the river. His remains were divided in two, as he wished.

King Ajātasattu is said to have built a stūpa (monument) over Ānanda's relics at the Rohīni River. The Licchavis also built a stūpa on their side. Later, Chinese travelers visited these stūpas. King Aśoka (3rd century BCE) is said to have made the most generous offerings to Ānanda's stūpa. He explained that he did this because Ānanda remembered all of the Buddha's teachings.

"Who in the Norm is widely versed,

- And bears its doctrines in his heart—

- Of the great Master's treasure Ward—

- An eye was he for all the world,

- Ānanda, who is passed away."

Early Buddhist texts say Ānanda reached final Nirvana and would not be reborn. However, in the Mahāyāna Lotus Sūtra, it says Ānanda will become a Buddha in the future. He would achieve this more slowly than the current Buddha, but his enlightenment would be amazing and splendid because of his great learning and efforts.

Ānanda's Lasting Impact

Ānanda was a skilled speaker who often taught about self-awareness and meditation. Many Buddhist texts are believed to be his teachings. These include texts about meditation to reach Nirvana, living in the present moment, and the training of a Buddha's student. In one conversation after the Buddha's death, Ānanda explained that no new leader was appointed. Instead, the Buddhist community would rely on the Buddha's teachings and discipline as their guide.

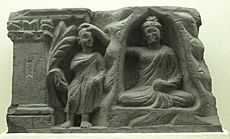

In East Asian Buddhism, Ānanda is considered one of the ten main students. In many Indian and East Asian texts, he is seen as the second spiritual leader in the line that passed down the Buddha's teachings. Mahākassapa was the first, and Majjhantika or Sāṇavāsī was the third. In Mahāyāna art, Ānanda is often shown next to the Buddha on the right, with Mahākassapa on the left.

Because Ānanda helped start the nun's community, nuns have honored him throughout history. Old writings show that nuns made offerings at monuments dedicated to Ānanda. In China and Japan, Buddhist texts encouraged women to follow special rules in honor of Ānanda. By the 13th century in Japan, some convents even held ceremonies for him.

Pāli texts say that Ānanda designed the Buddhist monk's robe. As Buddhism grew, people donated expensive cloth for robes. To make them less valuable for thieves, monks cut the cloth into small pieces. The Buddha asked Ānanda to design a robe from these pieces. Ānanda created a standard robe based on the patterns of rice fields, which are divided by earth banks.

Another tradition linked to Ānanda is paritta recitation (protective chanting). Buddhists believe that sprinkling water during paritta chanting started when Ānanda recited the Ratana Sutta in Vesālī and sprinkled water from his bowl. A third tradition sometimes linked to Ānanda is the use of Bodhi trees in Buddhism. A story says Ānanda planted a Bodhi tree as a symbol of the Buddha's enlightenment, so people could pay their respects. This tree became known as the Ānanda Bodhi Tree. Many Bodhi tree shrines in Southeast Asia were built following this example.

Ānanda in Art

Between 1856 and 1858, the composer Richard Wagner started writing an opera based on the story of Ānanda and Prakṛti. He only made a small sketch, but the idea inspired his later opera Parsifal. In Wagner's version, Prakṛti's mother's magic doesn't work on Ānanda. Prakṛti then asks the Buddha about her feelings for Ānanda. The Buddha says they can be together, but Prakṛti must agree to his conditions. She agrees, and the Buddha reveals he means something different: he asks Prakṛti to become a nun and live a celibate life, like a sister to Ānanda. At first, Prakṛti is sad, but after the Buddha explains it's due to her past actions (karma), she understands and happily becomes a nun. Wagner also criticized the caste system in his work.

The Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore also wrote a play about Ānanda and Prakṛti called Chandalika. This play explores spiritual conflict, social equality, and criticizes Indian society. In Tagore's play, Prakṛti falls in love with Ānanda after he shows her respect by accepting water from her. Her mother uses a spell to enchant Ānanda. But in this version, Prakṛti later regrets her actions and has the spell removed.

See Also

In Spanish: Ananda para niños

In Spanish: Ananda para niños