Mendocino War facts for kids

The Mendocino War was a difficult time for the Yuki people and white settlers in Mendocino County, California. It happened between July 1859 and January 18, 1860. This conflict started because settlers moved onto Native American lands and took people. The Yuki people then fought back. Sadly, hundreds of Yuki people died during this time.

In 1859, a group of local rangers called the Eel River Rangers, led by Walter S. Jarboe, began raiding the area. Their goal was to force Native Americans off settler lands. They wanted to move them to the Nome Cult Farm, which was near the Mendocino Indian Reservation. By 1860, when the rangers stopped, Jarboe and his men had killed 283 warriors. They also captured 292 people and killed many women and children. The rangers themselves only lost 5 men in 23 fights. The state paid the rangers over $11,000 for their services. Experts today believe the harm to the area and Native Americans was much worse than reported. Many other groups also raided Native American lands.

Other settlers also formed their own raiding groups. They joined Jarboe to remove Native Americans from Round Valley. Those who survived were sent to the Nome Cult Farm. There, they faced many hardships, which was common on reservations back then. After the conflict, some people called it a "slaughter" instead of a "war." Later historians have even called it a "genocide."

Contents

What Caused the Conflict?

Round Valley is in northeastern Mendocino County in Northern California. It was home to many Native American tribes. The Yuki were the largest group. Their land covered about 1,100 square miles. The Yuki were not one single political group. Instead, they were many independent communities. They shared a language and culture, and each community had its own leaders.

In 1853, California started its Indian Reservation System. Thomas J. Henley was in charge of it. By 1854, white settlers found Round Valley. Pierce Asbill, the first white man to see the area, thought there were about 20,000 Native Americans living there. Experts now think this number was a bit high. But by 1856, there were 12,000 Native Americans in Round Valley.

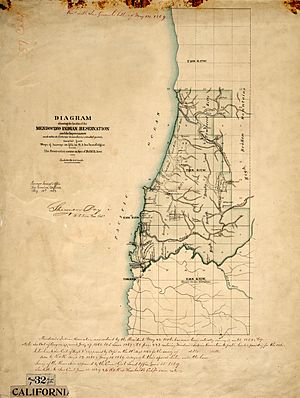

A few families moved into Native American territory. But many settlers were hunters, people hiding from the law, or drifters. They lived off the land and came for its natural resources. In the same year, Thomas Henley sent Simmon Pena Storms to start the Nome Cult Farm. It was first meant as a resting place for Native Americans and travelers. But the Nome Cult Farm grew into its own reservation. It took up 5,000 acres of northern Round Valley. This left over 15,000 acres for white settlers.

Growing Problems for Native Americans

Even with land set aside for white settlers, the government struggled to stop newcomers. Settlers moved onto the Nome Cult Farm and Mendocino Reservation. As settlers took over Native American land, it became hard for the Native Americans to survive. Those on the Nome Cult Farm lived very difficult lives. They grew crops but received little benefit from their hard work.

Native Americans were not protected. They faced harsh treatment, including attacks, killings, and theft of their belongings. They also suffered from disease and hunger. Many white settlers took Native American women and children. They forced them into labor. Native Americans at Nome Cult Farm were overworked. They could even be killed if their work was not good enough.

White settlers continued to use Native American land. Many families fenced off thousands of acres. They removed fences from the Nome Cult Farm. They let their animals graze on Native American land, even where crops were growing. The California Reservation System was often corrupt. It had problems with fraud and misuse of money. This meant there was little help for Native Americans. As more settlers took Native American land and resources, food sources for Native Americans became scarce.

When Tensions Increased

Since ranching methods were not very advanced back then, settlers had trouble keeping their animals on their land. Barbed wire had not been invented yet. Many tried to train their animals to stay in one area, but this did not always work. Animals often wandered off. The new, unfamiliar land with cliffs and predators made it worse. Many cattle and horses died naturally.

However, settlers blamed Native Americans for any missing animals. They believed Native Americans were stealing them. They held public meetings to create anger towards Native Americans. In response, settlers continued to attack Native American land and resources. With no police force, the reservation could not stop theft or abductions of Native Americans. Some locals, like Dryden Lacock, even said settlers, including himself, were going on small raids. They killed "50-60 Indians a trip."

Finally, facing starvation and few choices, Native Americans began to fight back. In 1857, a Yuki person shot William Mantle while he was crossing the Eel River. In 1858, John McDaniel, a white man, was killed. Both men were known for harming Native Americans. Reports from the U.S. Army said Native Americans were provoked in both cases.

Government Gets Involved

As tensions grew, settlers asked the U.S. Army for help. In 1859, the 6th U.S. infantry, led by Major Edward Johnson, came to Round Valley. Major Johnson sent Lieutenant Edward Dillon with 17 men to check the area. Lieutenant Dillon reported that the settlers had not told the full story. He found that settlers had already killed hundreds of Native Americans. The Native Americans' actions were often in revenge or to survive.

Lieutenant Dillon reported that the problem went all the way up to Superintendent Henley. Henley had helped organize many of these raids. In fact, Henley worked with Judge Serranus C. Hastings. Hastings was a former Iowa Supreme Court Justice. They planned to remove Native Americans from the area. As part of their plan, they launched raids. They also held town meetings where settlers shared their complaints. This led to more prejudice and hatred towards Native Americans.

Judge Hastings was also involved in real estate and livestock. In one case, Native Americans took Judge Hastings's valuable horse. This was in response to beatings they received from his ranch manager, H.L. Hall. Hall had been involved in many brutal attacks on Native Americans. He complained to Lieutenant Dillon that Native Americans were stealing supplies. Dillon told Hall to let him handle it, but Hall ignored him. Hall took his own men on a raid. By March 23, 1859, Hall and his men had killed about 240 Native Americans. Dillon reported that Hall did not care if Native Americans were guilty or innocent. He said Hall's killings of women and children were unprovoked. Later, when Hall asked for soldiers to protect his animals, the soldiers refused. They were only ordered to defend against a Native American attack, and they did not believe this was one. Native Americans faced a terrible choice: starve on reservations that gave them no food, or go into the mountains and risk being killed by settlers.

Walter S. Jarboe and the Mendocino War

As the conflict became very intense, Judge Hastings decided to fire Hall. He moved all remaining Native Americans to the Mendocino Reservation. He did this more to protect his property than to help the Native Americans. In June 1859, a group of 39 settlers from Round Valley, called the "Citizens of Nome Cult Valley," asked the governor of California, John B. Weller, for help. They wanted protection from Native American attacks.

This request was supported by Henley and Judge Hastings. It was one of many letters and requests settlers sent to the governor. They asked for government money for volunteers to protect white property. In these requests, settlers said they planned to remove Native Americans from Mendocino through a "war of extermination." Governor Weller asked the Army for advice. He wanted to know if the settlers' claims were true. The settlers said over $40,000 in property damage had happened. They also claimed over 70 white people had been killed by Native Americans. The requests also asked that Walter S. Jarboe, a Mendocino County resident, be made captain of this group. In 1858, Jarboe had led a raid on the Mendocino Reservation that killed over 60 Native Americans. Major Johnson and Lieutenant Dillon sent reports that told a different story. They said only 2 white people and about 600 Native Americans had been killed in the past year.

Meanwhile, Hastings got tired of waiting. He created a new company anyway, without federal money, with Jarboe as captain. This company was often called the Eel River Rangers. Hastings and Henley promised to pay for them. (They later broke this promise, making the state pay for Jarboe and his men). From July 1859 to January 1860, Jarboe and his men attacked Native American lands. They killed many Native Americans.

Jarboe and his men claimed Native Americans were guilty of theft and violence. They engaged in what was called an "ethnic cleansing genocide." To try to justify their actions, Jarboe and his men used dead animals from raided villages. They tried to make it look like Native Americans were stealing. It was a "shoot-first, ask-questions-later" approach. This gave Jarboe and his men the power to act as "judge, jury, and executioner." From July through mid-August, Jarboe and his men had already killed 50 men, women, and children. This caused Major Johnson to write to Governor Weller. The governor wrote to Jarboe several times. He approved the raids but asked Jarboe to spare women, children, and innocent Native Americans. Jarboe mostly ignored these letters. Through October, Jarboe and his men continued to rampage. They killed and captured Native Americans. Those they captured were sent to the Mendocino Reservation and the Nome Cult Farm.

Native Americans faced huge challenges. They suffered from hunger, had weaker weapons, and faced constant surprise attacks. Their position on reservations made them vulnerable. They also had no way to speak up for themselves. Jarboe's forces also angered some white settlers. They killed their animals if they refused to give them food or supplies. However, most of the harm was done to Native Americans. The timing was especially deadly. Winter was coming, and Native Americans had spent months preparing and harvesting crops. Now, with the raids, the men who farmed and hunted and the women who gathered and made food were killed. Native American winter supplies were stolen and lost.

Jarboe and his men continued their raids and killings through the winter. Their goal was to remove Native Americans completely from Round Valley. Some settlers also helped. Ranchers led their own attacks and raiding parties. In one 22-day period, 40 ranchers killed at least 150 Native Americans. Finally, on January 3, 1860, Governor Weller disbanded Jarboe's group. The public quickly opposed this decision. They asked Governor Weller to bring back the Eel River Rangers, but their protest was not successful.

|

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |