Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck Program facts for kids

The Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck (often called Crosscheck) was a special database in the United States. It collected information about people who had signed up to vote from many different states. The main goal was to find voters who might have registered or voted in more than one state.

Crosscheck was started in 2005 by the Kansas Secretary of State with help from Iowa, Missouri, and Nebraska. In December 2019, the program was stopped for good. This happened because of a lawsuit from the American Civil Liberties Union of Kansas. Before it was stopped, many states had already left the program. They said the information was not correct and that it put voters' private details at risk. Some also said Crosscheck unfairly removed voters, especially people from certain groups.

Contents

How Crosscheck Started

Crosscheck began in December 2005. The office of the Kansas Secretary of State worked with Iowa, Missouri, and Nebraska to create it. The program combined each state's voter lists into one big database. It tried to find possible duplicate registrations by checking people's first name, last name, and full date of birth.

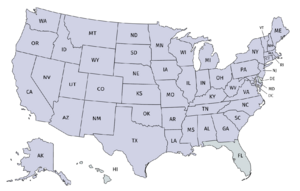

The first Crosscheck check happened in 2006 with voter records from Kansas, Iowa, Missouri, and Nebraska. By 2017, the last time Crosscheck was used, it included records from 28 states. The Kansas Secretary of State's office managed the program and offered it for free to all states that joined.

Under the Kansas Secretary of State at the time, Kris Kobach, the program grew quickly. It went from 13 states in 2010 to a high of 29 states in 2014. In 2017, Crosscheck looked at 98 million voter records from 28 states. It found 7.2 million "potential duplicate registrant" records, meaning people who might have signed up more than once.

Was Crosscheck Accurate?

Crosscheck marked two voter registrations as possible duplicates if they had the same first name, last name, and full date of birth. This happened even if the last four digits of their Social Security Number (SSN4) did not match, or if one or both SSN4s were missing.

Experts said that matching only by first name, last name, and date of birth often leads to many mistakes, especially for common names. This is because many different people can have the same common name and birth date.

Crosscheck's way of matching led to many "false positives." These are cases where two records were flagged as a match, but they were actually different people. For example, Virginia's 2013 report showed that 75% of Crosscheck's matches were false positives.

When a voter was wrongly identified, their private information was shared with other states. There was also a risk that they could be wrongly removed from the voter list. In Ada County, Idaho, election officials used Crosscheck's list and mistakenly removed 766 voters. None of these people were actually duplicate registrants.

To avoid removing eligible voters, states had to spend a lot of time checking each Crosscheck record. New Hampshire reported that it took 817 hours of work over almost a year to check their 2017 Crosscheck results. Even after all that work, they found no proof of many people voting twice. Virginia also said that while Crosscheck was "free," it needed "significant agency handling" because of all the false matches.

Before the program was stopped, 12 states had already left it. These included Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Washington.

In 2014, Crosscheck flagged over seven million "potential double registrants." However, fewer than four people were actually charged with voting more than once, and none of these cases led to a conviction. This made many people question how useful the system really was.

Concerns About Fairness

The way Crosscheck matched names also raised worries about fairness. Some studies suggested that the loose matching standards could unfairly affect certain groups of voters. For example, "Health of State Democracies" noted that 50% of people from certain ethnic groups share common last names, compared to only 30% of white people. This meant that Crosscheck's flagged lists had more African American, Hispanic, and Asian voters than white voters, compared to their actual numbers in the population.

Investigative reporter Greg Palast looked at the "potential duplicate registrant" lists. He claimed that Crosscheck unfairly targeted young, Black, Hispanic, and Asian-American voters. He believed this was done to help one political party win elections. Palast said that removing voters based only on similar names had a "built-in racial bias." This especially affected minority voters who often have a smaller pool of common names, like Hispanic voters named Jose Garcia.

However, being on the "potential duplicate registrant" list did not mean a voter was automatically removed. Independent investigations found that most states did not use these lists to remove voters.

Data Security Issues

In 2017, news reports from ProPublica and Gizmodo revealed serious problems with how the Kansas-managed database handled private voter data. The security was so weak that it could be easily accessed by someone with basic computer skills. Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach at first said there wasn't a problem but later promised to fix the security issues.

After talking with the Division of Homeland Security, Kobach quietly stopped Crosscheck for 2018. His replacement, Kansas Secretary of State Scott Schwab, later settled a lawsuit with the ACLU of Kansas. The lawsuit claimed that the state's careless handling of Crosscheck data broke people's right to privacy.

As part of the settlement, Schwab admitted there were errors in handling voters' private data. Kansas agreed to stop the program until very strict data security rules are put in place.

How Useful Was Crosscheck?

Crosscheck was often said to be a very important tool to stop voter fraud. However, critics argued that Crosscheck was only useful for a very specific type of fraud: someone voting twice across state lines, and only during general elections.

Crosscheck could not find:

- Someone voting twice within the same state.

- Someone voting twice in a primary election.

- Someone voting using the name of a person who had died.

Besides the problem of "false positives" (wrong matches), Crosscheck also had "false negatives." This means it failed to find voters who were registered in two states if their name had even a small difference. For example, "Vic Miller" registered in Kansas would not be seen as the same person as "Victor Miller" registered in Missouri, even if they had the same birth date and last four Social Security Number digits.

Voter List Maintenance

The discussion about Crosscheck is part of a bigger debate. This debate is about whether voter registration programs are a good way to prevent fraud.

A 2018 study by researchers from several universities looked at how removing a likely duplicate registration using Crosscheck affected voter access and election fairness. Their study of Crosscheck results from Iowa in 2012 and 2014 suggested that for every one double vote prevented, using Crosscheck's method might stop about 300 eligible people from voting. This was even in a "best practices" situation where all the false matches had been removed. The study authors said that election officials should think carefully about balancing making it easy for all eligible people to vote and preventing fraud.

Images for kids

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |