Electromagnetic spectrum facts for kids

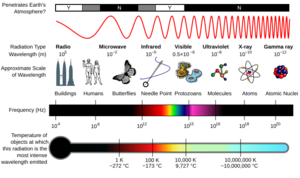

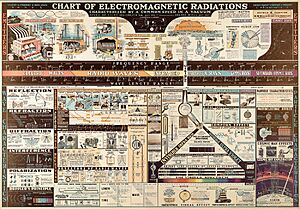

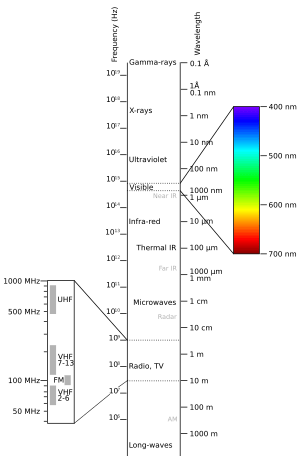

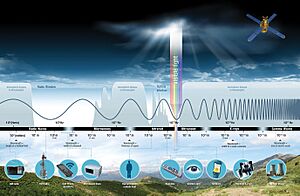

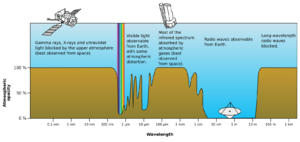

The electromagnetic spectrum is like a giant rainbow of all the different kinds of electromagnetic radiation. These are waves of energy that travel through space. We organize them by their frequency (how many waves pass a point each second) or their wavelength (the distance between two wave peaks).

The spectrum has different sections, each with its own name. From the lowest frequency to the highest, these are: radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays, and gamma rays. Each type of wave has unique features. They are made in different ways and interact with matter differently. They also have many practical uses in our daily lives.

Radio waves are at the low-frequency end. They have the longest wavelengths, sometimes thousands of kilometers long. They carry the least amount of energy. We use antennas to send and receive them. They can travel through the air, plants, and most buildings.

Gamma rays are at the high-frequency end. They have the shortest wavelengths, much smaller than an atomic nucleus. They carry the most energy. Gamma rays, X-rays, and extreme ultraviolet rays are called ionizing radiation. This means their high energy can change atoms, causing chemical reactions. Longer waves, like visible light, are nonionizing. Their energy is not enough to change atoms in this way.

Scientists use a method called spectroscopy to study these waves. It helps them separate waves by frequency. This lets them measure how much radiation there is at different frequencies. Spectroscopy helps us understand how electromagnetic waves interact with everything around us.

Contents

Discovering Electromagnetic Waves

Humans have always known about visible light and radiant heat. But for a long time, people did not know these were connected. They also didn't know these were part of a bigger system. Ancient Greeks studied light, seeing how it traveled in straight lines. They also learned about reflection and refraction.

In the 1600s, people studied light more closely. This led to inventions like the telescope and microscope. Isaac Newton first used the word spectrum. He used it for the colors that white light splits into when it passes through a prism. Newton showed that these colors were part of light itself. He also showed they could be combined back into white light.

In 1800, William Herschel found infrared radiation. He used a thermometer to measure the temperature of different colors of light. He saw the highest temperature was beyond the red light. He called these "calorific rays," a type of light we cannot see. The next year, Johann Ritter found "chemical rays" beyond violet light. These invisible rays caused certain chemical reactions. They were later named ultraviolet radiation.

The study of electromagnetism began in 1820. Hans Christian Ørsted found that electric currents create magnetic fields. In 1845, Michael Faraday linked light to electromagnetism. He saw that light's polarization changed when it passed through a magnetic field.

During the 1860s, James Clerk Maxwell created equations for the electromagnetic field. These equations predicted that waves could exist in this field. He realized these waves would travel at the speed of light. This amazing discovery led Maxwell to believe that light itself is an electromagnetic wave. His equations showed there was an endless range of these waves. This was the first hint of the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

In 1886, Heinrich Hertz built a device to create and detect radio waves. He proved Maxwell's ideas were correct. Hertz showed these new waves traveled at the speed of light. He also showed they could be reflected and refracted, just like light. His work led to inventions like the wireless telegraph and the radio.

In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen discovered x-rays. He found these new rays could pass through parts of the human body. Denser things, like bones, would block them. Soon, X-rays were used for radiography in medicine.

The last part of the spectrum to be found was gamma rays. In 1900, Paul Villard was studying radium. He found a new type of radiation that was very powerful. In 1914, Ernest Rutherford and Edward Andrade measured their wavelengths. They found gamma rays were like X-rays, but with even shorter wavelengths.

Scientists now understand that electromagnetic radiation acts both like a wave and like a particle. This idea is called wave-particle duality.

How EM Waves are Measured

Electromagnetic waves are described by three main features. These are their frequency (f), wavelength (λ), and photon energy (E).

- Wavelength is the distance between two peaks of a wave.

- Frequency is how many waves pass a point in one second.

- Photon energy is the amount of energy each tiny packet of light (a photon) carries.

These three features are connected. When one changes, the others change too.

- Waves with high frequency have short wavelengths and high energy.

- Waves with low frequency have long wavelengths and low energy.

This relationship is shown by these simple rules:

- Frequency is the speed of light divided by wavelength.

- Energy is the Planck constant multiplied by frequency.

- Energy is the Planck constant times the speed of light, divided by wavelength.

The speed of light in a vacuum is a constant, c. The Planck constant (h) is also a constant.

When electromagnetic waves travel through materials, their wavelength can change. However, we usually talk about their wavelength in a vacuum.

Scientists use spectroscopy to study a very wide range of the EM spectrum. This is much wider than just the visible light we can see. These tools help us learn about objects, gases, and even distant stars. For example, hydrogen atoms can send out radio waves with a wavelength of 21.12 centimeters.

Different Types of EM Waves

The electromagnetic spectrum is divided into different types of radiation. These are often called regions, bands, or classes. They are listed here from the shortest wavelength (highest energy) to the longest wavelength (lowest energy):

- Gamma radiation

- X-ray radiation

- Ultraviolet radiation

- Visible light (the light humans can see)

- Infrared radiation

- Microwave radiation

- Radio waves

There are no sharp lines between these bands. They blend into each other, much like the colors in a rainbow. Waves in one region often share some properties with the regions next to them. For example, red light is similar to infrared radiation. It can add energy to some chemical bonds. This is important for things like photosynthesis in plants and how our eyes see.

In physics, the difference between X-rays and gamma rays often depends on where they come from. Gamma rays usually come from changes inside an atomic nucleus. X-rays come from changes involving the electrons around an atom. In space science, X-rays are usually energies below 100 keV, and gamma rays are higher energies.

| Class | Wave- length  |

Freq- uency  |

Energy per photon  |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizing radiation |

γ | Gamma rays | 10 pm | 30 EHz | 124 keV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 pm | 3 EHz | 12.4 keV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HX | Hard X-rays | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SX | Soft X-rays | 10 nm | 30 PHz | 124 eV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EUV | Extreme ultraviolet |

121 nm | 3 PHz | 10.2 eV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NUV | Near ultraviolet |

400 nm | 750 THz | 3.1 eV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Visible spectrum | 700 nm | 480 THz | 1.77 eV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Infrared | NIR | Near infrared | 1 μm | 300 THz | 1.24 eV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 μm | 30 THz | 124 meV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MIR | Mid infrared | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 μm | 3 THz | 12.4 meV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FIR | Far infrared | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 mm | 300 GHz | 1.24 meV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Micro- waves |

EHF | Extremely high frequency |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 cm | 30 GHz | 124 μeV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SHF | Super high frequency |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 dm | 3 GHz | 12.4 μeV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UHF | Ultra high frequency |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 m | 300 MHz | 1.24 μeV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Radio waves |

VHF | Very high frequency |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 m | 30 MHz | 124 neV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HF | High frequency |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 m | 3 MHz | 12.4 neV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MF | Medium frequency |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 km | 300 kHz | 1.24 neV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LF | Low frequency |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 km | 30 kHz | 124 peV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| VLF | Very low frequency |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 km | 3 kHz | 12.4 peV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Band 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 Mm | 300 Hz | 1.24 peV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Band 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 Mm | 30 Hz | 124 feV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | Band 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 Mm | 3 Hz | 12.4 feV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sources Table shows the lower frequency limits (and higher wavelength limits) for the specified class

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How EM Waves Interact with Matter

Electromagnetic radiation interacts with matter in different ways across the spectrum. These interactions are so varied that, historically, different names were given to different parts of the spectrum. This is why the spectrum is still divided, even though it's a continuous range of frequencies and wavelengths.

| Region of the spectrum | Main interactions with matter |

|---|---|

| Radio | Causes charges to move back and forth in materials. For example, electrons moving in an antenna. |

| Microwave through far infrared | Causes charges to move and molecules to spin. |

| Near infrared | Causes molecules to vibrate. Also moves charges in metals. |

| Visible | Excites electrons in molecules (like in our eyes or plant pigments). Also moves charges in metals. |

| Ultraviolet | Excites and can remove electrons from molecules and atoms (photoelectric effect). |

| X-rays | Excites and removes electrons from inner parts of atoms. Can also scatter off electrons (Compton scattering). |

| Gamma rays | Removes electrons from heavy atoms. Scatters off electrons. Can excite or even break apart atomic nuclei. |

| High-energy gamma rays | Can create new particles and antiparticles when interacting with matter. |

Types of Radiation and Their Uses

Radio Waves: Longest Waves

Radio waves are sent and received by antennas. These are often metal rods. To create radio waves, an electronic device called a transmitter makes an electric current. This current flows into an antenna. The moving electrons in the antenna create electric and magnetic fields. These fields then travel away as radio waves.

To receive radio waves, the waves' electric and magnetic fields push electrons in an antenna. This creates currents that a radio receiver can pick up. Earth's atmosphere lets most radio waves pass through. However, layers of charged particles in the ionosphere can reflect some frequencies.

Radio waves are used everywhere to send information over distances. This includes radio broadcasting, television, mobile phones, communication satellites, and wireless networking. In these systems, information is added to the radio wave. The wave then carries this information to a receiver.

Radio waves also help with navigation, like in Global Positioning System (GPS). They are used to find distant objects with radar. Other uses include remote control and heating things in factories. Governments carefully manage how the radio spectrum is used.

Microwaves: Short and Useful

Microwaves are short radio waves. Their wavelengths range from about 10 centimeters to one millimeter. They are used in SHF and EHF bands. Microwaves are made using special tubes or solid-state devices.

Microwaves can be sent and received by small antennas. They are also absorbed by certain molecules, causing them to vibrate and heat up. Unlike visible light, which mostly heats surfaces, microwaves can go inside materials and heat them from within. This is how microwave ovens cook food. They are also used for industrial heating and medical treatments.

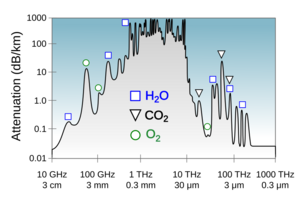

Microwaves are key in radar systems. They are also used for satellite communication and wireless networking like Wi-Fi. Special metal pipes called waveguides carry microwaves. This is because regular copper cables lose too much power at these frequencies. While the lower microwave frequencies pass through the atmosphere easily, higher frequencies are absorbed by atmospheric gases. This limits how far they can travel.

Infrared: Heat and Beyond

The infrared part of the spectrum ranges from about 300 GHz to 400 THz. This is from 1 millimeter to 750 nanometers. It has three main parts:

- Far-infrared: From 1 mm to 10 μm. This radiation is absorbed by molecules spinning and vibrating. Water in Earth's atmosphere strongly absorbs these waves, making the atmosphere mostly opaque. However, some "windows" allow partial transmission for astronomy.

- Mid-infrared: From 10–2.5 μm. Hot objects, like our bodies, radiate strongly in this range. This radiation is absorbed by molecules vibrating. Each compound has a unique mid-infrared absorption pattern, like a "fingerprint."

- Near-infrared: From 2,500–750 nm. These waves behave similarly to visible light. Some cameras and photographic films can detect them for infrared photography.

Visible Light: What We See

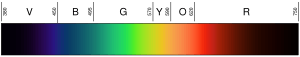

| Colour | Wavelength (nm) |

Frequency (THz) |

Photon energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| violet | 380–450 | 670–790 | 2.75–3.26 |

| blue | 450–485 | 620–670 | 2.56–2.75 |

| cyan | 485–500 | 600–620 | 2.48–2.56 |

| green | 500–565 | 530–600 | 2.19–2.48 |

| yellow | 565–590 | 510–530 | 2.10–2.19 |

| orange | 590–625 | 480–510 | 1.98–2.10 |

| red | 625–750 | 400–480 | 1.65–1.98 |

Above infrared in frequency is visible light. The Sun gives off most of its power in this region. Visible light is the part of the EM spectrum that the human eye can see. It is absorbed and emitted by electrons moving between energy levels in atoms and molecules. This process is vital for human vision and plant photosynthesis.

The light that our eyes can detect is a very small part of the electromagnetic spectrum. A rainbow shows the visible part of the spectrum. Infrared would be just beyond the red, and ultraviolet just beyond the violet.

Light with a wavelength between 380 nm and 760 nm is seen by human eyes. We perceive this as visible light. White light is a mix of all these colors. Passing white light through a prism splits it into its different colors.

When visible light reflects off an object, like a bowl of fruit, and enters our eyes, we see the object. Our brain processes the different reflected frequencies into colors and shades. This allows us to see the world around us.

Most information carried by electromagnetic radiation is not directly detected by our senses. But technology uses a wide range of wavelengths. Optical fibers, for example, transmit light (often infrared) to carry information.

Ultraviolet: Invisible Sun Rays

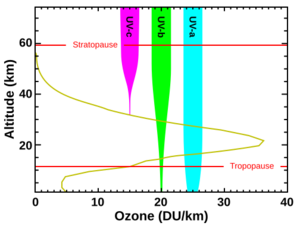

Next in frequency comes ultraviolet (UV) light. UV rays are between the violet end of the visible spectrum and the X-ray range. The UV spectrum goes from 399 nm to 10 nm. It is divided into three sections: UVA, UVB, and UVC.

UV is the lowest energy range that can ionize atoms. This means it can remove electrons from them, causing chemical reactions. UV, X-rays, and gamma rays are called ionizing radiation. Exposure to them can harm living tissue. UV can also make some substances glow with visible light, a process called fluorescence. UV fluorescence is used in forensics to find evidence and to check for fake money or IDs.

Mid-range UV rays (UVB) cannot ionize atoms but can break chemical bonds. This makes molecules very reactive. Sunburn is caused by UVB radiation damaging skin cells. This is a main cause of skin cancer. UVB rays can also damage DNA molecules in cells. Sunscreen helps protect against UV damage. UVB lights, like germicidal lamps, are used to kill germs and sterilize water.

The Sun emits UV radiation, about 10% of its total power. Some of this UV is very short wavelength and could harm life on Earth. However, most of the Sun's harmful UV is absorbed by our atmosphere. Higher energy UV (called "vacuum UV") is absorbed by nitrogen and oxygen in the air. Most mid-range UV is blocked by the ozone layer. This leaves less than 3% of sunlight at sea level as UV, mostly lower-energy UV-A. UV-A is not blocked well by the atmosphere and can still cause skin damage and mutations, though it doesn't cause sunburn.

X-rays: Seeing Inside Things

After UV come X-rays. Like high-energy UV, X-rays are also ionizing. But because they have higher energies, X-rays can also interact with matter through the Compton effect. Hard X-rays have shorter wavelengths than soft X-rays. They can pass through many substances with little absorption. This allows them to "see through" objects.

A common use is in medicine for diagnostic X-ray imaging, known as radiography. X-rays are also useful for studying high-energy physics. In astronomy, hot gas around neutron stars and black holes emits X-rays. This helps scientists study these objects. X-ray telescopes must be placed outside Earth's atmosphere. This is because our atmosphere is very thick and blocks almost all astronomical X-rays.

Gamma Rays: Most Powerful Waves

After hard X-rays come gamma rays. These were discovered by Paul Ulrich Villard in 1900. They are the most energetic photons and have no defined lower limit to their wavelength. In astronomy, gamma rays are valuable for studying very high-energy objects or regions. Like X-rays, these studies require telescopes outside Earth's atmosphere.

Physicists use gamma rays in experiments because of their strong penetrating ability. They are produced by certain radioisotopes. Gamma rays are used to sterilize foods and seeds. In medicine, they are sometimes used in radiation cancer therapy. More commonly, gamma rays are used for diagnostic imaging in nuclear medicine, such as in PET scans. The wavelength of gamma rays can be measured very accurately using the effects of Compton scattering.

See also

In Spanish: Espectro electromagnético para niños

In Spanish: Espectro electromagnético para niños

- Bandplan

- Cosmic ray

- Electroencephalography

- Infrared window

- Ionizing radiation

- Optical window

- Ozone layer

- Radiant energy

- Radiation

- Radio window

- Spectral imaging

- Spectroscopy

- V band

- W band