Habitant token facts for kids

The Habitant token was a special type of coin made in 1837 for use mainly in Lower Canada. These tokens were like a follow-up to other popular coins called "bouquet sous". They showed a Habitant on one side. A Habitant was a traditional French-Canadian farmer, often seen in winter clothes. The other side featured the coat of arms for the City of Montreal.

Big banks in Montreal made these tokens. They came in two values: one penny (also called "deux sous") and half penny (or "un sou"). Lots of these tokens were made. Today, it's quite easy for coin collectors to find them. However, some special kinds are rare and worth more money.

These tokens took the place of the "bouquet sous" that banks in Lower Canada used before. Habitant tokens were used for over 60 years! We even know from old digging sites that they were used in Upper Canada too. Experts call these tokens "semi-regal" because the government allowed them to be made.

Contents

History of the Habitant Token

In 1837, the Bank of Montreal asked Britain for permission to bring in copper tokens. They wanted to bring in tokens worth £5,000. Britain said yes, but only if other big banks in Montreal also helped. The other banks agreed.

They ordered the tokens from a company called Boulton and Watt in Birmingham, England. Each token had the name of the bank that made it. The Bank of Montreal paid £2,000 for its tokens. The other three Montreal banks—City Bank of Montreal, The Quebec Bank, and La Banque du Peuple—each paid £1,000.

This money covered the cost of making the tokens. About 1.8 million half pennies and over 900,000 pennies were made. The tokens arrived in Lower Canada in four groups, starting in May 1838 and ending in late 1839. These new tokens were heavier than the old "bouquet sous". This made them closer to their actual value in copper.

Why They Were Called "Papineau" Tokens

These tokens were also often called "Papineau" tokens. This name came from Louis-Joseph Papineau. He was a leader of the Patriote movement before the Lower Canada Rebellion in 1837–1838. Papineau was famous for wearing habitant clothing almost all the time.

Even though the tokens showed a habitant as a symbol of Lower Canada, the banks probably didn't want them linked to Papineau. The banks, especially the Bank of Montreal, were quite traditional. One coin expert said that any link between the tokens and Papineau was "purely sentimental."

Tokens in Later Years

These tokens were used for a long time after they were first made. In August 1870, the Minister of Finance mentioned them. He said that while new bronze coins were legal, the main copper coins were still these bank tokens. He noted they were "of good quality, and all authorized by law."

He also pointed out a problem: these tokens were worth half a penny or a penny in the old money system. But new things like postage stamps were priced in "cents." He thought it was important to have a single, clear money system. He suggested that if the government accepted the tokens as one and two cents, the public would too. This would help solve the problem.

The next year, in 1871, a law called the Uniform Currency Act was passed. This law officially set the values for Canadian money using a decimal system, based on the dollar.

Design of the Habitant Token

The picture of the Habitant on the front of the coin was designed by James Duncan. This design was first used on the back of a Banque Canadienne one dollar bill. The image shows the Habitant wearing traditional winter clothes. These include a touque (a warm hat), a hooded coat, moccasins, and a "ceinture flechee" (a colorful sash). He also holds a whip in his right hand. Above him, it says "PROVINCE DU BAS CANADA." Below him, it shows the value: "UN SOU" (one sou) or "DEUX SOUS" (two sous).

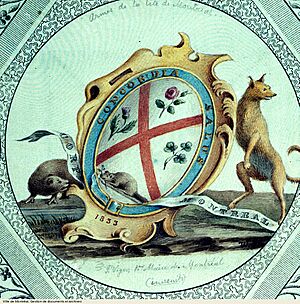

The back of the token shows the first coat of arms for the City of Montreal. This design was created by Mayor Jacques Viger and the city council in 1833. A large "Saint Andrew's Cross" divides the shield into four parts. In each part, there is a symbol for different groups of settlers:

- At the top, a rose for the English heritage.

- A thistle for the Scottish people.

- A sprig of clover for the Irish.

- At the bottom, a beaver for the French settlers who first lived there and traded furs.

The words around the shield say "CONCORDIA SALUS." This is a Latin phrase that means "salvation through harmony." It is the motto of both the city of Montreal and the Bank of Montreal. A ribbon with the name of the bank that made the token appears at the bottom of the coat of arms. At the top, it says "BANK TOKEN." At the bottom, it says "HALF PENNY" or "ONE PENNY," along with the year 1837.

Studying Habitant Tokens

Early Canadian coin expert Pierre-Napoléon Breton showed both the half penny and penny versions of these tokens in his book. His book, Illustrated History of Coins and Tokens Relating to Canada, came out in 1890. Even though there were four types of each token (one from each bank), Breton gave the same number to all pennies (521) and all half pennies (522). Later books sometimes add letters (like 521a, 521b) to show tokens from each different bank.

The first detailed study of these tokens was by Eugene Courteau. His book, The Habitant Tokens of Lower Canada (Province of Quebec), was published in 1927. He grouped the half pennies based on small details in the letters. For the pennies, he grouped them by whether the ground the habitant stood on was large or small. He described over 60 different kinds of habitant half pennies and over 50 kinds of pennies. More recent books list fewer main types, with about 9 for the half pennies and 13 for the pennies.