History of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System facts for kids

The Cooperative Extension System helps people learn new ways to farm and improve their homes. It teaches useful skills and shares new discoveries from universities. This system has a long history, starting even before it was officially created.

In the late 1700s, after the American Revolution, some wealthy farmers started groups. They held meetings to share new farming tips. Sometimes, university professors even gave talks. This was like an early version of Cooperative Extension. By the 1850s, many schools held "farmer institutes," which were public meetings where experts discussed new farming ideas.

Contents

Starting Colleges for Agriculture

A big step for Cooperative Extension happened in 1862. The U.S. Congress passed a law called the Morrill Land-Grant College Act. President Abraham Lincoln signed it. This law gave each state land. States could then sell this land to create money for new colleges. These colleges would teach farming and other practical skills.

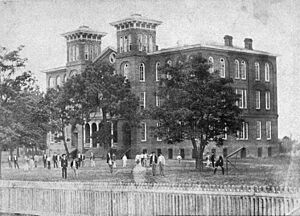

This act helped create the Agriculture and Mechanical College of Alabama in 1872. This college later became Auburn University. It faced money problems at first, but it eventually became the main place for Extension work in Alabama.

More Funding for Colleges

In 1890, a second Morrill Act was passed. This act gave steady money to these colleges. It also said that colleges receiving money could not treat people differently because of their race. However, states could get around this rule by setting up separate colleges for white and Black students. These separate Black agricultural schools became known as "1890 land-grant institutions."

The Huntsville Normal School (now Alabama A&M University) was the first Black school to become an 1890 institution in Alabama. It opened in 1875 and started getting money from the Second Morrill Act in 1891.

Challenges for Early Colleges

Even with these new laws, the land-grant college system faced problems. Colleges found it hard to create courses that students wanted, especially in the South. Many farmers were busy rebuilding their farms after the Civil War. Also, there was a lot of land available in the West, so farmers didn't always feel a need to learn new, intensive farming methods. Many college graduates also left farming instead of returning to their family farms.

The Need for Research and Sharing Knowledge

Many people realized that there wasn't enough good farming research. To fix this, Congress passed the Hatch Experiment Station Act in 1887. This law provided money for agricultural experiment stations in each state. These stations would do scientific research to improve farming.

However, the scientists at these stations soon saw a problem. Their new discoveries couldn't help farmers if farmers didn't know about them! They needed a way to share this knowledge.

J.F. Duggar, who ran the experiment station at API, and other professors felt it was important to reach farmers across the state. They wrote many letters to farmers, but this became too much work. They also knew that many farmers who needed help couldn't read or write. Some face-to-face meetings were happening, but they weren't enough.

Seaman Knapp: The "Father" of Extension

A man named Seaman Ashael Knapp (1831–1911) is often called the "father" of the Extension Service. He was a college teacher and leader who later became a farmer.

Knapp believed in "farm demonstrations." This meant showing farmers new methods directly on their own farms. He realized that farmers learned best by seeing things work for themselves.

His ideas became very important when the boll weevil pest attacked cotton fields in the South. This insect caused huge damage and scared many farmers. The government hired Knapp to help farmers fight the weevil. He sent agents to show farmers how to deal with the pest. By 1904, about 20 agents were working in Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas. This was a big step towards formal Extension work.

Tuskegee Institute's Role

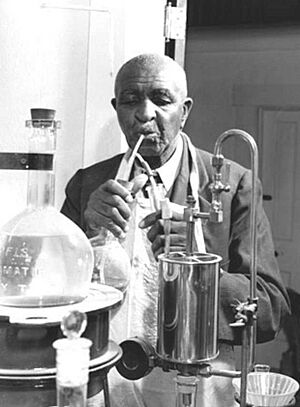

Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), a school for Black students, also played a huge part in starting Cooperative Extension work. Much credit goes to Booker T. Washington, who founded the institute, and to the famous agricultural scientist George Washington Carver.

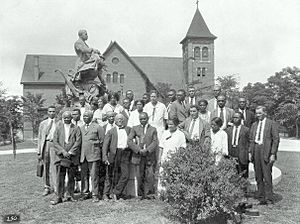

Booker T. Washington started the first Tuskegee Farmer Conference in 1892. About 500 people came. This conference is still held every year and was a major event for Black agricultural outreach.

Washington and Carver knew that new discoveries from Tuskegee and other research places needed to reach farmers.

Jesup Wagons: Mobile Classrooms

Tuskegee came up with a great idea: agricultural demonstration wagons, known as Jesup wagons. These were like mobile classrooms. They traveled to different parts of the state to teach farmers and sharecroppers new farming methods. George Washington Carver designed these wagons and chose the tools and lessons.

The wagons were so successful that the U.S. Department of Agriculture adopted them. Thomas Monroe Campbell, from Tuskegee Institute, became the nation's first Black extension agent in 1906. He operated the Jesup wagons under Carver's guidance. By 1925, there were 31 Black Extension agents working in 21 Alabama counties.

Formal Extension Work Begins

A big moment for formal Cooperative Extension in Alabama happened in 1906. Seaman Knapp started cooperative farm demonstration work. He oversaw this work nationally for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Agents were appointed to work with white farmers, and T.M. Campbell worked with Black farmers in Alabama, which was a segregated state at the time.

Three years later, Knapp made an agreement with API (Auburn University) and its Experiment Station. This agreement meant that Extension work in Alabama's public schools would be done together by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and API. This became a model for other states.

Luther Duncan, an API graduate, was chosen for this important role. By 1910, there were 37 agents working in 41 Alabama counties. Their salaries were often helped by county money, which became a common practice for Extension work.

Corn and Tomato Clubs

Duncan also helped organize Boys' Corn Clubs. These were early versions of 4-H clubs. The clubs taught farm boys new farming methods. A clever idea behind these clubs was that children were often more open to new ideas than their parents. When fathers saw their sons succeed with new techniques, they often adopted them too.

Similar success happened with Girls' Tomato Clubs, which started in 1911. Girls learned about growing tomatoes and food preservation, and their mothers often learned from them.

The Smith-Lever Act of 1914

In 1914, the important Smith-Lever Act was finally passed. This law provided federal money to states to create a network of county farm educators across the nation. States had to match these federal funds. The law said that all Extension work in a state would be done through the state's agricultural college. Each college also had to create a separate Extension division.

Alabama officially accepted this act in 1915. The Alabama Extension Service was organized under the direction of the Alabama Polytechnic Institute (Auburn University). J.F. Duggar led the new organization, and Luther Duncan became superintendent of Junior and Home Economics Extension.

The act initially gave $10,000 each year to agricultural colleges for agricultural and home economics outreach. This funding would increase each year if states matched the money.

Alabama Extension focused on four main areas:

- Farm demonstrations (showing farmers new methods).

- Woman's work (helping farm wives with food preservation and home improvements).

- Junior Extension (like Boys' Corn Clubs and Girls' Tomato Clubs).

- Specialist work (experts focusing on specific topics).

Even though the Smith-Lever Act put Tuskegee's Extension program under API's direction, it largely remained independent and led by African-Americans. Tuskegee did not receive 1890 funds until 1972, despite its early work.

Early Focus and Growth

The Alabama Extension Service first worked to improve the difficult economic situation of Alabama farmers. Many farmers grew cotton and faced the constant threat of the boll weevil. As more money became available, home demonstration agents were hired to help farm wives with things like food preservation.

Over time, Extension programs grew to include help with dairy farming, raising livestock, growing crops, gardening, selling farm products, and dealing with plant and animal diseases. Youth programs, like Boys and Girls Clubs, were also a key part of Extension work.

By 1914, 43 of Alabama's 67 counties had Extension agents. By the 1920s, many agents were college graduates and worked from fully equipped offices in many counties. More funding allowed Extension to hire specialists. These experts helped agents deliver programs. From these beginnings, Alabama Extension grew to have offices in all 67 counties.

Different Types of Extension Work

- Farm Demonstration: County agents helped farmers with agricultural development in their areas.

- Woman's Work: This work focused on women's needs, like canning and home improvements.

- Junior Extension: This included home economics and youth work, like the corn and pig clubs.

- Specialist Work: Experts focused on specific issues like dairy farming or preventing hog cholera. They held meetings, wrote to farmers, and developed new farming systems.

Movable Schools

Inspired by Tuskegee Institute, Alabama Extension sent specialists to "movable schools." These schools traveled to counties across the state to teach farmers.

Using Mass Media

Extension educators also started using mass media. They wrote short, timely articles about farming for local newspapers. The goal was to provide a column for every county newspaper each week.

Modern Technology in Extension

Alabama Extension has always used new technology to reach more people. As early as 1922, they used radio. By 1925, a powerful radio station called WAPI, "the Voice of Alabama," broadcast from the Auburn University campus. It shared news, weather, and educational programs about farming and homemaking.

Satellite and Video

In the late 1980s, Alabama Extension created a satellite network. Every county Extension office got a satellite receiver. This allowed them to receive educational programs from Auburn University. In the 1990s, they set up videoconferencing sites in county offices. This let people view educational programs over the internet.

Digital Tools and the Internet

Many Extension offices now have digital tools to quickly find plant diseases. The Alabama Cooperative Extension System website gets millions of visitors each year. Extension also uses web blogs to share news and information. They even stream interviews with experts online.

Virtual Extension

In recent years, the internet has changed how Extension shares information. This led to the idea of "Virtual Extension." This means that Extension's online presence, like its website, is becoming the main way people connect with them. Extension educators are learning to build relationships with people online through social media and blogs. This helps them reach even more people with valuable information.

|

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |