Great Council of Venice facts for kids

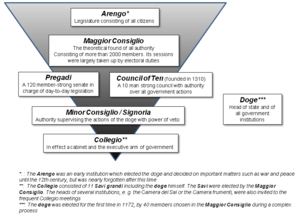

The Great Council or Major Council (in Italian, Maggior Consiglio) was a very important government group in the Republic of Venice. It existed for a long time, from 1172 until 1797. This council was the main meeting place for politics in Venice. It was in charge of choosing many other government officials and senior councils. It also made laws and watched over the justice system.

After an event called the Serrata (which means "lock-out") in 1297, only certain noble families could be members. These families were listed in a special book called the Golden Book of the Venetian nobility. The Great Council was special because it used a lottery system to pick people who would suggest new members. These suggested members were then voted on.

Contents

History of the Great Council

It's not totally clear how the Great Council first started. Many believe it began in 1172. But it might have grown from an older group called the 'Council of Wise Men,' which existed in 1141. This older council was created to limit the power of the Doge of Venice, who was Venice's leader. Noble families mostly controlled this early council.

Early Days of the Council

The Great Council took over from an older public meeting called the Concio. The Concio only met to agree on laws and choose a new Doge. The Great Council's job was to elect all government officials and approve laws. It also handled some court cases, like granting pardons.

However, the Great Council was very large, with 300 to 400 members by the 1200s. Because it was so big, smaller councils did most of the real talking and decision-making. In the 13th century, the most important of these was the Council of Forty. This council was the highest court and also helped prepare laws for the Great Council to vote on. The Doge, six special advisors (called ducal councillors), and the three leaders of the Council of Forty formed the Signoria of Venice. This group was the true government of Venice.

In its early years, the Great Council was quite open. Anyone who was a free citizen could, in theory, become a member. Three electors chose the members. It's not fully known how these electors were picked, but it involved some luck (lottery) and taking turns. In 1230, the way electors were chosen changed. Seven electors served for part of the year, and three for the rest. But the number of electors often changed.

These electors chose 100 people to be members for the next year. Since there weren't other choices, the people they picked were always elected. This system gave a lot of power to a few electors. Also, some officials, like the ducal councillors, were automatically members. They often outnumbered the elected members. A historian named Frederic C. Lane said that the Great Council included "all the most important people who were available in Venice."

The Serrata (Lock-out) of the Great Council

The Great Council was very important because it chose who got government jobs. This made it "the gatekeeper for power and prestige in Venice." During the 1200s, there was a struggle. Some people wanted to let more new people join the Council and the political elite. Others wanted to keep power with the old noble families.

Even though noble families were common, ordinary citizens were still sometimes members. But even among the nobles, there were disagreements. Venice's population and wealth grew, so more citizens wanted to join the Great Council. But the old noble families didn't want these "new rich" people to join. There was also the issue of foreigners. These were nobles from Venice's growing empire or from other places. They were counted as Venetian citizens but were culturally different.

There were ideas for changes. In 1286, leaders of the Council of Forty suggested that only those whose ancestors had been members would automatically be considered. Others would need approval from the Doge and other councils. This idea didn't pass. Another idea, to have new members approved by a majority of the current Council, also failed.

Things became tense in 1289 when Doge Giovanni Dandolo died. A crowd gathered and demanded that Admiral Giacomo Tiepolo, whose father and grandfather had been Doges, be the new Doge. The Great Council hesitated, but Tiepolo refused. So, the Council elected Pietro Gradenigo instead.

This was a key moment. If the crowd had won, Venice might have ended up like other Italian cities, with rulers chosen by family or by angry mobs. After he was elected, Doge Gradenigo worked hard to pass a reform that everyone could agree on. This happened on February 28, 1297, and is known as the Serrata or "lock-out."

The Serrata made sure that current members, or those who had been members in the past four years, would stay members if they got at least 12 votes in the Council of Forty. This basically guaranteed their spots. Also, the limit on the size of the Great Council was removed. A new law allowed three current members to suggest new candidates. These candidates had to be approved by the Doge, the Minor Council, and the Council of Forty.

