Jim Crow economy facts for kids

The Jim Crow economy describes the economic situation in the United States when Jim Crow laws forced racial segregation. These laws made Black people and white people live separately. Even though the laws focused on politics and legal rights, they also had a huge impact on how people earned money and owned property.

This term includes effects that were planned by the laws, effects that happened even if not written in the laws, and effects that continued long after the laws were removed. Some of these economic problems still affect people today. The Jim Crow economy was different from something like apartheid because it claimed everyone had equal chances, especially with land and jobs. But in reality, this was often not true.

Contents

What is the Jim Crow Economy?

The phrase "Jim Crow economy" helps us understand how money and jobs were affected during the time of Jim Crow laws. These laws often didn't mention race directly when it came to money. But they were enforced in ways that created huge inequalities.

The economic effects of Jim Crow are also linked to big changes in the U.S. economy from the Civil War through the 1900s. Social trends often led to new policies, which then caused economic changes. This topic covers many areas, like taxi drivers in the 1800s or domestic workers after World War II.

How the Jim Crow Economy Developed

After the Civil War: Reconstruction

After the Civil War, formerly enslaved people, known as freedmen, started to gain more political power, own land, and build wealth. But these gains were short-lived. The government's focus shifted from punishing those who left the Union to bringing them back.

In the decades that followed, Black people in the South lost political rights. It became harder for them to get new land. The Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 officially started the Jim Crow era. This ruling said "separate but equal" was legal, even though it was rarely equal.

A Time of Stagnation

By the early 1900s, progress for Black Americans had stopped and even gone backward. Around World War I, the South's farming economy struggled. It slowly began to shift towards cities and factories. This period also saw the start of the Great Migration, where many Black people moved from the South to Northern cities.

In the 1930s, more cities and factories grew in the South. Government programs like the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act tried to make the South's economy more equal to the rest of the nation.

The Aftermath of Jim Crow

By the time the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, the idea that one race was better than another (called scientific racism) had been disproven. The South had also caught up economically with the rest of the U.S. America was now mostly urban and industrial.

However, the economic progress Black Americans had made after the Civil War was largely reversed in the first half of the 20th century. Even though laws now guaranteed equality, it didn't automatically mean equal conditions in daily life. The shift from farming to city jobs didn't necessarily improve land ownership or job chances for Black Americans.

To truly understand the Jim Crow economy, we must look at the social and political situation before the laws were made. We also need to see how economic problems continued to affect people's lives even after the laws were gone.

Land Ownership for Black Americans

After the Civil War, Black Americans steadily gained ownership of farmland in the South. In 1875, they owned about 3 million acres. This grew to 12.8 million acres by 1910. Some estimates suggest total Black land ownership in the South reached 15 million acres within 50 years after slavery ended.

However, there were also problems. Some property was taken illegally. For example, 24,000 acres were taken from 406 Black landowners in the early 1900s. By 1930, the number of Black-owned farms was 3% lower than it had been at the start of the century.

Rural Land Ownership

After gaining freedom, Black Americans could get land in the South in two main ways. They could buy it from private owners. Or they could claim public land offered by the government, like through the Southern Homestead Act of 1866.

The Southern Homestead Act opened up public land in states like Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi. It hoped to give land to freedmen by limiting claims to 80 acres for the first two years. But not as many people bought land as hoped. Many newly freed slaves didn't have the money to develop undeveloped property. Only 4,000 of 11,633 total claims were made by freedmen.

The Southern Homestead Act was seen as a punishment by some in the South. It was canceled in 1876. After it was repealed, public lands were sold again to large buyers. Before the Act was reversed again in 1888, over 5.5 million acres in five Southern states were sold to land speculators and timber companies.

South Carolina's Land Commission was a special case. It was a state group formed after the Civil War to buy large farms and sell the land to small farmers. These farmers could pay back the cost over 10 years. From 1868 to 1879, the Land Commission sold farmland to 14,000 Black families.

In Georgia, Black property owners gained about 10,000 acres of land after the Civil War. But on average, Black Americans in Georgia had very little wealth, less than $1 per person. Between 1880 and 1910, their average wealth grew to $26.59 per person. However, this was still only 2% to 6% of the total wealth held by white Georgians.

By 1910, in 16 Southern states, there were 175,000 Black farm owners compared to 1.15 million white farm owners. In most of these states, the average white-owned farm was nearly twice the size of the average Black-owned farm.

Land ownership was important for both groups. But Black landowners often couldn't use their land as productively as white landowners. White landowners could get credit directly from Northern banks because they had more land. This helped them control the cotton trade.

A study of cotton farms in the late 1800s showed that white owners could leave more land unplanted to rest. They also had almost twice the value in farming tools. And they were more likely to have access to fertilizer than Black landowners. This meant Black Americans worked harder for less crop return. They also put the long-term health of their land at greater risk.

Between 1900 and 1930, 4.7% of Black farm owners in the South became tenant farmers (farmers who rent land). While 9.5% of white farmers also became tenants, only 46.6% of all white farmers were tenants, compared to 79.3% of all Black farmers. It was also harder for Black people to buy land. White owners often refused to sell land to Black buyers, no matter the price. There was little legal help if property was lost due to unfair practices.

Money for loans was also hard to get. Banks like the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company failed. Lending groups started by charities often couldn't handle even small loan defaults. Banks outside the South were often unwilling to lend money for Black land purchases. They worried that a class of Black landowners would lead to more demands from Northern factory workers.

With new land hard to get, and existing land only able to be divided so much, younger generations were pressured to move to Southern cities or out of the South entirely. When the U.S. entered World War I, Northern cities became a major destination. Northern factories hired many former farmers. The South industrialized much slower. In areas where white landowners kept large farms and many Black laborers remained, farming stayed the main economic activity.

Urban Land Ownership

Black Americans started moving into cities right after the Civil War. By 1870, the Black population in cities over 4,000 people increased by 80%. This was much higher than the 13% increase in the white population. Unlike before the war, cities that grew after the war tended to be much more segregated.

For example, in Georgia, Black Americans' urban property value increased from $1.2 million in 1880 to $8.8 million in 1910. These properties were often in the least desirable areas. After World War I, much of this property was sold to white buyers as Black Americans moved to Northern cities in large numbers.

Before 1910, there were no official racial zoning laws in Southern cities. However, real estate developers often refused to sell to Black buyers outside of specific areas. The National Association of Realtors could even punish a realtor for selling property to someone of a different race than those already living in a neighborhood. This had the biggest impact on those who moved to cities early on. For those who moved North after 1965, they often found neighborhoods that were less segregated.

The early pattern was for existing Black neighborhoods to become very crowded. Property owners would then divide land in low-lying areas or near factories for unskilled workers. Starting with Baltimore in 1910, many Southern cities began to use racial zoning codes. Even though the Supreme Court overturned these in 1917, many cities simply changed their zoning to be based on who already lived in a neighborhood. Birmingham, Alabama, even illegally enforced a racial zoning code until 1951.

Many growing cities created their own Jim Crow rules. As they grew, they planned low-cost housing in areas with less access to public services. They often used roads or natural features as dividing lines. This practice wasn't only in the South. For example, in 1940s Detroit, a 6-foot-high concrete wall was built to separate a Black neighborhood from white developments. These policies affected not just the poor. Around 1950, a housing development near Stanford University limited non-white residents to 10% to keep their mortgage financing.

People and Migration

Southern Labor Force

In 1870, most Black Americans (85.3%) lived in the South. By 1950, this number dropped to 61.5%. By 1990, it was down to 46.2% living in Southern states.

In 1900, Black Americans made up 34.3% of the South's population. By 1960, this dropped to 21%. Within the South, the Black urban population grew from 8.8% in 1870 to 19.7% in 1910. For the entire United States, the Black population went from 79% rural in 1910 to 85% urban in 1980.

The Great Migration

From 1870 to 1880, white and Black people left the South at similar rates. But in later decades, Black out-migration slowed compared to whites in some states. However, during World War I, both groups left the South, with whites leaving slightly more. During World War II, the South lost 1.58 million Black people and 866,000 white people.

From 1950 to 1960, 1.2 million Black people left the South, compared to 234,000 white people. But from 1960 to 1970, the trend changed. The South still lost 1.38 million Black people, but gained 1.8 million white people. Starting in the 1970s, both groups moved into the South, but many more white people moved in.

These numbers hide some important facts. The average education level of Black Americans leaving the South was low. At the same time, many white men with college degrees in the South were born outside the region. Also, Black Americans often moved into areas where Black unemployment was very high (up to 40%). There were also few jobs for unskilled workers in these areas.

Labor and Work

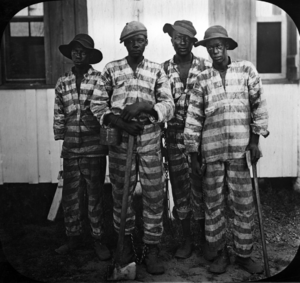

Convict Leasing

Convict leasing was a system where people convicted of crimes had their labor sold to employers by the prison system. The employer gained control over the prisoner. They often cared little for the prisoner's well-being beyond the lease term. This was similar to debt peonage, where workers had little say in when their debt was considered paid.

Economic Coercion

During the Civil Rights Movement, "economic coercion" was used to stop Black people from participating. This meant denying them credit, evicting them from their homes, and canceling their insurance policies. In 1973, only 2.25% of 5 million U.S. businesses were owned by Black Americans. Most of these businesses were very small.

Some people saw Black communities as "internal colonies" within the country. This idea suggests that Black-owned businesses were like a "ghetto domestic sector." White-owned businesses operating in these communities were an "enclave sector." And Black laborers working outside the community were a "labor-export sector." The Jim Crow era ended not only because of the Civil Rights Movement but also due to pressure from other countries.

Labor Roles and Farming

Laws about contracts, enticing workers, vagrancy (being jobless), and debt peonage helped keep workers in place and limited competition. This was important in a system where farming needed a lot of workers. The South's economy was mostly based on farming for many years. Factories only started growing significantly in the 1930s.

For those who didn't own farmland, the main jobs were farm laborer, sharecropper, share-renter, and fixed renter. Some large landowners paid set wages, but this was hard because there were few banks in the South. Paying a set wage meant risking overpaying when labor was not needed, or losing workers during harvest time.

So, the common practice was to contract labor for an entire season. Since there wasn't much cash, this led to sharecropping. Sharecroppers received a part of the profits from selling crops at the end of the season. Share-renters paid a part of their crops as rent.

Whether white or Black, tenant farmers earned similar wages. Both the tenant and the landowner shared the risks of uncertain crop production. By the late 1800s, landowners had recovered enough from the Civil War to take on the role of merchants themselves.

As landowners became powerful again, the middle class in both rural and urban areas lost power. Poor tenant farmers were divided by race. This is when Jim Crow laws started to appear. They were a way to create divisions among the lowest social class by using obvious physical differences.

Labor Laws and Fairness

Even laws that didn't specifically mention race were often enforced unfairly against Black Americans. "Enticement laws" and "emigrant agent laws" aimed to keep workers from leaving. Enticement laws limited competition between landowners for workers. Emigrant agent laws stopped employers from trying to lure workers out of the region.

Contract enforcement laws were supposed to apply if someone intended to cheat. But often, simply failing to meet contract terms was treated as intentional. Vagrancy laws kept people from leaving the workforce entirely. They were used to force every able-bodied person to work. Sometimes, Black Americans were charged with vagrancy just for traveling outside their known area. Black Americans also struggled to get work contracts outside their home areas. Employers didn't want to pay to check their skills or knowledge.

Urban Labor and Industry

The economy shifted from farming to urban, industrial work. In the South, industrial growth began with jobs that needed a lot of workers but not much skill. For example, factory jobs increased from 14.5% in 1930 to 21.3% in 1960.

For Black men in the South, farming jobs dropped from 43.6% in 1940 to 4.9% in 1980. During the same time, factory jobs rose from 14.2% to 26.9%. Black women were also pressured to work outside the home, often in low-paying domestic service jobs. For example, in the late 1930s, female domestic workers earned only $3–8 per week.

For Black women across the South, factory jobs rose from 3.5% in 1940 to 17.2% in 1980. Personal service jobs decreased from 65.8% to 13.7%. One study from 1920 to 1930 found that Black men were losing non-farming jobs not to machines, but to white men.

Money and Finances

Insurance and Race

One major way wealth is passed down is through inheritance. Race-based life insurance rates started in the 1880s. Black clients faced higher rates, fewer benefits, and insurance agents didn't earn commission on their policies. When states passed laws against race-based rates, companies simply stopped selling insurance to Black clients in those states.

If customers with existing policies tried to buy more coverage, they were told they had to travel to a regional office. From 1896, "scientific racism" was used to claim Black clients were higher risks. This also made it hard for Black-owned insurance companies to get money to offer their own policies.

By 1970, remaining Black-owned insurance companies were targeted for takeover by white companies. These larger companies hoped to increase their number of Black employees by buying smaller firms. Even in the early 2000s, major insurance companies were still settling lawsuits from policyholders who bought policies during the Jim Crow era.

Property Inheritance Issues

Another economic impact happens when someone dies without a will. Land is then left to multiple people as "tenancies in common." Often, the people who inherit don't realize that if one owner wants to sell their share, the entire property can be forced into a "partition sale."

Most state laws prefer dividing the property fairly among owners. But many courts choose to force a sale because the land is worth more as one piece. Also, rural land is more useful as a single productive unit. This means a land developer can buy one person's share of a shared property. Then, they can use their position to force a sale of the entire property.

So, someone who inherits a share of property they don't use might sell it, thinking they are only selling their part. But they could accidentally cause other inheritors, who actually live on the property, to lose their homes. Black Americans in rural, poor areas often do not have detailed estate plans. Developers are known to target properties in these areas.

The Legacy of Jim Crow

Lasting Racial Inequality

Even if formerly enslaved people had received the "forty acres and a mule" promised after the Civil War, it might not have been enough to close the wealth gap between white and Black people. In 1984, the average wealth for Black households was $3,000, compared to $39,000 for white households. By 1993, the average wealth for Black households was $4,418, compared to $45,740 for white households.

In 1920, there were 925,708 Black farmers (owners and tenants). In 2000, there were only about 18,000 Black farmers. This is even less than the number of Black farm owners in 1870. Recent court cases, like Pigford v. Glickman, show that there are still racial biases in how government groups, like the United States Department of Agriculture, give out farm loans.

Local committees that decide on loans must be elected from current farm owners. In some cases, county commissioners were found to have unfairly denied disaster help to Black farmers. Black farmers trying to get loans to buy land also faced delays, while white borrowers received funding.

Unofficial Racial Segregation

The concentration of Black Americans in specific neighborhoods, which started after the Civil War and during the Great Migration, still negatively affects job rates. In fact, "one third of African Americans live in areas so intensely segregated that they are almost completely isolated from other groups."

The negative effects of this residential segregation on unemployment are twice as bad in large cities with over 1 million people. If residential segregation were reduced, unemployment could drop significantly. For example, if segregation were completely eliminated, unemployment could be cut by almost half for high school educated men, and nearly two-thirds for college educated men and women.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |