John Keats's 1819 odes facts for kids

In 1819, John Keats, a famous English poet, wrote six special poems called odes. These poems are some of his most well-known works. He wrote five of them – "Ode on a Grecian Urn", "Ode on Indolence", "Ode on Melancholy", "Ode to a Nightingale", and "Ode to Psyche" – very quickly in the spring. He wrote "To Autumn" later in September. Even though we don't know the exact order he wrote them in, some people think they fit together like a story. These odes were Keats's way of creating a new kind of short, lyrical poem, and they inspired many poets who came after him.

Contents

Keats's Life and Poetry in 1819

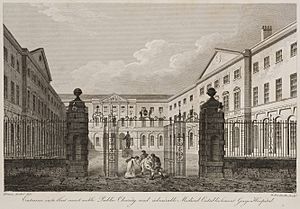

At the start of 1819, John Keats decided to leave his job at Guy's Hospital in London. He was an assistant surgeon, but the job didn't pay well. He wanted to spend all his time writing poetry. Before this, his brother George had sometimes helped him with money. But now, George needed help, and Keats didn't have any money to give. This made him feel very guilty and sad.

He thought about giving up poetry for a job that paid more. But first, he decided to allow himself a few months to write as much poetry as he wanted.

During the spring of 1819, Keats wrote many of his most important odes. After May 1819, he started working on other types of writing, like a play and some longer poems. He even went back to an unfinished epic poem called Hyperion. His brother's money problems continued to worry him. Because of this, Keats didn't have much energy or desire to write. However, on September 19, 1819, he managed to write To Autumn. This was his last major work and marked the end of his time as a very active poet.

How Keats Structured His Odes

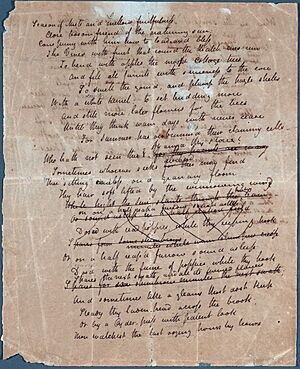

After writing "Ode to Psyche," Keats sent the poem to his brother. He explained that he was trying to find a better way to write an ode, different from the usual Sonnet style. He felt the traditional sonnet didn't sound right in English. He wanted a form that felt less sad and didn't end with a rhyming couplet (two lines that rhyme) that often didn't sound good. He wasn't sure if he had succeeded, but he hoped the poem would show what he meant.

Keats liked this new ode form because it was challenging. It pushed him to be a better writer. It also gave him a chance to write with strong feelings and clear descriptions, like he had started to do in his poem Hyperion.

In "Ode to Psyche," Keats used a story-like structure. He would set the scene, give some background, and then end with a conclusion. In his later odes, he stopped using a long introduction. The setting also became less detailed, sometimes just hinted at.

The Six Famous Odes

We don't know the exact order Keats wrote all six of his 1819 odes. We also don't know the best order to read them to understand their meaning. But "Ode to Psyche" was probably the first, and "To Autumn" was definitely the last. Keats simply wrote "May 1819" on the others. However, he worked on the spring poems together, and they connect to each other in their structure.

Ode on a Grecian Urn

"Ode on a Grecian Urn" is a lyrical ode with five stanzas, each having 10 lines. The poem starts with the speaker talking to an old urn, calling it a "still unravished bride of quietness!" This begins a conversation between the poet and the urn. The poet also calls the urn a "foster-child of silence and slow time." This means the urn is a quiet object that doesn't change over time.

In the first two stanzas, the poet talks to the urn as one whole object. He often mentions its silence, talking about "unheard melodies" that are sweeter than music we can hear. The poem then shifts focus to the people shown on the urn. There are two lovers who can't kiss but also never grow old. The poet notes that the urn's images never fade. He compares the urn to a silent bride and a foster child. In the second stanza, he talks about how unheard music is sweeter. In the third, fourth, and fifth stanzas, he describes what he sees painted on the urn.

Towards the end, the poet talks to the urn again. His tone becomes sharper as he looks for answers the urn can't give. In the very last two lines, the urn seems to say something important: "Beauty is truth—truth beauty / that is all ye know on earth and all ye need to know." These lines have made many people wonder what Keats truly meant.

Ode on Indolence

"Ode on Indolence" has six stanzas, each with ten lines. The poem is about a lazy morning for the person telling the story. During this time, three figures appear in a vision and capture his attention. The poem starts with a quote from the Bible (Matthew 6:28). This quote talks about how God takes care of the lilies in the field without them having to work. This introduces the idea of being lazy or "indolent."

The three figures wear "placid sandals" and "white robes." This reminds us of ancient Greek stories, which often appear in Keats's 1819 odes. These figures pass by the narrator three times. He compares them to images on a spinning urn. The narrator also uses the word "Phidian," which refers to the Elgin marbles. These famous sculptures were thought to be made by Phidias, a Greek artist.

As the poem goes on, the narrator talks about how these figures – Love, Ambition, and Poesy (poetry) – interrupt his laziness. He feels they have come to "steal away" his idle days. In the last stanzas, Poesy is described as a "daemon," which some think means it's a threat to the laziness the poet wants to keep. In the final lines, the poet tells the three images to leave: "Vanish, ye phantoms, from my idle spright, / Into the clouds, and never more return!" He wants to go back to enjoying the laziness that gives the poem its name.

Ode on Melancholy

"Ode on Melancholy" is the shortest of Keats's 1819 spring odes. It has three stanzas, each with 10 lines. It originally had four stanzas, but the first one was removed before the poem was published in 1820. The poem describes the narrator's thoughts on sadness, or melancholy. It speaks directly to the reader, unlike many of Keats's other odes.

This lyrical poem explains how melancholy can start. Then, it gives the reader different ways to deal with these sad feelings. The poem uses personification, which means it gives human qualities to ideas. Joy, Pleasure, Delight, and Beauty become characters. They interact with a man and his female partner mentioned in the poem. Keats himself doesn't appear as a character in the poem. There's no mention of him feeling melancholy.

In the last stanza, the poet says that the woman lives in Beauty. But he adds that this beauty "must die." Some experts believe this shows Keats's idea of "negative capability." This is a way of thinking where a person can be okay with not knowing everything or with things being uncertain. In this poem, only the beauty that will eventually die meets Keats's idea of true beauty.

Ode to a Nightingale

"Ode to a Nightingale" is the longest of the 1819 odes, with 8 stanzas, each having 10 lines. The poem starts by describing how the poet feels. He uses phrases like "numbless pains" and "not through envy of thy happy lot" to show his physical state. Even though the ode is written "to a Nightingale," the first lines focus more on the narrator than on the bird. Some experts say that as the nightingale's song becomes "pure self-expression," the reader is no longer part of the conversation.

In the third stanza, the poet asks the nightingale to "Fade far away." He is pushing it away, just like the narrator in "Ode on Indolence" rejects Love, Ambition, and Poesy. It's also like the poet in "Ode on a Grecian Urn" makes the figures on the urn silent. In the fourth stanza, the poet says he will fly to the nightingale, not the other way around. He will fly on the "wings of Poesy" (poetry). This makes some believe that while the poet wants to connect with the bird, the real connection is between the poet and what he imagines the nightingale's song to be.

At the end of the poem, the poet wonders if the bird's song was real or just a dream: "Was it a vision, or a waking dream? / Fled is that music:—do I wake or sleep?" The idea of imagination comes up again. The poet seems unable to tell the difference between his own artistic imagination and the song that he thinks inspired it.

Ode to Psyche

"Ode to Psyche" is a 67-line poem with stanzas of different lengths. Keats created its form by changing the structure of a sonnet. The ode is written to a character from Greek mythology, showing how much ancient Greek culture influenced Keats. The poet begins his talk with "O GODDESS!"

Psyche was a creature so beautiful that even Cupid, the god of love, fell in love with her. The narrator is also drawn to her. His artistic imagination makes him dream of her: "Surely I dream'd to-day, or did I see / The wingèd Psyche with awaken'd eyes." As he compares himself to Cupid, he mixes Cupid's feelings with his own. He imagines that he, too, has fallen in love with Psyche's beauty.

However, the poet understands that there's a big time difference between ancient Greek characters and himself. He says, "even in these days [...] I see, and sing, by my own eyes inspired." In line 50, the poet declares, "Yes, I will be thy priest, and build a fane" (a temple). Some experts suggest this means the poet himself becomes a "prophet of the soul." He admires Psyche's beauty and tries to imagine himself in Cupid's place. Some critics, like T.S. Eliot, believe this is the most important of Keats's six great odes.

To Autumn

"To Autumn" is a 33-line poem divided into three stanzas, each with 11 lines. It talks about how autumn is a time of growth and ripening, but also a time when things get ready for winter and death. Keats used the skills he learned from his earlier 1819 odes to write "To Autumn." However, he left out some parts of the previous poems, like having a specific narrator. Instead, he focused on the themes of autumn and life itself.

The poem talks about ideas without showing a clear passage of time in the scene. Keats called this "stationing." The three stanzas of the poem highlight this idea by changing the images. They move from summer to early winter, and from day turning into dusk.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |