Freda DeKnight facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Freda DeKnight

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Freda Alexander

December 20, 1909 near Topeka, Kansas, United States

|

| Died | January 30, 1963 New York City, United States

|

| Occupation | Editor, author |

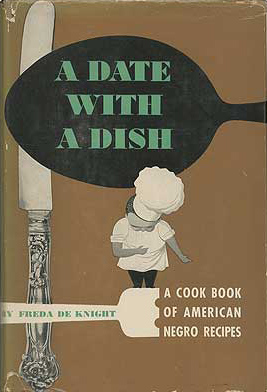

Freda DeKnight (1909–1963) was a very important person in the world of food and magazines. She was the first food editor for Ebony magazine. She also wrote a famous cookbook called A Date With A Dish: A Cookbook of American Negro Recipes. This book is known as the first major cookbook written by an African-American author for an African-American audience. Freda DeKnight was a pioneer who showed a great love for food. Her cookbook is still used today, keeping her legacy alive.

Contents

Early Life and Cooking Passion

Freda Alexander was born in December 1909. Her mother, Elenore Alexander, was a nurse from Boston. Freda was born while her mother was traveling near Topeka, Kansas. When Freda was two, her father passed away. He worked on the Santa Fe Railroad.

Freda's mother, a traveling nurse, sent Freda and her sister to live with a farming family in South Dakota. This family, the Scotts, raised animals and grew crops. They also ran a very successful catering business. Freda quickly became very interested in cooking. Her adoptive family helped her learn and grow this passion.

DeKnight later remembered the Scotts as her inspiration. She said they gave her every chance to learn their recipes. She learned how to cook, prepare food, and cater. Even though "Mama Scott" didn't have much schooling, she could measure and estimate perfectly. Freda later turned this love for cooking into her career. She studied home economics at Dakota Wesleyan University. After that, she moved to New York and started working at Ebony in 1944.

A Career in Food and Fashion

After college, Freda DeKnight moved to New York. She took classes at Columbia University and New York University. She also taught sewing and worked as a guidance counselor. She helped students at vocational training schools in Manhattan. At Yorkville High School, she met René DeKnight. He was a pianist for The Delta Rhythm Boys. They got married in 1940.

In 1946, DeKnight became the food editor for Ebony magazine. This made her the first African-American food editor in the United States. The story goes that she cooked a meal for John H. Johnson, the publisher of Ebony. He loved the meal and asked for the menu. DeKnight sent it to him in a fun, story-like way. This made cooking seem exciting. She used this creative style in her magazine column. For example, cooking steps would appear as photo captions.

DeKnight wrote a regular column in Ebony called “A Date with a Dish.” Her husband, Rene DeKnight, came up with the name. As the first food editor, she wrote a monthly column with many photos. She shared tips from her home economics knowledge. She also shared recipes from the "Negro community." These recipes came from home cooks, chefs, caterers, restaurants, and even celebrities.

The Famous Cookbook

In 1948, DeKnight published her only cookbook. It was called A Date with A Dish: A Cookbook of American Negro Recipes. This book is seen as the first major cookbook written by an African-American for an African-American audience. Through Ebony, DeKnight showed readers how Southern cooking had roots from many different cultures. She also highlighted the clever ways people created dishes. This cleverness helped cooking rise above the poverty from which traditional Southern cooking often came.

Charlotte Lyons, another Ebony food editor, said that Freda DeKnight was a pioneer. She helped translate Ebony's message of education and dignity into the recipes she shared.

Beyond the Kitchen

DeKnight did more than just celebrate African-American culture through food. She became the home service director at Johnson Publishing, which owned Ebony. In 1957, she started the first Ebony Fashion Fair. This event mixed "Negro culture" with international haute couture (high fashion). She often appeared on television, showing how to make recipes like violet-petal cake. She also traveled the country to find models for Ebony magazine.

In 1962, DeKnight's husband took her on a trip to Hawaii and Japan. While there, she chose fashions for the 1962 Ebony Fashion Fair. It was called "The Fashion Fair With An Oriental Flair."

A Date with a Dish Cookbook

In 1948, Freda DeKnight released her only cookbook, A Date with a Dish. Later versions of the book were called The Ebony Cookbook. However, in 2014, the book was re-released with its original title.

This cookbook was much more than just a collection of her magazine columns and recipes. DeKnight traveled all over the country to interview people and gather recipes. She spoke with famous people like Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. She also talked to respected African-American chefs and home cooks. The result was a 400-page cookbook. It included recipes, menus, and cooking tips from African-Americans across America.

DeKnight used a popular style for home cooks. She offered clear, organized recipes and many household tips. She suggested colorful vegetable platters for spring and holiday meals. She gave simple, clear instructions for preparing lobster. She also added fun stories into her cooking directions. DeKnight shared touching and funny moments from her interviews with celebrities. She also included their favorite recipes. For example, Louis Armstrong's beloved ham hocks and red beans.

Louis Armstrong was quoted in her book saying: “No need to make folks think I like fancy foods like quail on toast, chicken and hot biscuits, or steak smothered in mushrooms. Of course they taste good and I can eat them, but have you ever tried ham hocks and red beans?”

DeKnight wanted to do more than just write a great cookbook, even though it became a bestseller. She aimed to change wrong ideas about African-American cooks and Southern cooking. In her book's introduction, she wrote that it's a mistake to think African-American cooks can only make Southern dishes. She said that like other Americans, they want to be good at making all kinds of food.

Freda DeKnight's Legacy

The Paris Review said that DeKnight showed a more detailed and often glamorous picture of African-American cooking and culture. She shared this not just with African-American readers, but with the whole world. DeKnight's work helped people understand Southern cooking as a mix of cultures. It also showed how food could be a way to improve one's life.

One food editor said that DeKnight gave people "permission to celebrate the wide diversity of what African Americans cooked and ate." Before her work, some people didn't believe that African-Americans enjoyed making Chinese, French, Italian, and other ethnic dishes. They thought, "You don't really own that because that's white food."

Without DeKnight's work, people might still think African-American food is only a small range of dishes. She showed that African-Americans have been cooking all kinds of food from the very beginning.

Later Life and Death

In 1960, Freda DeKnight had surgery for cancer. Even so, she kept traveling with the fashion fair until 1962. Her illness became worse, and she grew weaker. She passed away in 1963 at the age of 53.

DeKnight's obituary was in the August 1963 issue of Negro Digest. It was titled "Tribute To A Lady Titan." The writer noted her role in changing how African-Americans were seen in public. They called DeKnight "a familiar figure at professional food and fashion gatherings where Negroes had been seen before only as servants." She opened doors for future generations to choose many different careers.