Catherine Gladstone facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Catherine Gladstone

|

|

|---|---|

Gladstone in 1883

|

|

| Born |

Catherine Glynne

6 January 1812 Flintshire, Wales

|

| Died | 14 June 1900 (aged 88) Flintshire, Wales

|

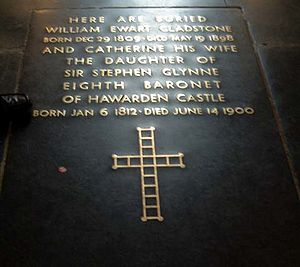

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 8, including William, Helen, Henry and Herbert |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Signature | |

Catherine Gladstone (born Catherine Glynne; 6 January 1812 – 14 June 1900) was a very important woman in British history. She was married to William Ewart Gladstone, who was the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom four times. Their marriage lasted for 59 years, from 1839 until her husband's death in 1898.

Her Early Life and Family

Catherine Glynne was born in Flintshire, Wales. Her father was Sir Stephen Glynne, 8th Baronet, who owned Hawarden Castle. Sadly, her father passed away when Catherine was only three years old. She and her sister, Mary, were then raised by their mother.

The Glynne sisters were very close. They were also known for their beauty. Both sisters got married on the same day at Hawarden Church. Their families often visited each other and went on holidays together. When Mary passed away in 1857, Catherine helped care for her sister's children.

Catherine's brother, Stephen, inherited the title of Baronet in 1815. When he died in 1874, the Glynne family title ended. The Hawarden Castle estates then went to Catherine and William's oldest son, William Henry. Because of her family connections, Catherine was related to many famous people in British politics.

Meeting William Gladstone

Catherine met William Gladstone through her brother. Her brother was a MP for Flintshire. People say Catherine and William met in 1834 in London. They were married on 25 July 1839.

After they married, Catherine and William lived at her family home, Hawarden Castle. They had eight children together. Some of their children included Herbert John and Henry Neville Gladstone. Catherine was buried next to her husband in Westminster Abbey after she passed away. Their daughter, Mary, used to call them "The Great People."

Her Kind and Busy Character

Catherine Gladstone was known for her unique and successful way of living. She was described as being "like a fresh breeze" wherever she went. A friend said she could quickly understand any discussion.

Unlike her very tidy husband, Catherine was known for being a bit messy. She often left her letters on the floor. She trusted that someone would eventually pick them up and mail them. Her drawers were also quite untidy. She didn't worry much about wearing fancy clothes. She once joked with her husband, "What a bore you would have been if you had married someone as tidy as you are."

Even though her own life was sometimes a bit disorganized, Catherine worked hard to help others. She helped start places like homes for people recovering from illness and orphanages. She gave a lot of her time and effort to many people. She was responsible for many helpful projects. She was able to do this with her creative ideas and the help of devoted friends.