Because of this, several old commoner families became permanent members. About a dozen families who fled after the fall of Acre in 1291 also joined. The Great Council more than doubled in size to over 1,100 members by 1300. This was about 1% of Venice's total population at the time.

This opening up of the ruling class seemed to satisfy ambitious people and calm things down. Although, one commoner, Marin Bocconio, who felt he should have been admitted, was executed in 1300 for planning to kill Gradenigo. It's interesting that this reform happened during a difficult war with Venice's rival, the Republic of Genoa. The common people did not seriously oppose it.

Over the next few years, it became harder for new members to join. The number of votes needed in the Forty increased. By 1319, membership became automatic for men at age 25, except for 30 men chosen by lottery who could join at 20. In 1323, membership was only for men whose ancestors had held high office. This made membership basically hereditary.

From then on, the permanent members of the Great Council became the nobility of Venice. This new ruling class had almost 200 families. They controlled the highest levels of power in the Republic. Very rarely, deserving men who did great things were still allowed to join later. To help wealthy and important families who weren't nobles, a new group called 'citizens' (cittadini) was created. This was a middle class between the closed nobility and the common people.

Some historians have called the Serrata "the death of the Venetian republican system." But actually, these changes were mostly good. They saved Venice from the bitter fights between groups that happened in other Italian cities. Unlike the unpredictable public assembly, members of the Great Council were guaranteed a share in power. This made them harder to control. The large number of families in this ruling group was also special for Venice. It made the government more representative and helped keep rivalries between families in check.

From the 14th Century to the End

For the rest of Venice's history, the Great Council was the most powerful part of the government. It replaced the old Concio, which was officially ended in 1423. The Great Council kept its power to make laws. But many of its duties were given to other, smaller groups that could act faster.

Soon, the Venetian Senate took over most of the main government jobs, like choosing military leaders or meeting with ambassadors. Over the 1400s and 1500s, the Senate also became the main group for making laws. The Great Council mostly discussed or approved things already decided by the Senate. But it kept its power over justice and its right to elect officials.

The rules for joining the Great Council became stricter over time. Men born to women of lower social status were not allowed. After 1498, nobles who became priests were also banned. These rules led to the creation of special records of births and marriages for noble families in 1506 and 1526. These records were kept by the Avogadori de Comùn and became the famous 'Golden Book' (Libro d'Oro) of the Venetian nobility. At this point, the council reached its largest size, with 2,746 members.

The Serrata had greatly increased the number of members. In the 1500s, it was common for up to 2,095 nobles to have the right to sit in the Doge's Palace. It was clearly difficult to manage such a large group.

Because the group grew so much, a larger meeting space was needed. This need was noticed early on, and a hall was made bigger in the buildings along the Molo, which is the waterfront next to the Doge's Palace. As the Council kept growing in the early 1300s, it was decided that a new part of the Doge's Palace should be built to hold them.

The new hall for the Great Council started being used around 1420. This hall was destroyed in a fire on December 20, 1577. The Doge's Palace was so badly damaged that people thought about tearing it down and rebuilding it. But they decided to restore it instead. During this time, the Great Council met in a storage building at the Arsenal of Venice.

In a few rare cases, when Venice faced serious money problems or dangers, new families were allowed to join the Great Council. This happened during the War of Chioggia and the War of Candia. Wealthy new families were admitted by giving large gifts to the state to help pay for the huge costs of these wars.

Another interesting thing was that the nobility itself became divided. Some families managed to keep or increase their wealth. Others became poor, known as the Barnabites. These poor nobles still had the right to be in the Great Council. This often led to clashes between the rich and poor nobles in the council. It also opened the door for people to buy votes.

It was the Great Council, on May 12, 1797, that declared the end of the Republic of Venice. Because of the Napoleonic invasion, the Council voted to accept the last Doge Ludovico Manin stepping down. They also decided to end the aristocratic assembly. Even though not enough members were present (they needed 600), the vote was strongly in favor (512 for, 30 against, 5 not voting) of ending the Venetian Republic and giving power to a temporary government.

Images for kids

See also

- Minor Council

- Council of Forty

- Signoria of Venice

- Concio (Venice)

- Serrata del Maggior Consiglio

- Venetian nobility

- Seven Noble Houses of Brussels