History of education in Chicago facts for kids

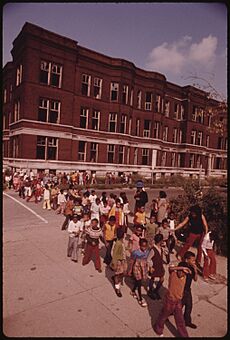

The history of schools in Chicago goes all the way back to the 1830s! This story covers all types of schools. It includes public schools, private schools, and religious schools. For more recent school history (since the 1970s), check out the Chicago Public Schools article.

Contents

Public Schools in Chicago

As Chicago grew in the late 1830s, the first small private schools opened. Eliza Chappell was likely Chicago's first public school teacher. Most early teachers were young men from New England.

These first schools were very basic. They had simple facilities. Only a small number of children could attend them. Even in the 1860s, one teacher might teach over a hundred students. These students ranged from 4 to 17 years old. School buildings were often just existing structures that were changed.

When Chicago became a city in 1837, people volunteered to check on the schools. But there wasn't much money for them. In 1845, an inspector said schools were crowded and poorly equipped. The first building made just for a public school was built in 1845. People made fun of it, calling it "Miltimore's Folly." This was after a teacher named Miltimore said it was needed.

In 1848, Mayor James Hutchinson Woodworth said Chicago urgently needed a better public school system. The city council agreed with him. The mayor had been a teacher himself. He wanted to attract good citizens to Chicago.

By 1850, less than one-fifth of children who could go to public school actually did. More children went to private or religious schools. Thousands of older children didn't go to school at all. Public school classes were still very large. Rooms were often not well kept. They also didn't have enough supplies. Parents who could afford it often hired private teachers.

Chicago's population grew quickly. Tens of thousands of new people arrived each year. They came from the East and from Europe. In 1835, the state government allowed public schools to be paid for by taxes. Chicago's city charter in 1837 made this even stronger.

Chicago quickly opened public elementary schools for grades 1-8. By 1848, there were 8 teachers and 818 students. John Clark Dore, a teacher from Boston, became Chicago's first school superintendent in 1854. At that time, there were 34 teachers and 3,000 students. When he left in 1856, student numbers had doubled to 6,100. Forty-six new teachers were hired. Four new schools were built, including the first high school.

Teachers' yearly salaries were $500 for men and $250 for women. To save money, schools started hiring young women. These women wanted to teach before they got married. They would then have to leave their jobs.

To train teachers, the city started "normal school" programs. These were two-year courses for students who finished 8th grade. The few new four-year high schools also offered two-year normal courses. For example, Ella Flagg Young's family moved to Chicago in 1858. In 1860, at age 15, she went to the Chicago Normal School. She graduated in 1862. She taught as an elementary teacher for three years. Instead of getting married, she chose a career in school leadership. In 1865, she became the director of a small "practice school" at Scammon School. This school helped train future teachers.

Progressive Education Ideas

Many important thinkers helped shape education in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Five of the most important were Francis Wayland Parker, John Dewey, Ella Flagg Young, Jane Addams, and William Wirt. All of them were in Chicago around 1900. They had many followers and greatly influenced what was called Progressive Education in Chicago. Because of them, Chicago played a big role in defining new ideas for schools across the country.

Francis Wayland Parker's Ideas

Francis Wayland Parker studied in Germany. He later became a school superintendent in Massachusetts. There, he created his Quincy Method. This method got rid of harsh rules and memorizing facts by heart. Instead, it focused on progressive ideas. These included group activities, teaching arts and sciences, and informal ways of learning. He did not like tests, grades, or ranking students.

As the principal of the Cook County Normal School in Chicago (1883–1899), he tried new ways to improve his teaching plans. For example, reading, spelling, and writing were combined into a new subject called "communication." Art and physical education were added to what students learned. He taught science by studying nature. In 1899, Parker started a private experimental school called the Chicago Institute. This school became the School of Education at the University of Chicago in 1901.

John Dewey's Influence

John Dewey wrote about many topics in philosophy. But he often returned to the idea of education in a perfect society. This was his main focus during his time at the University of Chicago (1894–1904). He worked there with Ella Flagg Young. He also started the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools. In these schools, his students and followers tested his ideas in real classrooms.

Ella Flagg Young's Leadership

Ella Flagg Young became the superintendent of Chicago Public Schools from 1909 to 1915. She put Dewey's progressive ideas into practice. She was the first woman to lead a large city school system. It had 290,000 students. The schools owned property worth $50,000,000. Her salary of $10,000 was the highest any woman had received in a government job in the U.S. She was also the first woman president of the National Education Association.

She was a professor of education at the University of Chicago (1899–1905). She became principal of the Chicago Normal School (1905–1909). She also served on the Illinois State Board of Education from 1888 to 1913. She wrote many books and articles about Dewey's ideas.

William Wirt and the Gary Plan

William Wirt was the superintendent in Gary, Indiana, a city close to Chicago. He became famous for his Gary Plan. This plan used a "two platoon system." This meant twice as many students could use the same school buildings. The schools were also expanded to include shops, labs, auditoriums, and playgrounds. Wirt learned Dewey's ideas when he was in graduate school in Chicago. He tried to use them in his schools.

Dewey and other educators praised this experiment. Businesses liked how it saved money. Even though labor unions had objections, Chicago started using the platoon system in some schools in the 1920s.

Chicago's new ideas about education influenced thinkers across the country. However, school superintendents and board members had to make daily decisions about school budgets. They often paid more attention to business ideas. These ideas focused on saving money and keeping taxes low. In expensive private schools, wealthy parents' wishes were very important. In these schools, the ideas of thinkers like Dewey were more popular.

Catholic Parochial Schools

By the 1920s, almost half of Chicago's population was Catholic. Many Catholic children, perhaps half, went to public schools. There was little risk of being taught Protestant ideas. This was because over a third of public school teachers were Catholic. Almost as many principals were Catholic too.

Catholic churches built their own schools. They used sisters (nuns) as teachers. Sisters had taken vows of poverty, so they were inexpensive teachers. German and Polish parents liked that these schools taught most classes in their own language.

Cardinal George Mundelein was the archbishop from 1915 to 1939. He took control of all the parish schools. His building committee decided where new schools would be built. His school board made rules for what was taught, what textbooks were used, and how teachers were trained. They also set up testing and school policies. At the same time, he gained influence in city government. A Catholic man named William J. Bogan became the Superintendent of public schools.

Schools During the Great Depression and War (1929–1945)

The Great Depression hit Chicago very hard. In 1932, 25% of people could not find jobs. The city's money dropped sharply. Teachers were paid with "script." These were notes the city promised to pay later. But the script quickly lost its value. By February 1933, public school teachers had not been paid for eight months.

New Deal programs helped people who were out of work. The WPA (Works Progress Administration) built 30 new schools for the city at no cost. The NYA ran its own high schools. The New Deal built many new school buildings. However, it did not directly pay for the public schools.

School programs were cut, especially the new junior college system. Teachers and staff lost their jobs. Salaries were lowered. Fewer students dropped out of school because they could not find jobs anyway.

In 1937, Chicago had a polio outbreak. The Chicago Board of Health ordered schools to close. This happened when the school year was supposed to start. The schools stayed closed for three weeks. Superintendent William Johnson and assistant superintendent Minnie Fallon found a way to teach elementary school students. They provided at-home distance education through radio broadcasts. This was the first time radio was used on a large scale for distance learning.

See also

- Chicago Public Schools

- List of colleges and universities in Chicago

- List of schools of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago

- University of Chicago Laboratory Schools

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |