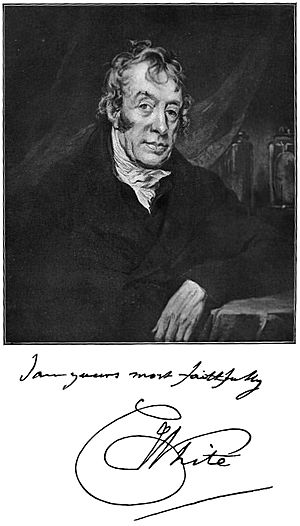

Charles White (physician) facts for kids

Charles White (born October 4, 1728 – died February 20, 1813) was an English doctor. He helped start two important hospitals in Manchester: the Manchester Royal Infirmary and St Mary's Hospital for Lying-in Women. He made big improvements in how doctors treated bones (orthopaedics), performed surgeries, and helped women during childbirth (obstetrics). He was also a founding member of the Portico Library and the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Charles White was born in Manchester, England, on October 4, 1728. He was the only son of Thomas White, who was also a surgeon and midwife. Charles started learning from his father around 1742, when he was just 14 years old. He was able to help with surgeries and deliveries even at that young age.

Later, in 1748, he moved to London to study medicine with a famous anatomist and obstetrician named William Hunter. After his training in London, he went to Edinburgh to study even more. He returned to Manchester in 1751 and joined his father's medical practice. After his father passed away, Charles continued the practice until he retired to his country home.

Medical Career and Innovations

Surgical Techniques

Charles White became known as a very skilled and creative surgeon.

- In 1760, he shared a paper with the Royal Society about how he successfully treated a broken arm by putting the bone ends back together.

- In 1762, he wrote another paper about using sponges to stop bleeding. Before this, doctors often used painful ligatures (tying off blood vessels). White showed that sponges were less painful and worked better, especially for bad cuts. He reported 13 cases where his method worked when others had failed.

- He also created a special way to fix dislocated shoulders. He used an iron ring in the ceiling with a pulley. He would attach bandages to the patient's arm and gently pull them up to help put the shoulder back in place. He said he never failed to fix a dislocated shoulder in 20 years!

- In 1768, he treated a 14-year-old boy with a bone infection in his arm. Instead of cutting off the arm, which was common then, White removed a small part of the infected bone. The boy recovered and could use his arm fully. This was a very advanced surgery for its time.

- He was also very good at removing bladder stones, a common and dangerous operation back then.

- White and his son Thomas gave some of the first anatomy lectures outside of London. They started teaching these lessons in Manchester in 1783.

Improving Childbirth Care

White is especially remembered for his work in helping women during pregnancy and childbirth. His most important book, A Treatise on the Management of Pregnant and Lying-in Women, was published in 1773. It was printed many times and translated into other languages.

In his book, he suggested big changes to how women were cared for.

- He described how delivery rooms were often crowded, hot, and stuffy with closed windows. Women were made to lie flat and covered with heavy blankets.

- White insisted on cool rooms with open windows. He also demanded very clean conditions. This included regular hand washing for doctors and midwives, clean bed sheets, towels, and instruments.

- He believed in isolating women who developed a fever to stop the spread of illness. After a sick woman left, he said the room should be thoroughly cleaned.

- He also encouraged women to get out of bed and move around soon after giving birth, usually within a day or two. This was very unusual at the time, as women were typically kept in bed for many days.

Puerperal fever, a serious infection after childbirth, was a common cause of death for women. White's practices greatly reduced this problem in his care. He believed that allowing fluids to drain naturally was important. He even designed a special chair to help with this. His methods were so successful that puerperal fever was almost eliminated from his hospital wards.

His ideas were far ahead of his time. For example, he advised waiting for a pause after the baby's head was delivered before helping with the shoulders. He also insisted on waiting until the umbilical cord stopped pulsing before cutting it. These practices are now known to be beneficial for the baby's health.

Manchester Royal Infirmary

When Charles White returned to Manchester in 1751, he worked hard to create a hospital. A wealthy local merchant, Joseph Bancroft, agreed to pay for everything if Dr. White would provide his medical services for free. In 1752, a house with 12 beds was opened as a hospital. Three years later, in 1755, the Manchester Public Infirmary opened in a new, bigger building. White worked as a surgeon there for 38 years.

St Mary's Hospital Manchester

In 1790, after a disagreement with the board of the Manchester Royal Infirmary, Charles White and his son Thomas, along with other doctors, left and founded the Lying-in Hospital at St Mary's. Charles White continued to work there for many years.

The Manchester Mummy

One interesting story about Charles White involves a woman named Hannah Beswick. Hannah was very afraid of being buried alive. After she died in 1758, she asked in her will that Dr. White keep her body above ground for 100 years. White had her body embalmed (preserved) and kept it in his museum, which had many other medical specimens.

After White died in 1813, Hannah's mummified body was given to the Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society. She became known as the "Manchester Mummy." Her body was displayed in the museum's entrance hall for many years. In 1867, the museum was moved to Manchester University. With permission from the Bishop of Manchester, Hannah Beswick was finally buried in 1868.

While this might seem strange today, preserving bodies for study was something other doctors did at the time.

Later Life and Family

In 1757, Charles White married Ann Bradshaw. They had eight children, four sons and four daughters. Sadly, all four of his sons passed away before him.

In 1803, White began to lose his eyesight, first in one eye, then in the other. By 1811, he was completely blind. He died at his home in Sale on February 20, 1813. He was survived by his daughters.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |