Louis-Nicolas Robert facts for kids

Nicolas Louis Robert (born December 2, 1761 – died August 8, 1828) was a French soldier and mechanical engineer. He is famous for inventing a machine that made paper in a continuous roll. This invention later became the basis for the modern Fourdrinier machine, which is still used today for making paper.

In 1799, Robert received a special document called a patent for his amazing machine. This patent meant he was officially recognized as the inventor of the first machine to make "continuous paper." However, after some disagreements and money problems with the Didot family, Robert lost control of his invention. His machine was then taken to England and improved even further. Robert's invention became the main idea behind the Fourdrinier machine, which changed how paper was made forever. Later in his life, Robert became a school teacher and sadly, he passed away without much money.

Early Life and Military Career

Nicolas Louis Robert was born in Paris, France. His parents were older, and he was a somewhat weak child. But he was also very smart and eager to learn. He got a great education, focusing on science and math, from a religious group called the Minimes. He felt bad that he was a financial burden to his family.

When he was 15, he tried to join the army to help in the American Revolution, but he was too young. Four years later, he was finally accepted into the military. On April 23, 1780, he joined the Grenoble Artillery and was sent to Calais. In 1781, he moved to another artillery group and went to Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), where he fought against the English. He served in the army for about 14 years and became a sergeant major. Another story says he left the army in 1790, when he was 28.

On November 11, 1794, Robert married Charlotte Routier. Their wedding was a simple civil ceremony, meaning it was recognized by the government, not a church. This was common after the French Revolution, when marriage became a civil contract.

Inventing the Paper Machine

Around 1790, after leaving the army, Robert started working at a famous publishing company in Paris owned by the Didot family. He first worked as a clerk for Saint-Léger Didot. Later, he became an "inspector of personnel" at Pierre-François Didot's paper factory in Corbeil-Essonnes. This factory was very old and respected, making paper for important things like money for the government.

Both Robert and Didot were frustrated with the constant arguments among the workers who made paper by hand. Making paper by hand was a slow and difficult process. This made Robert want to find a mechanical way to make paper instead of relying on manual labor.

Dard Hunter, who wrote a book about papermaking, said that Robert created his machine because of "the constant strife and quarrelling among the workers of the handmade papermakers' guild." Robert wanted to replace the hand labor with a machine.

Didot thought Robert's first ideas were not very good, but he saw enough promise to keep going. He paid for a small test model. This model was finished by 1797, but it didn't work well. Robert felt discouraged, so Didot gave him a different job for a few months. After a break, Didot encouraged Robert to try again with the paper machine. He even gave Robert several mechanics to help him.

The next model was better. So, Didot told Robert to build a full-size machine. This new machine was a success! It made two sheets of "well felted" paper, meaning the paper fibers were well-connected.

Getting the Patent

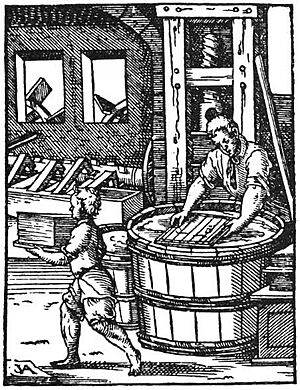

After Robert's successful machine was built in 1798, Saint-Léger Didot urged him to apply for a patent. Before this invention, paper was made one sheet at a time. Workers would dip a frame with a screen into a vat of pulp. They would then remove the frame, press out the water, and let the pulp dry. The frame couldn't be used again until the paper sheet was removed.

Robert's machine had a moving screen belt. This belt would receive a steady flow of paper pulp. It would then deliver a continuous, unbroken sheet of wet paper to a pair of rollers that squeezed out the water. As the long strip of wet paper came off the machine, workers would hang it by hand over cables or bars to dry.

With Didot's encouragement, Robert and Didot went to François de Neufchâteau, who was the Minister of the Interior in France. They applied for a patent. In 1799, the French government granted Robert the patent for his invention. He paid 8,000 francs for it.

On September 9, 1798, Robert wrote a letter asking for the patent. He explained that he had worked hard to simplify paper making. He wanted to make paper with much less effort and create very long sheets using only machines. He said his machine could make paper 12 to 15 meters long if desired. Robert also thanked Citizen Didot for his great help, providing his workshop, workers, and money. He asked the minister to grant him the patent for 15 years for free, as he couldn't afford the fee.

The Bureau of Arts and Trades, a government office, sent someone to see Robert's machine. They said that Robert was the first to invent a machine that could make paper from a vat. They noted that his machine made wide paper of endless length and that the paper was of perfect quality. They declared it a completely new invention that deserved support.

The Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, another important institution, paid Robert three thousand francs. This money was for him to build another model of his machine for a permanent display at the Musée des Arts et Métiers.

In 1785, Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf had invented a machine for printing dyes on wallpaper. Robert's invention was important because it not only made paper making faster, but it also allowed for continuous rolls of patterned and colored paper. This meant new designs and beautiful colors could be printed and used in homes across Europe.

The Machine Goes to England

Robert and Didot had disagreements about who owned the invention. Eventually, Robert sold both the patent and the first machine to Didot for 25,000 francs. However, Didot didn't make the payments to Robert. So, Robert had to go to court to get legal ownership of the patent back on June 23, 1801.

Didot wanted to improve and patent the machine in England, away from the problems of the French Revolution. So, he sent his English brother-in-law, John Gamble, to London.

In March 1801, John Gamble showed continuous rolls of paper from Robert's machine in London. He then agreed to share the London patent application with two brothers, Sealy and Henry Fourdrinier. They owned a major stationery business. Gamble received a British patent on October 20, 1801, for an improved version of Robert's machine. The Fourdrinier brothers then paid for the next steps of development. Gamble and Didot sent the machine to London. After six years and a lot of money (about £60,000) spent on improvements, the Fourdriniers received new patents. A Fourdrinier machine was set up at Frogmore, Hertfordshire, in England.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1812, Nicolas Louis Robert was not in good health. He had sold his invention and lost control of its development, which was now happening mostly in England. He decided to leave paper-making and moved to Vernouillet, France. There, he opened a small school. The French economy was struggling after Napoleon's defeats, and Robert was paid very little. He continued teaching until he passed away on August 8, 1828.

Today, there is a statue of him in front of the church in Vernouillet. A school in the area, the "Collège de Louis-Nicolas Robert," is also named in his honor.

In 1976, a man named Leonard Schlosser found Robert's original drawings at an auction. He made copies for other scholars and friends. No one knows where the original drawings are now.

Images for kids

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |