Hōnen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hōnen (法然) |

|

|---|---|

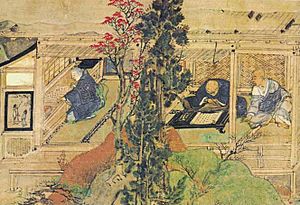

Portrait of Honen by Fujiwara Takanobu, 12th Century

|

|

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Jōdo-shū school of Pure Land Buddhism |

| Lineage | Tendai, Sammon lineage |

| Other names | Genkū (源空) |

| Personal | |

| Born | Seishimaru May 13 (April 7), 1133 Kume, Okayama Prefecture, Japan |

| Died | February 29, 1212 (aged 78) Kyoto, Japan |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | Founder of Jōdo-shū |

Hōnen (法然, May 13 (April 7), 1133 – February 29, 1212) was an important religious leader in Japan. He started the first independent branch of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism, which is called Jōdo-shū (浄土宗, "The Pure Land School").

Hōnen became a Buddhist monk at a young age. He was part of the Tendai school of Buddhism. However, he felt that its teachings were too difficult for most people to follow. He wanted to find a simpler way for everyone to reach enlightenment.

He found the writings of a Chinese Buddhist teacher named Shandao. These writings taught that people could be reborn in the pure land of Amitābha Buddha. This could happen just by saying the Buddha's name, a practice called nianfo (or nembutsu in Japanese).

Hōnen's teachings became very popular, and he gained many followers. But he also faced criticism from other Buddhist groups. In 1207, the Emperor sent Hōnen and some of his followers away from the capital city. Hōnen was later allowed to return to Kyoto, where he passed away shortly after.

Contents

Hōnen's Life Story

Early Years

Hōnen was born in 1133 in a place called Kume, in what is now Okayama Prefecture. His birth name was Seishimaru. His father was an important local official.

When Hōnen was just eight years old, his father was sadly killed. It is said that his father's last wish was for Hōnen to become a monk and pray for him.

To fulfill his father's wish, Hōnen joined a monastery when he was nine. He spent his life as a monk and later studied at Mount Hiei. This was the main temple of the Tendai Buddhist school near Kyoto. Monks at Mount Hiei took special vows and trained for 12 years.

While at Mount Hiei, Hōnen studied with several teachers. He was officially ordained as a Tendai priest. He was given the name Hōnen-bō Genkū. His close students often called him Genkū.

Leaving Mount Hiei

Hōnen spent a lot of time at Mount Hiei trying to find a way for everyone to find peace and happiness through Buddhism. But he wasn't satisfied with what he learned there. When he was 24, he traveled to other temples in cities like Saga and Nara, including Kōfuku-ji and Tōdai-ji.

Still searching, he returned to Mount Hiei's libraries. There, he read a special Pure Land Buddhist text. It was called the Commentaries on the Amitayurdhyana Sutra. This book was written by a Chinese master named Shandao.

Hōnen was especially moved by a part that said: "Only repeat the name of Amitabha with all your heart. Whether walking or standing, sitting or lying, never cease the practice of it even for a moment. This is the very work which unfailingly issues in salvation..."

This idea convinced Hōnen that simply saying the nembutsu (Amitābha's name) was enough to reach Amitābha's pure land. Before this, people usually said the nembutsu along with many other practices. But Shandao was the first to say that only the nembutsu was needed. This new understanding led Hōnen to leave Mount Hiei and the Tendai tradition in 1175.

Starting a New Buddhist School

Hōnen moved to a part of Kyoto called Ōtani. There, he began teaching large groups of people. He quickly gained many followers. His teachings attracted all kinds of people, including fortune-tellers, former robbers, and samurai. These were people who were often not included in traditional Buddhist practices.

Hōnen became well-known in Kyoto. Many priests and noblemen visited him for spiritual advice. One important person who supported him was an imperial regent named Kujō Kanezane.

However, the growing popularity of Hōnen's teachings also led to criticism. Other Buddhist leaders, like Myōe and Jōkei, disagreed with Hōnen's idea that only nembutsu was needed. Some of Hōnen's students also caused problems by acting disrespectfully or criticizing other Buddhist groups.

In 1204, monks at Mount Hiei asked their leader to ban Hōnen's teachings. In 1205, the temple of Kōfuku-ji in Nara asked the Emperor to punish Hōnen and his followers. They made several accusations. They said Hōnen's focus on only nembutsu meant that other Buddhist practices were seen as useless. They also claimed that Hōnen's teachings made ordinary people equal to wise monks, which they felt made the traditional monastic system seem unimportant.

In response, Hōnen told his followers to behave better. They signed a document called the Shichikajō-kishōmon (七箇条起請文, "Seven Article Pledge"). This pledge asked them to act with good morals and to be respectful toward other Buddhist groups.

The arguments about Hōnen's teachings calmed down for a while. But in 1207, the Emperor banned the practice of exclusive nembutsu. Hōnen and some of his students, including Shinran, were sent away from Kyoto. Two of his students were even executed.

Hōnen is said to have accepted his exile calmly. He saw it as a chance to teach people in the countryside who had not heard his message before.

Exile and Final Years

Hōnen was sent to a place called Tosa. Even though he was exiled, his movement in Kyoto continued. While in exile, Hōnen shared his teachings with the local people, including fishermen and farmers.

In 1211, the ban on nembutsu was lifted, and Hōnen was allowed to return to Kyoto. He passed away in Kyoto in 1212. A few days before his death, he wrote his final important message, called the One-Sheet Document (一枚起請文, Ichimai-kishōmon).

Hōnen's Character

Historians have studied many old documents to understand Hōnen's personality. They describe him as:

- A strict teacher.

- Someone who thought deeply about himself and was willing to admit his own mistakes.

- A brave innovator who brought new ideas.

- Someone who cared more about solving everyday problems than about complex religious theories.

Hōnen was especially concerned about the spiritual well-being of women. He taught them regardless of their social status. He did not believe that menstruation made women spiritually impure, which was a common belief in Japanese religious culture at the time. Because of his views, women often played a more important role in the Jōdo-shū schools than in some other Japanese Buddhist traditions.

Hōnen once said about himself:

I don't have the wisdom to teach others. But Ku Amida Butsu of Hosshō-ji, even though he's not as smart, helps people reach the Pure Land by promoting the nembutsu. After I die, if I could be born again as a human, I would want to be a very simple person and just practice the nembutsu diligently.

Hōnen's Teachings

Important Writings

Hōnen's main book explaining his Pure Land teachings is the Senchaku Hongan Nenbutsushū. He wrote it in 1198 for his supporter, Lord Kujō Kanezane. Hōnen asked that this book not be widely shared until after his death.

His only other written work is his final message, the Ichimai-kishōmon (一枚起請文) or "One-Sheet Document". Most of Hōnen's other teachings were written down by his students or by later Buddhist historians.

Key Ideas

Hōnen's teachings are best summarized in his final work, the One-Sheet Document:

In China and Japan, many Buddhist teachers believe that nembutsu means to meditate deeply on Amida Buddha and the Pure Land. However, I do not understand nembutsu in this way. Saying the nembutsu does not come from studying or understanding its meaning. There is no other reason or way to truly believe in being born in the Pure Land than the nembutsu itself. Saying the nembutsu and believing in birth in the Pure Land naturally brings about true faith and practice. If I am hiding any deeper knowledge beyond simply saying the nembutsu, then may I lose the compassion of Shakyamuni and Amida Buddha and fall out of Amida's loving embrace. Even if those who believe in the nembutsu study all the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha, they should not act proud. They should practice the nembutsu with the honesty of simple followers who don't know much about Buddhist teachings.

I sign this document with my handprint. The Jōdo Shū way of settled faith is fully explained here. I, Genkū, have no other teaching than this. To prevent misunderstandings after I pass away, I make this final statement.

Hōnen's practical advice on practicing the nembutsu can be understood with these two ideas:

If you say the Nembutsu carelessly because you think that just one or ten times is enough to be reborn, then your faith is getting in the way of your practice. If you believe that one or ten times is not enough, because it is taught that you should say the Name constantly, then your practice is getting in the way of your faith. For your faith, accept that rebirth is achieved with a single utterance; for your practice, try to say the Nembutsu throughout your life.

Only repeat the name of Amida with all your heart. Whether walking or standing, sitting or lying, never stop practicing it, not even for a moment. This is the very act that will always lead to salvation... (Hōnen quoting Shan-tao)

Hōnen's Students

By 1204, Hōnen had about 190 students. This number comes from the signatures on the Shichikajō-kishōmon (七箇条起請文, Seven Article Pledge). This pledge was a set of rules for how the Jōdo Shū community should behave.

Some of his most important students who signed the pledge include:

- Benchō (1162–1238), who started the main Chinzei branch of Jōdo-shū. He was sent away in 1207.

- Genchi (1183–1238), Hōnen's personal helper and a good friend of Benchō.

- Shōkū (1147–1247), who started the Seizan branch of Jōdo-shū. He was not exiled.

- Shinran (1173–1263), who started the Jōdo Shinshū branch of Pure Land Buddhism. He was exiled in 1207.

- Ryūkan (1148–1227), who started a branch that focused on saying the nembutsu many times.

- Chōsai (1184–1266), who believed that all Buddhist practices could lead to rebirth in the Pure Land.

- Kōsai (1163–1247), who taught a controversial idea that only one recitation of nembutsu was needed. He was removed from Hōnen's community before the exile.

- Rensei (1141–1208), who used to be a famous samurai named Kumagai no Jirō Naozane.

- Anrakubō (? -1207), who was executed in 1207.

- Jūren (?), who was also executed in 1207.

Many of Hōnen's students went on to create their own branches of Pure Land Buddhism. These branches were based on how they understood Hōnen's teachings.

See also

In Spanish: Hōnen para niños

In Spanish: Hōnen para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |