Marie-Louise (conscript) facts for kids

The Marie-Louises were young soldiers, mostly teenage boys, who joined Napoleon's army near the end of his rule. They were the last group of people forced to join the army (conscripts) in the First French Empire. The name comes from Empress Marie-Louise, Napoleon's wife. She signed orders in October 1813 to call up many new soldiers.

At this time, many French men had died or were hurt in the Napoleonic Wars. So, young boys were called to protect France from an invasion by a group of countries called the Sixth Coalition. Because there weren't enough soldiers, the army started taking boys as young as 14. They even accepted those who were quite short, around 5 feet 1 inch (1.55 m) tall.

Even though they had very little training, sometimes only two weeks, people at the time said these young soldiers were very brave. However, Napoleon's army was too small to stop the enemy. After Paris was captured, Napoleon gave up his power on April 13, 1814, which ended the war. The Marie-Louises were later shown in art and books, especially after the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. The name was even used again in 1914 for French soldiers in the First World War.

Contents

Why Were They Needed?

Forcing people to join the army, called conscription, had been a law in France since 1798. This law said that men between 20 and 25 years old had to serve in the military. They were supposed to serve for three years, but this time could be made longer during wartime.

This law wasn't always fair. Some areas had to send more men than others. By 1806, the age for joining the army was lowered to 19. The army also took volunteers as young as 18. Many people didn't like conscription, especially in the countryside. They worried they would never see their homes again. Some people even fought against it, and the government had to use force to make them join.

By 1813, Emperor Napoleon's army, called the Grande Armée, had lost many soldiers. This was because of huge losses in the failed invasion of Russia in 1812. There were also ongoing wars in Spain and Germany, and many soldiers got sick. Napoleon believed he needed 110,000 more soldiers to defend France from the coming invasion by the Sixth Coalition. So, he decided to call up even more people to join the army.

Calling Up New Soldiers

Napoleon called up many new soldiers through a series of laws and orders. These laws included groups of people who had not been forced to join before.

For example, in January 1813, orders were given to call up 100,000 men who had turned 20 in the past few years. Another 150,000 men who would turn 20 in 1814 were also called. Later in the year, more orders were issued. One important order on October 9, 1813, called for 120,000 men. This order was signed by Empress Marie-Louise, which is how the young soldiers got their name.

To find enough people, the army also lowered the minimum height for soldiers. It went from 5 feet 3 inches (1.60 m) before the wars, to 5 feet 2 inches (1.57 m) in 1810, and then to 5 feet 1 inch (1.55 m) in 1813. By 1814, they even accepted men shorter than 5 feet (1.5 m) if they had no other health problems.

Many French soldiers were also stuck in enemy strongholds after a big loss at the Battle of Leipzig. By the end of 1813, Napoleon's main army had only about 70,000 men left.

At first, calling up new soldiers worked well in France. But by August, people started to resist. In areas that France had taken over, like Holland and Italy, it was hard to find enough new soldiers, and this caused trouble. The October orders signed by Marie-Louise were very strict. They said that these new soldiers were needed for "the salvation of France." Some boys as young as 18 were called up. Only those who were truly unable to serve or were the only person earning money for their family could be excused. The process was also made very fast. New soldiers had to report to a training camp within two days of being chosen.

The number of soldiers needed from each area was based on how many they had failed to provide before. Some areas were excused, like those under enemy threat or far-off Corsica. Some areas had their calls postponed because of past problems or ongoing unrest. Despite these issues, the October call-up was fairly successful in some parts of France, especially around Paris. However, a very large call-up in November completely failed. By January 1814, getting new soldiers to the army was very slow because of "confusion and disorder" in France.

Life as a Soldier

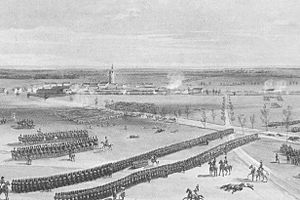

About 25,000 men actually joined the army from the Marie-Louise orders. Most of them, over 20,000, joined the Imperial Guard, especially the Young Guard. They were slowly added to existing guard groups. They also formed new regiments like the 14e Regiment de Tirailleurs and 14e Régiment de Voltigeurs of the Imperial Guard.

These new soldiers received very quick and short training. Napoleon said they should all learn to shoot a musket, even if it was a very quick lesson. It was common for them to get only two weeks of training. Few received as much as a month. This was much less than earlier soldiers, who usually got 90 days of training. The Marie-Louises were not well-trained in shooting, marching, or fighting in small groups. However, some had learned to shoot before as poachers (illegal hunters).

Napoleon knew these poorly trained troops had limits. He asked that groups made only of new soldiers be half the usual size. This way, officers could watch over them better. He used these groups to hold steady positions in his battle lines. However, the Young Guard, made up of many Marie-Louises, were used as shock troops. They attacked in large, close formations.

Marshal Auguste de Marmont, a high-ranking officer, remembered this time. He said the troops were very brave. "New soldiers, who arrived the day before, joined the fight and acted bravely, like old soldiers." He told a young soldier who wasn't shooting, "Why don't you shoot?" The soldier simply replied, "I would shoot as well as any other soldier if I had someone to load my gun." This shows how little training some of them had.

The new soldier units suffered many losses in the 1814 campaign. Napoleon himself said, "the Young Guard melts." By this time, Napoleon's armies were too weak to fight off the Sixth Coalition's invasion. Paris fell on March 30–31, and Napoleon gave up his power on April 13. This ended the war.

The Term "Marie-Louise"

The term "Marie-Louise" (singular) or "Marie-Louises" (plural) doesn't have one exact meaning. Historians have different ideas about who it refers to. Some say it's only for those called up in 1815 by the orders signed by Empress Marie-Louise in October 1813. Others use it for all soldiers called up in 1814 and 1815. A third group uses it for anyone called up between 1813 and 1815. Today, it generally means all the young soldiers who served in the last years of Napoleon's empire.

The name likely came from the older, experienced soldiers, called grognards (grumblers), in the Old Guard. It was a kind of dark humor common in France as the war ended. Even though military writers used the term, historians didn't pick it up for many years.

The use of the term "Marie-Louise" became less popular over time as political views changed in France. Few school books before the First World War used it. However, it became popular again in 1914-15. At that time, men were again called up for war, and the name was used for these new soldiers too.

Marie-Louises in Art and Books

The term "Marie-Louise" wasn't used right away in art and books. Even when artists showed new soldiers from Napoleon's time, they didn't use the term. In fact, these young soldiers weren't a popular subject for art back then. Maybe it was because their simple uniform of a hat, cape, and musket wasn't very exciting to paint.

One of the few early paintings that might show them is Ernest Meissonier's 1864 Campagne de France, 1814. It shows a line of soldiers in the background who could be new recruits. Adolphe Lalauze's painting Le retour des dragons de l'armée d'Espagne (The return of the dragoons from the Army of Spain) shows a group of Marie-Louises welcoming cavalry soldiers.

After the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, more art about the Marie-Louises appeared. Artists were inspired by the spirit of 1814. The first artwork named after them was Pierre Victor Robiquet's Les Maries-Louises à Champaubert. It shows a group of new soldiers fighting Russian Cossacks at the Battle of Champaubert on February 10, 1814.

The 1864 novel Histoire d’un conscrit de 1813 and its follow-up Waterloo by Erckmann-Chatrian are linked to the Marie-Louises. These novels are against war and focus on a young watchmaker who is forced to join Napoleon's army. Most other French books from the 1800s focused on soldiers who volunteered.

There was a new interest in the Marie-Louises during the First World War. This was because France was again calling up many new soldiers when threatened by invasion. A monument at the site of the Battle of Craonne, which honored the original Marie-Louises, was destroyed in fighting early in the war. A new monument was built in 1927. It honored both the soldiers of 1814 and those of 1914. It features statues of a soldier from 1814 and a poilu (French soldier) from 1914, holding a French flag together.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |