José María Linares facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

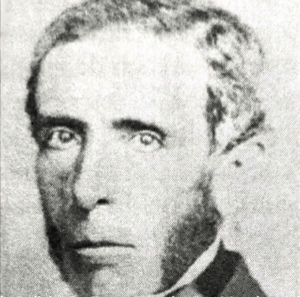

José María Linares

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 13th President of Bolivia | |

| In office 9 September 1857 – 14 January 1861 |

|

| Preceded by | Jorge Córdova |

| Succeeded by | José María de Achá |

| Minister of Interior and Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 16 November 1839 – 10 June 1841 |

|

| President | José Miguel de Velasco |

| Preceded by | Manuel María Urcullu |

| Succeeded by | Manuel María Urcullu |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

José María Linares Lizarazu

1808 Ticala, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (now Bolivia) |

| Died | 23 October 1861 (aged 53) Valparaíso, Chile |

| Spouse | Nieves Frías Gramajo |

| Parents | José Linares Josefa Lizarazu |

| Education | University of Saint Francis Xavier |

| Signature |  |

José María Linares Lizarazu (born July 10, 1808 – died October 23, 1861) was an important Bolivian lawyer and politician. He served as the 13th president of Bolivia from 1857 to 1861. He is known for trying to bring order and honesty to the government.

Contents

Early Life and Education

José María Linares was born in 1808 in Tical, Potosí, which is now part of Bolivia. His family owned a large farm called a hacienda. He came from a well-known and wealthy family.

He received his education at the Royal and Pontifical University of San Francisco Xavier in Sucre. This was a very respected university at the time.

His Path in Politics

From a young age, Linares was interested in politics. He held several government jobs in different administrations. In 1839, President General José Miguel de Velasco asked him to be the Minister of the Interior.

After this, Linares became Bolivia's Minister to Spain. There, he worked on an important agreement that officially recognized Bolivia's independence. He also served as the president of the Senate. In 1848, he briefly took charge of the government when President Velasco was away.

Linares soon became the leader of a group called the Partido Generador. This group believed in democracy and wanted civilians, not the military, to control politics. They wanted the army to stay in their barracks. This made many military-led governments of the time suspicious of him. He was even sent into exile a few times. However, he became the most important civilian leader who supported the country's laws. More and more people began to follow him.

During the time of President Manuel Isidoro Belzu, Linares often planned ways to remove the leader from power. These plans and many rebellions did not succeed at first. But they did make Belzu very tired. Because of the constant uprisings, Belzu eventually gave up his power. He handed control to his son-in-law, General Jorge Córdova. Belzu then left for Europe. Linares quickly began to plan against Córdova as well.

Becoming President of Bolivia

In 1857, Linares became president after a military takeover that supported civilian rule. This was new for Bolivia. He was one of the first civilian presidents the country had ever seen. After removing General Córdova, Linares made his rule official by winning an election by a large number of votes.

A Time of Change

When Linares first became president, his government was very active and honest. He introduced many new ideas and changes. He worked hard to stop corruption and bad practices in the government.

However, by doing this, he made many enemies. These enemies then started to plan against him. Rebellions and uprisings against his rule became common.

From President to Dictator

To stay in power, Linares made a surprising decision in 1858. He declared himself "Dictator for Life." This meant he would rule by his own orders and with military force. He said he was doing this to bring order and stop future takeovers.

This decision went against everything he had always believed in. As a result, he became very unpopular. In January 1861, his own Minister of War, José María de Achá, led a takeover that removed Linares from power.

Linares was sent away to Chile. There, he wrote a pamphlet for the Bolivian National Congress. This writing caused a stir in the country. It shared his thoughts on his time as president and his beliefs. José María Linares died just a few months after being removed from office. He passed away in Valparaíso, Chile, on October 23, 1861, as his health was already getting worse.

See also

In Spanish: José María Linares para niños

In Spanish: José María Linares para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |