Bayou Corne sinkhole facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bayou Corne sinkhole |

|

|---|---|

Image of Bayou Corne taken from canoe

|

|

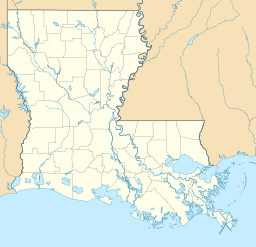

| Location | Assumption Parish, Louisiana |

| Coordinates | 30°0′40″N 91°8′35″W / 30.01111°N 91.14306°W |

| First flooded | August 3, 2012 |

| Surface area | 37 acres (15 ha) |

| Max. depth | at least 750 ft (230 m) |

The Bayou Corne sinkhole (which means "Bayou Corne sinkhole" in French) is a huge hole in the ground. It formed when an underground cavern, used for storing things, collapsed. This cavern was part of a salt dome and was operated by Texas Brine Company. The sinkhole is in Assumption Parish, Louisiana. It was first discovered on August 3, 2012. Because of the danger, about 350 people living nearby had to leave their homes. Experts say they might not be able to return for many years.

Contents

What Caused the Bayou Corne Sinkhole?

Understanding Salt Domes in Louisiana

Many areas in Louisiana, including places like Bayou Corne, are built on top of huge underground salt domes. These are giant deposits of salt that formed over millions of years. They were created when the North American continent was forming.

These salt domes can be very different in size and how deep they are. Some are as deep as 35,000 feet (over 6 miles) below the surface. Some are as big as Mount Everest! Because they are so deep, these domes are naturally under a lot of pressure.

How People Use Salt Domes

People have used the salt from these domes for hundreds of years. Salt mining has been happening in Louisiana since the early 1800s. Later, in the 1900s, the government started using these underground salt caverns. They used them as giant storage places for crude oil, which is a type of oil found underground.

When companies mine salt or store oil in these caverns, they need to be very careful. They must make sure the ground stays stable. If they don't, a disaster like the one at Lake Peigneur can happen.

The Napoleonville Dome and Oxy3 Cavern

The Napoleonville Dome is a large salt dome under Assumption Parish. It had 53 different caverns inside it. Six of these caverns were used by Texas Brine. One of them, called Oxy3, was owned by Occidental Petroleum. This cavern was more than a mile below the ground.

Oxy3 was less than 100 feet away from a nearby oil and gas storage area. This distance was considered unsafe, even though it wasn't against the law at the time. In 2010, Texas Brine asked for permission to make the Oxy3 cavern bigger. Tests showed that the cavern might not be strong enough to handle more pressure. However, the company believed it would be fine.

How the Sinkhole Grew Over Time

When the sinkhole first appeared, it was about 2.5 acres wide. By early 2014, it had grown much larger, reaching 26 acres. It continued to expand. Texas Brine is still in charge of managing the sinkhole. They have burned off a lot of gas that was escaping from it. This was an attempt to reduce the amount of gas coming out.

The Sinkhole's "Burps"

Areas near Bayou Corne have also shown bubbling on the surface. However, scientists haven't officially linked these bubbles to the main sinkhole. Scientists don't know exactly when people will be able to return home. The decision depends a lot on how much methane gas is still escaping.

Surveys done in early 2014 showed that the sinkhole's growth was slowing down. It seemed to be becoming more stable. Besides the methane gas bubbling up, the sinkhole also tends to "burp" out debris. This is how it expands. First, the ground shakes a little. Then, the sinkhole throws out some dirt, oil, and other material. This makes space for more dirt and even trees to fall into the hole.

Impact on People and Nature

Residents and Legal Actions

The people who lived in Bayou Corne had to leave their homes. By March 2014, they had been evacuated for 19 months. Many of them got involved in legal battles with Texas Brine. From the start of the evacuation, Texas Brine sent checks to each resident. Some residents even received these checks without leaving town.

After nine months, the Governor of Louisiana said he would sue Texas Brine. He wanted them to offer to buy out the residents' homes. Texas Brine then offered to deal with the 350 affected residents. By March 2014, 65 people had accepted some form of buyout. Others chose to join a group lawsuit against Texas Brine. This lawsuit was planned to go to trial in 2014.

Environmental Concerns

The effects of the sinkhole on local plants and animals are still being studied. However, the sinkhole continues to damage nearby cypress trees. It swallows them as it expands. One reporter called the Bayou Corne incident "the biggest ongoing industrial disaster in the United States you haven't heard of."

In 2014, a group lawsuit led to a proposed settlement of $48.1 million. Some residents felt that the money set aside for legal fees was too high.

Company Lawsuits and Responsibility

In September 2014, Texas Brine asked for permission to put wastewater back into the sinkhole. They hoped this would help fix some of the damage. This idea caused a lot of debate among residents. They wondered if the company responsible for the damage should be allowed to do more work in an area already called "deeply contaminated."

In July 2015, Texas Brine started suing Occidental Petroleum. Texas Brine claimed that an oil well drilled by Occidental Petroleum in 1986 caused the cavern wall to break. This break, they said, led to the sinkhole. Texas Brine asked Occidental Petroleum for $100 million in damages.

In 2018, a judge ruled that three companies shared the blame. Texas Brine was 35% at fault. Occidental Chemical was 50% at fault. Vulcan was 15% at fault. Appeals to this ruling are expected to happen.