Flint-Goodridge Hospital facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Flint-Goodridge Hospital |

|

|---|---|

Flint-Goodridge Hospital of Dillard University

|

|

| Geography | |

| Location | uptown New Orleans, Louisiana, United States |

| Coordinates | 29°56′12″N 90°05′40″W / 29.936602°N 90.094437°W |

| History | |

| Closed | 1983 |

Flint-Goodridge Hospital was an important hospital in uptown New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. It was located at 2425 Louisiana Avenue. For nearly 100 years, from 1896 to 1983, it mainly served African-American patients. For most of this time, Dillard University, a university created for African-American students, owned and ran the hospital.

Contents

A Hospital's Journey: History of Flint-Goodridge

Starting Small: Early Years (1896–1928)

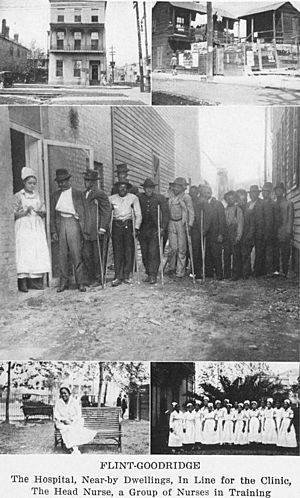

The hospital's story began in 1896. It started as the Phyllis Wheatley Sanitarium and Training School for Negro Nurses. A "sanitarium" was a place for medical care. The Phillis Wheatley Club ran this school and hospital. It was part of New Orleans University, which was supported by the Methodist Episcopal Church.

The school needed more money to keep the hospital going. So, New Orleans University took it over. A bishop named Willard Francis Mallalieu helped get financial aid. John Flint from Massachusetts donated $25,000 to the hospital. In 1901, the hospital was renamed Sarah Goodridge Hospital and Nurse Training School. The medical college became Flint Medical College, honoring John Flint. He later gave another $10,000 to buy a new building.

In 1911, the Flint Medical College closed. Its facilities were not good enough by new medical standards. In 1915, the School of Pharmacy also closed. All the buildings were then used by the Sarah Goodridge Hospital. The hospital was renovated in 1916. It became a 50-bed hospital with a nurse's residence. The hospital was then renamed Flint-Goodridge Hospital. Its Nurse Training Department continued under New Orleans University.

Under Dillard University (1929–1983)

In 1930, New Orleans University and Straight College joined together. They formed Dillard University, a university for African-American students. Dillard University then became the owner and operator of the hospital. A big fundraising effort began to build a brand new hospital. The new building was put up in Uptown New Orleans. It opened on February 1, 1932, at 2425 Louisiana Avenue.

Leading the Way: Albert Walter Dent's Time

In 1929, Dillard's leaders chose 27-year-old Albert Walter Dent to be the hospital's superintendent. He was a dynamic and capable leader. Dent faced a challenge: finding ways for his African-American doctors to complete their training. During segregation, there were few opportunities for them.

Dent found a solution. He asked white doctors from Tulane and Louisiana State University to help. These doctors became consultants for the hospital's departments. They held regular training sessions for the doctors. This cooperation between Black and white doctors was seen as a great example. The new hospital building, designed by Moise Goldsteinat, cost about half a million dollars. It opened in 1932.

During Dent's time, the hospital started special courses for doctors in the South. Dent also increased the number of free hospital beds from 20% to 50%. He lowered costs and used programs from the New Deal (government programs to help during the Great Depression). These programs, like the National Youth Administration, helped train nurses and orderlies. This meant the hospital could use its own money for patient care. For example, they offered maternity care for a flat rate of ten dollars. Dent also tried to get more paying patients. He offered a "one cent pay-a-day" plan, with help from a donation.

In 1941, Dent left the hospital to become Dillard University's third president. He served for 28 years. His next two successors at the hospital had short and difficult times, especially during World War II. The hospital began to struggle with debt.

Growth and Change: Clifton Caldwell Weill's Leadership

In 1949, Clifton Caldwell Weill, who had learned from Dent, became the superintendent. He led the hospital until 1970. In 1953, a separate board was created just for the hospital. Mrs. Albert Walker Dent, the previous superintendent's wife, came up with an idea to raise money. She planned fashion shows and got help from John H. Johnson, who published Jet and Ebony magazines. The first Ebony fashion fair for the hospital happened in 1958. Over the years, this fair became a traveling event that raised money for many causes, including Flint-Goodridge Hospital.

In 1958, Weill started a campaign to build a new part of the hospital. They raised over $1.3 million. A new four-story wing with 96 beds was finished in 1960. This allowed the Physical Therapy Department to grow. The hospital also got new features like piped air, room telephones, and an intercom system for nurses and patients. An intensive care unit was built in 1963. A coronary unit, with the latest heart monitors and devices, was added in 1968. Also in 1968, a new residence for nurses was built nearby. Weill completed his 21st and final year as superintendent in 1970.

The Hospital's Closing Years

After the 1960s, new laws ended segregation. This meant African-American patients could go to any hospital. As a result, Flint-Goodridge Hospital saw fewer patients. This led to its eventual closure. An effort was made to sell the hospital to a group of African-American doctors, but it didn't work out.

In 1983, the hospital was sold to a company called National Medical Enterprises. However, they decided not to use the building as a hospital. So, Flint-Goodridge Hospital closed its doors. The building still stands today at 2425 Louisiana Avenue. It is now called the Flint-Goodridge Apartments.

A Lasting Impact: Legacy of Flint-Goodridge

For much of the 1900s, Flint-Goodridge Hospital was a very important place. It was owned by African Americans and served the needs of the Black community in New Orleans. Many well-known Black doctors worked at Flint-Goodridge during their careers. The hospital played a key role in providing healthcare and training for African Americans during a time of segregation.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |