Dorothy Mae Taylor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Dorothy Mae DeLavallade Taylor

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Louisiana State Representative for District 20 (Orleans Parish) | |

| In office 1971–1980 |

|

| Preceded by | Ernest Nathan Morial |

| Member of the New Orleans City Council | |

| In office 1986–1994 |

|

| Succeeded by | Two at-large members: Peggy Wilson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 10, 1928 New Orleans, Louisiana, USA |

| Died | August 18, 2000 (aged 72) New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Johnny Taylor, Jr. (married 1948) |

| Children | Seven children |

| Parents | Charles H. and Mary Jackson DeLavallade |

| Residences | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Alma mater | Southern University |

| Occupation | Civil rights activist Government official |

Dorothy Mae DeLavallade Taylor (born August 10, 1928 – died August 18, 2000) was an important educator and politician from New Orleans. She made history as the first African-American woman to be elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives. From 1971 to 1980, she represented her hometown of New Orleans in the state legislature.

Before her political career, Dorothy Taylor worked as a teacher in the Head Start Program. This program helps young children get a good start in their education. She was also very active in the civil rights movement during the 1950s and 1960s. She fought to get more resources and better facilities for African Americans in New Orleans. Her work focused on important issues like health care, child care, and stopping unfair treatment based on race. She also worked to improve conditions in state prisons.

After her time in the legislature, she directed the Central City Neighborhood Health Clinic starting in 1980. She helped many African-American staff members become leaders. She also guided several people who later became important politicians in Louisiana. In 1984, Governor Edwin Edwards chose her to lead the state Department of Urban and Community Affairs. This made her the first African-American woman to hold a cabinet position in Louisiana.

Contents

Dorothy Taylor's Journey in Politics

Dorothy Taylor started her public service work in the Parent Teacher Association (PTA). She demanded that the Orleans Parish School Board provide equal supplies and funding for African-American children. She played a key role in ending segregation at the New Orleans Recreation Department. She also helped many people register to vote.

While working as a deputy clerk, Taylor won a special election in 1971. She took the place of Ernest Nathan Morial in the state House. Morial had become the first African-American juvenile court judge in New Orleans.

Becoming a State Representative

After being elected, Taylor felt a bit nervous about being the first African-American woman in the state House. She said she "prayed and prayed" and found her answer in church. She realized that she had a special purpose in life. In 1972, Louisiana State University recognized her as "Legislator of the Year."

Sidney Barthelemy, who later became mayor of New Orleans, remembered Taylor's dedication. He said she was deeply committed to making the justice system fair for everyone. She worked hard to ensure that all people, especially those in prison, were treated kindly. She believed that even people who were incarcerated deserved basic health care and a good quality of life. She felt that treating people with respect would help them act better when they returned to the community.

Leading the Central City Neighborhood Health Clinic

After leaving the state legislature in 1980, Taylor became the director of the Central City Neighborhood Health Clinic. This clinic was run by the Total Community Action Agency in New Orleans. She focused on helping other African-American leaders grow within these agencies.

Many people she mentored went on to hold political office. These included State Senator Henry Braden and Public Service Commissioner Irma Muse Dixon. State Representative Sherman Copelin also learned from her. Austin Badon was an intern in Taylor's City Hall office. He later became a state Representative himself.

A Historic Cabinet Position

In 1984, Governor Edwin Edwards appointed Taylor to lead the state Department of Urban and Community Affairs. This was a very important step. It made her the first African-American woman to hold a cabinet position in Louisiana's state government. In 1985, she received the "Humanitarian Award" for her community work.

Serving on the New Orleans City Council

In 1986, Dorothy Taylor was elected to the New Orleans City Council. She won one of the two citywide positions. She was the first African-American woman to be elected to this specific seat. She served on the council until 1994, when she reached her term-limits. In 1987, her fellow council members chose her to be the council president. Her time on the council happened at the same time as Mayor Barthelemy's term.

Fighting for Fairness in Mardi Gras

In 1992, Dorothy Mae Taylor wrote an important rule about Mardi Gras parades. She said that all Mardi Gras krewes (the groups that organize the parades) must stop discriminating. They had to allow anyone to join their organizations if they wanted to use city services for their parades.

The reaction to this rule was very strong. Some old krewes threatened to stop parading in New Orleans. Mrs. Taylor held public meetings. During these meetings, club members had to answer tough questions. It became clear that many old krewes were "all-male and all-white." They excluded not only Black people, but also women, gay people, Jewish people, and Italian people.

Some krewes, like Momus and Comus, decided to stop parading. They said they would not parade in New Orleans anymore. People started writing articles and making T-shirts that criticized Mrs. Taylor. They called her "The Grinch who Stole Mardi Gras." There was a lot of tension in the city.

Even years later, some people were still upset. But others, like Sidney Barthelemy, believed Mrs. Taylor was simply trying to protect everyone's rights. He said her goal was never to destroy Mardi Gras. She just wanted to make sure that certain groups didn't treat others unfairly.

Jay Banks, another community leader, explained that Mrs. Taylor believed that if krewes benefited from public money, they should be open to the public. He said that many important business deals happened in those private clubs. These deals often involved tax money, and most people didn't have a chance to be part of them. Mrs. Taylor wanted to make things fair for everyone.

Banks also said that Mrs. Taylor was brave. She didn't mind facing criticism if she believed she was doing the right thing. He felt that her actions actually made Mardi Gras "bigger and better" than it was before. Some krewes that stopped parading said they would go to other parishes, but many never did. The ones that stayed became more open and welcoming.

Dorothy Taylor passed away in New Orleans in 2000, shortly after her 72nd birthday. Her legacy is remembered as someone who fought for what was right and helped make her community more fair for everyone.

Images for kids

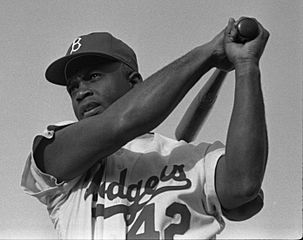

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |