History of the cotton industry in Catalonia facts for kids

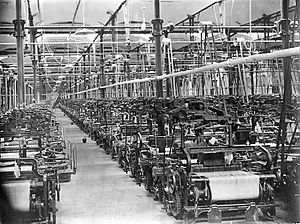

The cotton industry was very important in Catalonia, a region in Spain. It was the first and main industry that helped Catalonia become a major industrial area by the mid-1800s. This was special because most early industrial growth happened in northern Europe. Like many other countries, Catalonia's cotton industry was one of the first to use the factory system and new machines on a large scale.

The industry started in the early 1700s. At first, they made printed cloth called chintz (Catalan: indianes). The government encouraged this to reduce imports and to open up trade with the American colonies. Spinning cotton into yarn became important after new English technology arrived around 1800. The industry really grew in the 1830s when factories became common. This happened after Britain allowed skilled workers (1825) and machinery (1842) to leave the country.

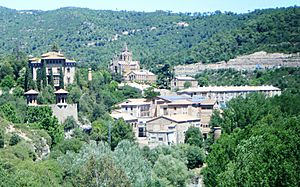

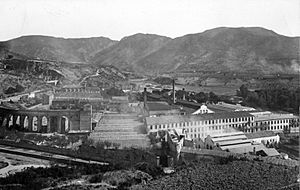

Factories first used steam power. But coal and steam engines were expensive to import. So, from the late 1860s, many factories started using water power from rivers. The government also encouraged building more than 75 industrial colonies (Catalan: colònies industrials). These were like small towns built around factories along rivers in rural Catalonia. They offered water power, cheaper workers, and land.

By the mid-1800s, the cotton industry needed more protection from foreign competition. Raw cotton, energy, and machines were more expensive in Spain. So, the industry mostly sold its products within Spain and to the remaining American colonies. The industry began to decline during the Great Depression. Spain faced many problems, including a struggling economy and a civil war. After 1939, a policy called "autarky" meant Spain tried to be self-sufficient. This cut the industry off from global growth and investment after World War II.

In the 1960s, Spain's economy opened up. But social changes caused the industrial colony system to fail. The oil crisis of the 1970s also hurt the industry. These events led to the end of the cotton industry as it was known.

However, the industry left behind amazing buildings. Cotton factory owners funded beautiful modernisme buildings. These included factories, homes, and apartment buildings. Often, these buildings were both company offices and symbols of the owner's power and modern ideas. Some famous examples are Casa Batllo, Casa Calvet, Casa Terradas, Casa Burés, and Fàbrica Casaramona. The Church of Colònia Güell is even a UNESCO World Heritage site! Older buildings from the mid-1800s include Palau Güell, Vapor Vell, Can Batlló, and the Aymerich factory in Terrassa. The Aymerich factory is now the National Museum of Science and Industry.

The industrial colonies helped modernize rural Catalonia. Many of their old buildings now house museums. Some of the old water turbines still make electricity for the national power grid. These colonies also attracted many workers, changing where people lived across the country. This still affects politics today.

Contents

History of Catalan Cotton

1650-1736: The Chintz Revolution Begins

The first printed cotton cloth, called chintz or calicoes (Catalan: indianes), arrived in Barcelona around 1650. It probably came from Marseilles, France. When calicoes arrived in Europe, they changed clothing forever. They were more comfortable, cleaner, cheaper, and came in amazing colors compared to silk and wool clothes. People quickly wanted more of them.

Spain, like England and France, tried to ban calico imports. First, in 1717, Asian textiles were banned. This was likely because merchants in Cádiz and Seville complained that these imports hurt their trade with Mexico.

Then, in 1728, Spain banned European copies of Asian textiles. This rule also aimed to encourage local weaving and printing. It allowed Malta's spun yarn to be imported and freed new businesses from old guild rules. The Spanish Crown did not directly invest in this industry like it did for wool. But supporting the cotton industry in this way was unique in Europe. It helped the Catalan cotton industry grow quickly and become very large.

1736-1783: Printing Chintz Grows

The first printing on linen cloth in Barcelona happened in 1736. They used wooden blocks or stamps to print designs. Smart merchants saw a market for these goods and started printing businesses. This focus on printing was different from England. England banned pure cotton cloth but not raw cotton. So, England became successful in spinning and weaving linen-cotton mixes.

In the early 1700s, linen cloth was imported from Amsterdam. In return, Spain sent brandy.

As demand for brandy and wine grew in northern Europe, this trade changed the whole Catalan economy. It especially helped the textile industry. First, growing grapes became very profitable. This wealth led to more demand for manufactured goods like printed cloth.

Second, the grape growing business created extra money. This money could be used to build ships and increase trade, especially with the American colonies. It also funded new businesses like printed cloth making. This trade grew quickly after the Cádiz monopoly was ended in the late 1700s. Wine, brandy, and printed cloth were exported. In return, they imported things needed for textiles, like indigo dye. Merchants also invested in other profitable trades, which helped fund the growing textile industry.

Printing grew fast in Barcelona. Spain was enjoying a time of rising population and wealth in the second half of the 1700s. Factories were built on the ground floors of buildings inside Barcelona's old city walls. Local craftspeople lived near the Sant Pere neighborhood. The Rec Comtal water source there had always been used for dyeing cloth and for drying it in fields. The number of printing shops grew from 8 in 1750 to 41 in 1770, and to over 100 in 1786. This was more than any other city in Europe! In Mataró, by the late 1740s, there were 11 businesses, about 470 looms, and 1300 workers.

The industry was strong in Barcelona because of skilled workers from medieval textile guilds. They learned new techniques from immigrants from Marseilles, Hamburg, and Switzerland. The Escola de Belles Arts (School of Fine Arts), founded in 1775, taught engraving and drawing. This training was very important for the industry's growth.

1783-1832: Early Industry Steps

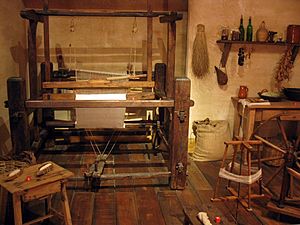

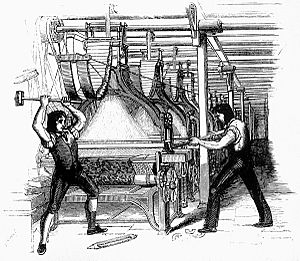

This time is called "proto-industrial" or "pre-industrial." It means that spinning and weaving slowly grew across Catalonia. People often worked from home, with merchants giving them materials and collecting finished goods. Around 1800, the first machines invented in England started to be used.

Wars in Europe and America between 1793 and 1814 stopped the fast growth of printed cloth and trade. The industry had to rely on the Spanish market. It also had to start spinning its own yarn (which wasn't a big part of the printing industry before) and use machines to make things faster.

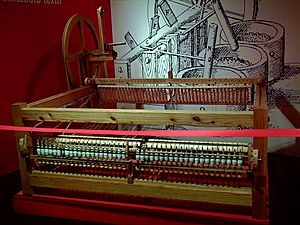

Cotton spinning and weaving began in the 1760s, but it used old hand methods. It didn't become a real industry until the 1790s. Most yarn came from Malta at that time. But when the English captured Malta, a royal rule in 1802 banned imported yarn. This forced the industry to spin its own cotton. Around 1806, it became easier to get French copies of the advanced English spinning mule machine. This was thanks to the Fontainebleau Pact.

New machines arrived in Catalonia over time. The first spinning jenny came in 1785 (21 years after it was invented). The first water frame arrived in 1793 (24 years after its invention). The first spinning mule came in 1806 (27 years after its invention). By 1820, cotton print production was back to 1792 levels, but now using local cotton yarn. By 1815, Barcelona had 40 mules and jennies. By 1829, it had 410 mules and 30 jennies.

Unlike printing, which stayed in Barcelona, spinning spread to other parts of Catalonia. This was partly because they needed water power. Igualada became the most important spinning center after Barcelona, followed by Manresa. Manresa had 11 water-powered spinning mills by 1831. Weaving spread even more widely. Mataro, Berga, Igualada, Reus, Vic, Manresa, Terrassa, and Valls were important weaving areas. But weaving was slower to use machines. By 1861, only 44% of weaving was done by machine.

Printing also improved during this time. The cylindrical printing process was introduced in 1817.

The wars between 1797 and 1814 also stopped the brandy trade with northern Europe. New competition from whisky and vodka also arose. So, merchants found a new market for brandy and wine in America. This encouraged them to import raw cotton as a return trade. This trade was still very profitable. It provided the money to buy spinning and weaving machines and the first steam engines.

The new machines needed more raw cotton. Trade with the American colonies began to import more and more cotton. Between 1804 and the late 1830s, the amount imported quadrupled to about 5 million kilograms. It first came from the American colonies, but after they became independent, it came from the United States and Brazil.

1832-1861: The Big Jump in Industry

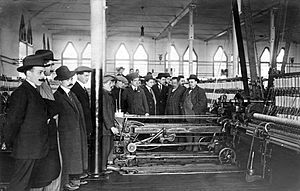

The industrial age truly began in 1833. That year, the first steam engine in Spain was installed at the new Bonaplata Factory. This was possible because Britain had removed rules against skilled workers leaving the country in 1825. Writers at the time called this an "industrial revolution." It was also the first time machines made of cast iron were used. The company was started by men from different parts of the industry: Bonaplata (who imported and made machines after visiting England), Rull (printing), and Vilaregut (spinning and weaving).

The Spanish Government supported the company. The factory received money, and all cotton imports were banned. They could also import some materials and equipment without paying taxes. In return, the company promised to make power looms and spinning machines for sale in Spain. They also agreed to let anyone who wanted to learn about steam technology visit their factory. This helped share new technology across the country.

This period saw a huge jump in industrial growth. Cotton spinning and weaving became mechanized at the same time that cast iron was first produced. Also, lands owned by the church were sold, which increased farm production. The population grew a lot too. People had more money from higher wages. Money also came back from the former colonies after they became independent. The factory system became common. Within a year of Bonaplata's factory opening, five more companies had raised money to import and install steam engines. When Britain removed rules on machine exports in 1842, British machine makers started selling a lot more abroad. By 1846, 80 steam engines were running in Spain.

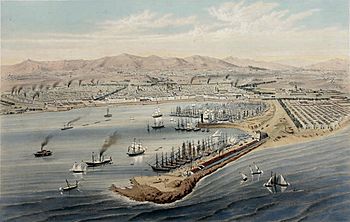

The number of ships carrying raw cotton to Barcelona soared. It went from 12 in 1827 to 65 in 1835, and to 140 in 1840. Most of this cotton came from Cuba and Puerto Rico. By 1860, 18,000 tons of cotton were imported, which was 10 times more than in 1820.

From the late 1830s, the industry grew too big for Barcelona's walled city. Steam engines often exploded, which scared people. So, factories started to be built in nearby villages like Gracia, Sant Andreu, Sant Martí, and Sants. These became new industrial areas long before they joined Greater Barcelona.

Industrialization made factories more productive and lowered prices. By 1861, most cotton factories did everything in one place: spinning, weaving, and finishing. This helped them save money and compete better internationally. In 1840, Spanish textiles were 81% more expensive than English ones. By 1860, machines had brought that down to 14%. The price of printed cotton in Catalonia dropped by 69% between 1831 and 1859. This pushed producers in other parts of Spain out of the market. For example, the price of linen cloth, mostly made in Galicia, did not change. So, the linen industry disappeared. At the same time, the cotton industry helped wool textile production grow in Sabadell, Tarrasa, and Manresa. This led to the decline of older wool centers in Castille.

Industrialization also caused social problems and disagreements. In 1835, the Bonaplata Factory was attacked and burned. In 1839, the first workers' union in Spain was formed, called the Association of Weavers of Barcelona. In 1842, there was a revolt in Barcelona. People were against the government's free market policies, which they felt threatened their jobs. Between 1849 and 1862, wages dropped by 11%. People spent 54% of their money just on food. Life expectancy was 50 years for salaried workers and 40 for day laborers. In 1854–1855, the Conflict of the selfactinas in Barcelona involved workers destroying machines. They were angry about new "self-acting" spinning machines that caused many workers to lose their jobs. They burned factories and demanded that the machines be removed, hours be reduced, and a minimum wage be set. This led to the first general strike in Spain.

Despite industrialization, the industry struggled to compete with foreign imports. It asked the government for protection through tariffs. A constant problem was the higher cost of raw materials and machinery. From 1830 to 1844, raw cotton cost 47% more in Barcelona than in New York, and 28% more than in Liverpool. Coal prices in Barcelona were 76% higher than in Britain. This was mostly due to shipping costs from Britain and taxes. Machines and parts also came from Britain and cost up to three times more for the same reasons. However, wages in Catalonia were about 15% cheaper than in Lancashire, England. Other problems included illegal goods entering the country. The Catalan cotton industry was also smaller and less productive than the British one. Without protection, it probably would have failed against British competition, just like Portugal's textile industry did. Because of this, future growth would only come from selling to a protected market within Spain.

1861-1882: The Rise of Industrial Colonies

Laws passed in the 1850s and 1860s helped the industry grow into rural Catalonia. This was because factories could lower their costs there.

The Agricultural Colonies Acts of 1855, 1866, and 1868 aimed to modernize farming areas. But industrial colonies could also benefit from these laws if they were built in rural areas. This meant they were free from industrial taxes for 10–25 years, and workers didn't have to do military service. Across Spain, 142 industrial colonies benefited. 26 of these were textile companies, and 15 of those were in the province of Barcelona. Most of these 26 factories did everything: spinning, weaving, and finishing cotton.

Also, the Water Acts of 1866 and 1879 allowed factories to use water as a free energy source. This saved money on importing English coal. It also meant businesses using water power didn't pay industrial taxes for ten years. About 17 Catalan industrial colonies used this law.

These two ideas, plus cheaper workers, land, and building materials outside Barcelona, led to many factories being built along rivers. This was perhaps the highest concentration in Europe. Even more colonies were built in the 1870s after the American Civil War ended. This made raw cotton available again. The many factories along the Ter and Llobregat rivers meant that railways could be built profitably. From about 1880, these railways connected local coal mines to industrial colonies (water power was not always reliable). They also lowered the cost of supplying cotton and bringing textiles to market.

In total, about 100 industrial colonies were built in Catalonia. 77 of these were textile factories, and most of them made cotton.

1882-1898: Protected Trade with the Colonies

As factories made more products than they could sell, the textile industry asked the government for more protection. The 1882 Commercial Relations with the Antilles Act made Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines like a special trading zone for Spain. This meant these American colonies had to buy Spanish products and couldn't buy cheaper foreign goods.

Spanish governments at this time favored protecting local industries. This united the interests of textiles, grain farmers, and the iron and steel industry. The 1891 Canovas Tariff went even further. One writer called it the first step towards the government getting more involved in business and rejecting competition. This eventually led to the "autarky" policy after 1939.

At that time, tariffs (taxes on imports) were the main way governments around the world made money. Protectionism was growing in Europe. In the US, a protectionist approach was common from after the Civil War until the 1930s. The 1894 US Wilson-Gorman Tariff put taxes on sugar from Cuba (Cuba's main export). It also canceled a trade agreement with Spain that had lowered taxes on food from the US to Cuba. Combined with Spain's trade rules, this quickly restarted the war for independence in Cuba. Spain soon lost its colonies and, with them, the cotton market.

1898-1930: Focusing Inwards

When Spain lost its American colonies, the Catalan textile industry was huge. In 1900, it made up 56.8% of all manufacturing in Catalonia and 82% of all textile production in Spain. At first, activity in the cotton industry dropped sharply until 1903. A general strike in 1902 also made things harder.

Despite these problems, the industry continued to grow for the first few decades of the 1900s. This was because Spain's national income grew, and the railway network expanded. Railways lowered costs for delivering products within Spain.

There were some small efforts to find new foreign markets. In the ten years leading up to 1913, exports grew by just over 5% each year. There was also a temporary boom during World War I, especially when supplying France.

However, several things stopped the industry from expanding to foreign markets. Policies that protected grain production from other parts of Spain increased shipping costs for Catalan goods in the Mediterranean. Also, Spain had chosen a different railway track width for military defense reasons. This later made it harder and more expensive to export goods.

Because the industry had been protected for so long, Catalan companies didn't have the sales and banking networks in foreign markets that they had at home. They were not willing to take risks abroad. They often ignored requests from foreign distributors or demanded conditions that made them completely uncompetitive. Instead, they saw foreign markets as a way to sell extra products when they made too much. So, they missed many chances to export and to learn how to improve their products or become more competitive.

Finally, the money policies of the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera from 1923 hurt all Spanish exports.

1930-1990: Decline and Change

The Great Depression and growing problems in Spain led to a sharp decline in the Spanish economy. Catalonia faced a period of slow growth and decay. World War II completely stopped the import of raw cotton from the Americas. After the Civil War, Spain's economic policy of "autarky" (being self-sufficient) cut off almost all international trade. This meant the industry fell behind in technology and management. It also missed out on global growth and new investments after World War II. Low wages and difficulty importing machines before 1959 meant the industry used old machines and was not very productive.

When Spain started to open its economy in the 1960s, the industry faced a very different world. It had to make big changes. The British cotton industry had already declined a lot between the world wars. In the US, new synthetic fibers like polyester (1950s), spandex (1959), and Kevlar (1965) were introduced. By 1968, synthetic fibers were used more than natural ones. Developing countries began to focus on making clothes as they industrialized. So, the industry in developed countries started using more machines and less labor. New machines like open-end spinning and shuttleless looms replaced older technology in the US. The European Commission also began to open its market to producers from developing countries.

The industrial colony system began to fall apart in the 1960s. This was because their businesses were often family-owned and not flexible. Also, social changes meant workers wanted to own appliances, cars, or their own homes. The influence of religion declined, and towns offered more opportunities. By the 1980s and 1990s, almost all the factories in these industrial colonies closed.

The government's 1969 Plan for the restructure of the cotton textile industry aimed to close weaker companies, get rid of old machines, and reduce the number of workers. Ideally, workers would move to new industries like cars, metal processing, plastics, and chemicals. The number of people working in the industry dropped from 228,000 in 1958 to 133,000 in 1978. The cotton industry faced a major crisis because of the global oil shock, which caused prices to rise. By 1980, it could not compete with either "cheap" countries (like Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania) or advanced countries with lower production costs and higher productivity (like Europe, the United States, and Japan). When Spain joined the EU in 1986, it led to even more changes. Today, the industry employs about 5,000 people.

The company La España Industrial shows the beginning and end of the industry. It was the first public company formed in Spain for cotton manufacturing. It was also the first to do spinning, weaving, and finishing all in one factory. It started in 1847, grew to 2,500 employees in the late 1800s, combined factories in the 1960s, and finally closed in 1981. Can Batlló stopped textile production in 1964, and Colònia Güell closed in 1973. Colònia Sedó, which was the largest industrial colony in Spain in the 1930s, closed in 1980.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la industria del algodón en Cataluña para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la industria del algodón en Cataluña para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |