Instructional scaffolding facts for kids

Instructional scaffolding is like having a helpful guide when you're learning something new. Imagine building a tall tower: you use scaffolding to support it as you go, and then you take it away once the tower is strong enough to stand on its own.

In learning, scaffolding means a teacher gives you just the right amount of help. This help is special for each student. It lets you learn in a way that focuses on you, the student, instead of just the teacher talking. This often helps you learn better and understand things more deeply.

Scaffolding gives you support when you first learn new concepts or skills. This support can be many things. It might be helpful resources, interesting tasks, or guides. It can also be advice on how to think and work with others. Teachers can use scaffolding by showing you how to do something, giving you tips, or coaching you along the way.

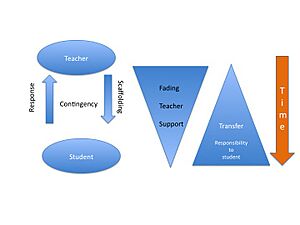

As you get better and can learn more on your own, the teacher slowly removes the support. This helps you become an independent learner. It also helps you develop your thinking, emotional, and physical learning skills. Teachers help you master a task or idea by giving support. This support can be outlines, recommended books, storyboards, or important questions.

Contents

What Makes Scaffolding Work?

There are three main things that make scaffolding helpful for learning.

Working Together

The first key part is that the learner and the expert (like a teacher) work together. This teamwork makes the learning strong.

Learning in Your "Zone"

The second part is that learning happens in your zone of proximal development. This is like a sweet spot where something is not too easy, but not too hard. To do this, the expert needs to know what you already understand. Then, they help you learn just a bit beyond that level.

Slowly Removing Support

The third part of scaffolding is that the help and guidance from the expert are slowly taken away. This happens as you get better at the task. Think of it like the scaffolding on a building. It gives "adjustable and temporary" support while the building is being made. The support for learners helps them understand and remember new knowledge. This help is slowly reduced until you can do the task all by yourself.

How to Make Scaffolding Effective

For scaffolding to work well, teachers need to think about a few things.

Choosing the Right Task

The learning task needs to make sure you use the skills you are trying to learn. The task should also be fun and interesting to keep you involved. It should not be too hard or too easy for you.

Guessing Possible Mistakes

After picking the task, the teacher tries to guess what mistakes you might make. Knowing these possible errors helps the teacher guide you away from wrong paths.

Using Scaffolds During Learning

Teachers apply different types of scaffolds while you are working on a task. These can be simple or change as you learn.

Thinking About Feelings

Scaffolding is not just about thinking skills. It also helps with your feelings. For example, if you get frustrated or lose interest during a task, the teacher (the expert) might help you manage those feelings. Encouragement is also a very important part of scaffolding.

The Idea Behind Scaffolding

The idea of scaffolding was first talked about in the late 1950s by Jerome Bruner. He was a cognitive psychologist who studied how people think. He used the term to describe how young children learn to speak. Parents help their young children when they first start talking. They create informal ways to help them learn. Bruner and his student Anat Ninio studied how parents help children learn by reading picture books together.

Scaffolding was inspired by Lev Vygotsky's idea. He believed that an expert helps someone who is new to a skill. Scaffolding means changing the amount of help to fit what a child can learn. During a lesson, a teacher can adjust how much guidance they give. More help is given when a child is struggling. Less help is given as the child gets better.

Ideally, scaffolding helps a child learn within their zone of proximal development (ZPD). This "zone" is the space between what you can do alone and what you can do with a little help. Language is very important for the ZPD and scaffolding. Vygotsky thought that language helps children grow their thinking skills. It gives purpose to what they do. Through talking, children can learn from others. This is a key tool in the ZPD.

When you talk with a skilled helper, your ideas become more organized. Studies show that scaffolding not only helps during a task but also helps your thinking development later on. For example, a study found that how much mothers talked and helped their 3- and 4-year-olds while playing was linked to the children's memory and language skills at age six. This shows that the quality of the scaffolding is important for learning.

A key idea for scaffolding is Vygotsky's zone of proximal development (ZPD). The ZPD is the gap between what you can do by yourself and what you can achieve with help from a knowledgeable friend or teacher. Vygotsky believed that children could learn any subject well using scaffolding within their ZPD. Learners are guided through activities that help them reach the next stage. This way, you build new understandings by using what you already know, with support from others who know more.

In learning to write, support usually comes from talking. A writing tutor helps you focus, makes the task easier, motivates you, points out important parts, helps with frustration, and shows you what to do. Through working together, the teacher guides the conversation to help you develop your own thinking. The adult handles parts of the task that are too hard for the child, while slowly expecting more from the child. Talking is a key tool for thinking and responding. It helps thinking become more abstract and flexible.

Vygotsky said, "what the child is able to do in collaboration today he will be able to do independently tomorrow."

Some important parts of scaffolding include being able to predict what will happen, having fun, focusing on meaning, sometimes switching roles, showing examples, and using clear names for things.

Types of Scaffolding in School

There are different ways scaffolding can be used in schools.

Soft and Hard Scaffolding

According to Saye and Brush, there are two levels of scaffolding: soft and hard.

- Soft scaffolding is when a teacher walks around the classroom and talks with students. The teacher might ask about their approach to a problem and give helpful feedback. This type of scaffolding depends on what students need at that moment. It can be hard to do this perfectly in a big class.

- Hard scaffolding is planned ahead of time. It helps students with tasks that are known to be difficult. For example, a math teacher might plan hints to help students discover a formula. In both cases, the teacher is the "expert" providing the scaffolding.

Learning from Each Other

Reciprocal scaffolding is when a group of two or more people work together. They learn from each other's experiences and knowledge. The scaffolding is shared and changes as the group works. Vygotsky believed students learn higher-level thinking skills when they work with an adult expert or a more capable friend.

Tech Help

Technical scaffolding is a newer way of scaffolding where computers act as guides. Students can get help from web links, online tutorials, or help pages. Educational software can help students follow a clear structure and plan their work.

Directive and Supportive Scaffolding

There are two main types of scaffolding in how teachers talk to students:

- Directive scaffolding is when teachers mostly give information and then check if students understood it. This can make learning passive, where students just try to remember what the teacher said.

- Supportive scaffolding is when teachers use student answers to explore ideas together. This makes the classroom talk more like a conversation. The teacher becomes more of a guide, allowing students to be active in creating meaning. This shows a shift in how the teacher sees their role, making supportive scaffolding more than just a teaching method.

How Guidance Helps

The help given to learners in scaffolding is called guidance. It comes in many forms, but it's always meant to help you learn better.

Guidance and Thinking Load

Giving guidance helps manage your cognitive load. This means it helps keep your brain from getting too overwhelmed with information. In scaffolding, you can only reach your learning goals if the amount of information you have to process is kept in check by good support.

Traditional teachers often give a lot of direct instructions, breaking down complex tasks into small pieces. This can sometimes make the thinking load higher for students.

Teachers who use a constructivist approach focus on guided discovery. They emphasize helping you use what you learn in new situations. These teachers give more guidance than direct instruction.

How Much Guidance?

Studies show that more guidance can help a lot with scaffolded learning. However, it doesn't always guarantee more learning. The quality of the guidance matters. Having different types of guidance, like examples and feedback, can help. But too much guidance, or guidance that isn't right for what you're learning, can actually make things harder. But when guidance is designed well and fits the learning, it's more helpful than less guidance.

When to Give Guidance

The timing of guidance is important.

- For some teaching styles, guidance is given right away, either at the start or when you make a mistake.

- For other styles, guidance might be delayed.

Some research suggests that immediate feedback on errors helps you learn quickly. The sooner you get feedback, the easier it is to use it. However, other studies show that waiting a bit before giving feedback can help you develop your own problem-solving skills and remember things better in the long run. So, immediate feedback helps solve problems faster, but delayed feedback can lead to better long-term learning.

Learning by Doing (Constructivism)

Constructivism is a way of thinking that believes you build your own knowledge from your experiences. It suggests that learning works best when you are given minimal guidance and figure things out for yourself. In this view, teachers should give you goals and just enough information and support when you ask for it. They believe that too much direct teaching of learning strategies can stop your natural way of remembering past experiences.

An example of this is in science class. Students might be asked to discover science rules by acting like researchers.

Direct Teaching (Instructionism)

Instructionism is a teaching style where the teacher is the main focus. It often involves the teacher giving information directly to students. This can mean lots of practice and memorization. The teacher plans and organizes the lesson carefully, making sure the information is clear. The main idea is that the teacher gives the instruction upfront.

Instructionism is often compared to constructivism. Both use guidance to help learning, but they differ in how much, when, and in what way they give that guidance. Direct instruction is an example of instructionism in the classroom.

Less Guidance in Education

Minimal guidance is a term for teaching methods like inquiry learning or project-based learning. The idea is that learners, no matter how much they know, learn best by discovering or figuring things out themselves. This is different from classrooms where the teacher leads everything.

In this approach, the teacher's role changes from being the "sage on the stage" to the "guide on the side." This means teachers might not answer questions directly. Instead, they might ask questions back to you to make you think more. This is like being a "facilitator of learning" instead of just giving out knowledge.

Minimal guidance can be a bit controversial. Some say it's not always effective for beginners because it doesn't match how our brains learn best. They argue that more guided approaches work better. However, some studies show that minimal guidance can work well in certain areas and situations, especially if you get enough chances to practice.

Criticisms of Minimal Guidance

One criticism of minimal guidance comes from cognitive load theory. This theory says that minimal guidance doesn't fit how our brains work, especially for new learners. It suggests that fully guided teaching methods are more efficient. Other criticisms say there isn't much proof that student-centered approaches are better than teacher-led ones, even though many big education groups support them.

More specific criticisms include:

- Minimal guidance is not as efficient as direct teaching because it lacks clear examples.

- It can lead to fewer chances for students to practice.

- In project-based learning, teachers might have too many projects to manage, leading to less guidance.

Finding a Balance

Many people are trying to find a way to combine minimal guidance and fully guided instruction. One idea is to change the teaching style based on how much the learner already knows. More experienced learners might need less direct instruction. For example, even cognitive load theory suggests that as learners become experts, they need less direct guidance.

Another idea is to use teaching methods from things like martial arts. These methods use direct instruction to help students discover things through repeated practice. The goal is to see instruction and discovery not as opposites, but as things that can work together.

How Scaffolding is Used

Instructional scaffolding can be seen as the ways a teacher helps you bridge a gap in your understanding or move forward in your learning. These strategies change as the teacher sees what you can do at first and then gives you feedback as you progress.

In the past, scaffolding was mostly done through talking in person. In classrooms, scaffolding can include:

- Showing how to do things (modeling).

- Coaching and giving hints.

- Thinking out loud.

- Talking with questions and answers.

- Planned and unplanned discussions.

- Other interactive help to bridge a learning gap.

This can also include older students helping younger ones. These helpful students are called MKOs, which stands for "More Knowledgeable Other." An MKO is someone who understands an idea better and can help close a learning gap. This includes teachers, parents, and even friends. MKOs are a key part of learning in the ZPD. An MKO helps a student with scaffolding, aiming for the student to eventually find the answer on their own.

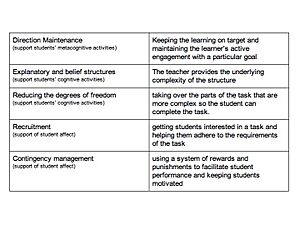

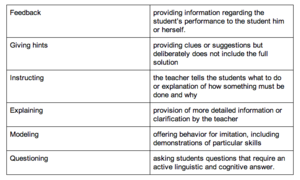

Teachers use many different scaffolding strategies. One way to look at them is through a framework that helps evaluate these strategies. This model looks at two parts of how an instructor uses scaffolding: their intentions and the ways they carry it out.

Scaffolding intentions: These groups show what the instructor hopes to achieve with scaffolding.

Scaffolding means: These groups show the different ways the instructor provides scaffolding.

Any mix of scaffolding means and intentions can be a scaffolding strategy. However, whether a teaching strategy is good scaffolding depends on how it's actually used. It's especially good if the help is given when needed and slowly removed as you learn.

Examples of scaffolding:

Teachers can use many types of scaffolds for different levels of knowledge. Depending on the learning situation (like if you're new to something or the task is complex), more than one strategy might be needed. Here are some common scaffolding strategies:

| Instructional scaffolds | What it is |

|---|---|

| Advanced organizers | Tools that show new information or ideas to learners.

These tools help organize information so you can understand new and complex topics. Examples are:

|

| Modelling | Teachers show the desired behavior, knowledge, or task to students.

Teachers use modeling to:

|

| Worked examples | A step-by-step demonstration of a complex problem or task..

These are often used in math and science classes and have three main parts: 1. Problem introduction: A rule or idea is explained. 2. Step-by-step example: An example is shown, demonstrating how to solve the problem. 3. Practice problems: One or more problems are given for you to practice the skill. |

| Concept Maps | Pictures that organize, show, and display how knowledge and ideas are connected.

Types of concept maps are:

|

| Explanations | Ways teachers present and explain new content to learners.

How new information is shown to you is very important for good teaching. Using things like pictures, graphic organizers, animated videos, audio files, and other tech can make explanations more fun and meaningful. |

| Handouts | Extra resources used to help teaching and learning.

These tools can give you the information you need (like ideas, task instructions, learning goals) and practice (like problems to solve). Handouts are helpful for explanations and worked examples. |

| Prompts | A physical or spoken hint to help you remember what you already know.

There are different types of prompts:

|

Scaffolding with Technology

When students are not in the classroom, teachers need to change how they scaffold. It can be tricky to adjust verbal and visual help to create a good learning environment for online learning.

Technology in education has grown a lot. Now we have AI-based methods, online learning environments, and more. This makes teachers think differently about scaffolding.

A recent review found four main types of scaffolding used in online learning:

- Conceptual scaffolding: Helps students decide what to focus on and guides them to key ideas.

- Procedural scaffolding: Helps students use the right tools and resources well.

- Strategic scaffolding: Helps students find different ways to solve hard problems.

- Metacognitive scaffolding: Encourages students to think about what they are learning and helps them reflect on it (self-assessment). This is a common area of research and helps with higher-level thinking and planning.

These four types help support students learning online. Other types of support mentioned by researchers include technical help, content help, and questioning.

As technology changes, so does the support for online learners. Teachers have the challenge of adapting scaffolding techniques, but also the advantage of using new web tools like wikis and blogs to support and talk with students.

Benefits in Online Learning

Studies show that when students learn complex topics online without scaffolding, they struggle to manage their learning. They also don't fully understand the topic. Because of this, researchers now stress how important it is to include conceptual, procedural, strategic, and metacognitive scaffolding in online learning.

Recent research also shows:

- Scaffolding can help in group discussions. In one study, groups with scaffolding participated more actively and had more meaningful talks.

- Metacognitive scaffolding can encourage students to reflect and help build a sense of community among learners.

Challenges in Online Learning

For scaffolding to work well online, many things are needed. These include knowing how to use technology, social interactions, and students' own motivation to learn. Working together is key for instructional scaffolding. This can be lost if the teacher doesn't create and start an online social space.

When teachers create a positive social space online, students feel more confident about understanding the course content and goals. If a teacher doesn't do this, students miss out on critical thinking, evaluating material, and working with classmates to learn.

Because online learning is often done at a distance, self-regulation is very important for scaffolding to work. One study showed that students who put things off (procrastinators) had a harder time with online learning and couldn't be scaffolded as well as in a face-to-face class.

Students who wanted to master the content more than get high grades were more successful in online courses.

See also

In Spanish: Andamiaje para niños

In Spanish: Andamiaje para niños

- Collaborative learning

- Constructive alignment

- Educational psychology

- Metacognition

- Social constructionism

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |