Social norm facts for kids

Social norms are like unwritten rules that guide how people behave in a group or society. They are shared ideas about what is acceptable and what is not. These norms can be informal understandings, like knowing to say "please" and "thank you," or they can be formal rules, like laws. Social norms are very powerful in shaping how we act and interact with others every day.

Norms are different from personal ideas or feelings because they are shared by a group and are about how people act. They depend on the situation, the group you are with, and even the time in history.

Experts often talk about different kinds of norms:

- Regulative norms tell us what we can or cannot do.

- Constitutive norms help shape our understanding of things, like what it means to be a student.

- Prescriptive norms tell us what we should do.

People follow norms for different reasons. Sometimes, they follow them because it feels like the right or proper thing to do in a social situation. Other times, they follow norms because they have thought about the good or bad results of their actions.

Norms often go through three stages: 1. Norm emergence: This is when new ideas about behavior start to appear, often pushed by people who strongly believe in them. 2. Norm cascade: This is when a norm becomes widely accepted by many people. 3. Norm internalization: This is when a norm becomes so common that people follow it almost without thinking.

Some norms are very strong and rarely broken, while others are broken more often. We can see norms in how groups behave and in what they talk about as being right or wrong.

Contents

What Are Social Norms?

There are many ways to define social norms, but most experts agree on a few key points:

- They are social and shared among people in a group.

- They are about behaviors and help us make decisions.

- They tell us what we should or should not do.

- They show the socially acceptable ways a group of people live in a society.

One simple way to think about norms is that they are "collective expectations about proper behavior for a certain identity." For example, a student is expected to do homework.

Some experts say norms are "cultural things that tell us what to do and not to do in specific situations." Others see them as "group-level ideas about behavior," meaning they are widely shared expectations of what will get you approval or disapproval from others.

A famous economist, Peyton Young, describes norms as "patterns of behavior that keep themselves going within a group." He says that everyone expects others to follow the norm, and everyone wants to follow it if they expect others to do the same.

Words like "customs," "rules," and "laws" are often used to mean similar things to norms. Laws are just very formal versions of norms. Sometimes, laws and norms might even disagree! For example, a law might forbid something, but a norm in a small group might still allow it. Norms are not just a collection of individual opinions; they are shared beliefs about behavior.

How Norms Start and Spread

Groups can adopt norms in different ways.

Some norms appear naturally without anyone planning them. For example, people might start lining up for a bus without being told to. These informal norms develop slowly as people repeatedly use certain actions to guide behavior. They are not written down but are generally accepted routines people follow daily.

Norms can also be created on purpose by people called "norm entrepreneurs." These are individuals who try to convince others to adopt new ideas about what is right or proper. Formal norms, like laws, are usually created this way. Many norms we follow, like driving on a certain side of the road or not speeding, are examples of norms that came from a design.

Experts Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink describe three steps in a norm's life:

- Norm emergence: People who believe in a new idea try to convince others to accept it as good and proper.

- Norm cascade: The norm becomes widely accepted, reaching a point where many people adopt it, and leaders encourage others to follow.

- Norm internalization: The norm becomes so common that people follow it almost automatically, without thinking.

Several things can make a norm more influential:

- Legitimation: People who are unsure about their own place in a group might be more likely to accept norms.

- Prominence: Norms held by people who are seen as successful or desirable are more likely to spread.

- Intrinsic qualities: Norms that are clear, long-lasting, and apply to everyone are more likely to become important.

- Path dependency: Norms that are connected to existing norms are more easily accepted.

- World time-context: Big events like wars or economic problems can make people look for new norms.

Some experts believe norms are created because an individual's actions affect others in the group. Others think norms are created because people want positive social reactions. This means norms don't always help the whole group; sometimes, they might even be harmful.

Norms can also change. People with power can often convince others to change existing norms, especially if they refer to older, more basic rules or past examples. Being close to other people in a social group also helps keep norms strong.

How Norms Move Between Groups

People might bring norms from an old group to a new one, and these norms can be adopted over time. When people don't know how to act, they often use their past experiences to guide them. What worked before might work again. In a new group, different people might bring different ideas about proper behavior. Over time, the group will decide together what the right action is, often by combining ideas from several members. This way of forming norms can happen quickly and subtly.

Groups accept norms by seeing them as reasonable and proper ways to behave. Once a norm is set, it becomes part of how the group works and is harder to change. While new people can sometimes change a group's norms, it's much more likely that the new person will adopt the group's norms and ways of thinking.

Breaking Social Norms

Deviance means not following the norms that most people in a community or society accept. If group members don't follow a norm, they might be seen as "deviant." In some cases, this can lead to them being treated as outcasts. However, for children, some deviant behavior is expected. But this tolerance quickly disappears if the deviance becomes a criminal act. Crime is considered one of the most extreme forms of deviance.

What is considered "normal" depends on the culture and place where people are interacting. In psychology, someone who often disobeys group norms might become an "institutionalized deviant." Like in sociology, these people might be judged by others for not following norms. At first, group members might try to pressure a non-conformist, talking to them or explaining why they should follow the rules. But if someone keeps disobeying, the group might eventually give up on them. The group might not kick them out, but they might only give them superficial attention.

For example, if a worker is always late for meetings, breaking the office norm of being on time, a boss or co-worker might wait for them and then ask what happened. But if it keeps happening, the group might start meetings without them because "they are always late." The group then ignores the person's disobedience, which reduces their influence in future group discussions.

How much a group tolerates someone breaking norms can vary. Not everyone gets the same treatment. Individuals can build up "good behavior" by following norms, like saving up credits. These "idiosyncrasy credits" are like a theoretical currency that helps us understand why some people get more leeway. For example, a teacher might more easily forgive a straight-A student for misbehaving than a student who is always disruptive.

Some people start with more credits. For instance, child movie stars who go to college might have more freedom in adapting to school norms than other new students. Also, leaders or people in high-status positions might start with more credits and sometimes seem "above the rules." But even their credits are not endless; if their disobedience becomes too extreme, leaders can still face rejection from the group.

Breaking a norm can also cause strong emotions, like guilt. Guilt is often linked to a sense of duty and moral obligation. It's that negative feeling you get after doing something you question. It can feel bad and even like a form of self-punishment. It's like staining yourself and needing to clean away the "filth." Guilt can push you to do more "honorable" actions in the future.

A study in 2023 found that societies without much industry punished norm violations differently. The punishments depended on the type of norm broken and the society's economic system. For example, societies that stored food might use material punishments, while those that relied more on hunting might use physical punishments.

How Norms Affect Behavior

While general ideas don't always lead to specific actions, norms are all about behavior. They are shared ideas about how people should act.

Norms that go against the wider society's behaviors can still exist and be kept alive within smaller groups. For example, some groups like cheerleading squads or sports teams have higher rates of certain behaviors than society as a whole. Social norms help keep order and organize groups.

In psychology, norms are seen as "mental pictures of appropriate behavior" that guide us in different situations. Studies have shown that messages about norms can encourage good behavior, like reducing alcohol use, increasing voting, and saving energy. Psychologists say that norms have two parts: how much a behavior is actually done, and how much the group approves of that behavior.

Social Control Through Norms

Even though norms are not formal laws, they play a big role in controlling society. They are statements that guide conduct. Norms tell us what is acceptable behavior in specific situations. They vary by culture, background, and location. They are the basis for ideas like "don't hurt others" or "keep your promises." Without norms, there would be no common understanding or limits. Even though laws are not meant to control social norms directly, society and law are connected, and one often influences the other.

Social norms can be enforced formally (like through punishments) or informally (like through body language or non-verbal cues). Because people often get physical or emotional support from being part of a group, groups can control "discretionary stimuli." This means groups can give or take away resources based on how well members follow norms, effectively controlling behavior through rewards and consequences. Research shows that the more an individual values group resources or sees group membership as important to their identity, the more likely they are to follow norms. Norms also show what behaviors a group thinks are important for its existence, because they represent shared beliefs. Groups usually don't punish members for actions they don't care much about. Norms in every culture create conformity, which helps people learn how to fit into their society.

As social beings, we learn when and where it's okay to say certain things, use certain words, discuss certain topics, or wear certain clothes. This knowledge about cultural norms is important for making good first impressions. We also learn through experience what kinds of people we can and cannot discuss certain topics with or wear certain clothes around. This knowledge comes from social interaction. For example, wearing a suit to a job interview to make a good first impression is a common social norm in many workplaces.

Robert Ellickson studied how people in neighborhoods and communities interact to show how social norms create order in small groups. He argued that in a small community, many rules and disagreements can be settled without a central government, just by how people interact.

Norms in Sociology

In sociology, norms are seen as rules that connect a person's actions to a specific reward or punishment. By guiding behavior, social norms create unique patterns that help us tell different social systems apart. This creates a boundary that shows who belongs in a specific social setting and who does not.

For some sociologists, norms guide how people interact in all social situations. Others believe that norms help create different roles in society, allowing people from different social classes to function properly. This power dynamic helps create social order. Some theories suggest that norms start as goal-oriented actions by individuals. If the benefits of an action outweigh the costs, a social norm might appear. The norm's strength is then judged by how well it can enforce its rules against those who don't contribute to the "best social order."

Another idea is that social norms help make future actions predictable. This speeds up social interaction because people can count on certain actions happening without having to wait for them. Important factors in making behavior standard are punishments and social roles.

How We Learn Norms

The idea of how likely behaviors are to happen again is discussed in the theories of B. F. Skinner. He said that operant conditioning plays a role in how social norms develop. Operant conditioning is how behaviors change based on their results. A behavior is more or less likely to happen again depending on what happens after it.

If someone breaks a social norm, they might face negative results. This could be a formal scolding, being ignored by others, or more serious punishments like fines. If the person stops the bad behavior after getting a negative result, they have learned through punishment. If they start doing a behavior that fits a social norm after something unpleasant is removed, they have learned through negative reinforcement. Reinforcement makes a behavior happen more, while punishment makes it happen less.

For example, imagine a child who paints on the walls for the first time. The parents' reaction will affect whether the child does it again. If the parent is positive, the behavior will likely happen again (reinforcement). But if the parent gives a negative consequence (like a time-out or showing anger), the child is less likely to repeat the behavior (punishment).

Skinner also believed that humans are taught from a very young age how to behave and interact with others, based on the influences of their society and location. We are built to fit in, and breaking norms is generally frowned upon.

Different Kinds of Norms

There isn't one perfect way to define all norms, but here are some common types:

Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink identify three types:

- Regulative norms: These norms "order and limit behavior." They tell us what we can and cannot do.

- Constitutive norms: These norms "create new actors, interests, or types of actions." They help define things.

- Evaluative and prescriptive norms: These norms have a "should" quality to them. They tell us what is right.

Experts also look at how strong or effective norms are based on factors like:

- The specificity of the norm: Clear and specific norms are usually more effective.

- The longevity of the norm: Older norms are often more effective.

- The universality of the norm: Norms that apply generally (not just to specific cases) are more effective.

- The prominence of the norm: Norms widely accepted by powerful people are more effective.

Some experts say that the strength of a norm depends on how much support there is for those who punish people who break the norm. This includes "metanorms," which are norms about how to enforce other norms. Also, if many different people support a norm, it tends to be stronger. Norms that are part of larger groups of related norms might also be more robust.

There are two main reasons why norms are effective:

- Rationalism: People follow norms because they are forced to, or because they calculate the costs and benefits, or because of rewards.

- Constructivism: People follow norms because they learn them socially and become used to them.

Peyton Young suggests that things that help support normal behavior include:

- Coordination: People acting together.

- Social pressure: The influence of others.

- Signaling: Showing others what you intend to do.

- Focal points: Clear, obvious solutions in a situation.

What Is Done vs. What Should Be Done

Descriptive norms show what people commonly do in certain situations. They describe what most people do without judging it. For example, if there's no trash on the ground in a parking lot, it suggests that most people there don't litter.

Injunctive norms, on the other hand, show what a group approves of for a certain behavior. They tell you how you should behave. If you see someone picking up trash and throwing it away, you might learn the injunctive norm that you ought not to litter.

Prescriptive and Proscriptive Norms

Prescriptive norms are unwritten rules that society understands and follows, telling us what we should do. For example, writing a thank-you note when someone gives you a gift is a prescriptive norm in American culture.

Proscriptive norms are the opposite; they are society's unwritten rules about what you should not do. These norms can be different in different cultures. For example, kissing someone you just met on the cheek might be okay in some European countries, but it's not acceptable in the United States, making it a proscriptive norm there.

Subjective Norms

Subjective norms are based on what you believe important people in your life want you to do. When combined with your own attitude toward a behavior, subjective norms influence your intentions. They represent the pressure you feel from important others to do, or not do, a certain behavior.

Thinking About Norms with Math

Over the past few decades, some experts have tried to explain social norms using mathematical ideas. By drawing graphs or trying to map the logic behind following norms, they hoped to predict whether people would conform. Models like the "return potential model" and "game theory" offer a more economic way of thinking about norms, suggesting that people might calculate the costs or benefits of different actions. In these ideas, choosing to obey or break norms becomes a more thought-out, measurable decision.

Return Potential Model

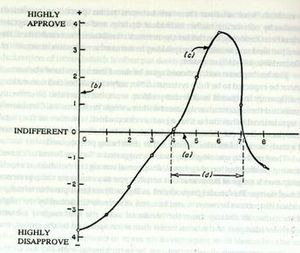

The return potential model, created in the 1960s, helps visualize group norms. On a graph, the amount of behavior is on the X-axis (labeled a in Figure 1), and the amount of group acceptance or approval is on the Y-axis (b in Figure 1). The graph shows the possible positive outcome for a person for a given behavior. You could plot a point for each amount of behavior to see how much the group likes or dislikes that action.

For example, imagine a norm among first-year graduate students about how many cups of coffee they drink daily. If the curve in Figure 1 shows this norm, we can see that if someone drinks 0 cups, the group strongly disapproves. The group disapproves of drinking fewer than four cups or more than seven cups.

- Point of maximum return: This is the point on the graph where the group likes the behavior the most. In Figure 1, the point just above 'c' at X=6 is the point of maximum return. For our coffee example, drinking exactly 6 cups of coffee would get the most social approval.

- Range of tolerable behavior: This is the amount of action the group finds acceptable. It includes all the positive area under the curve. In Figure 1, the range of tolerable behavior is 3 (from 4 to 7 cups). This means first-years only approve of drinking between 4 and 7 cups of coffee. Norms can have a narrow or wide range of acceptable behavior. A narrower range usually means the behavior has bigger consequences for the group.

- Intensity: This shows how much the group cares about the norm, or how much emotion is involved. It's represented by the total area under the curve, whether positive or negative. A norm with low intensity wouldn't have much approval or disapproval. A high-intensity norm would have very strong approval or disapproval ratings. In Figure 1, the norm seems to have high intensity, as few behaviors are met with indifference.

- Crystallization: This refers to how much agreement there is among group members about the approval for a certain amount of behavior. Some members might think the norm is more important than others. For example, a norm about coffee might have low crystallization because people have different ideas about caffeine. But a norm about not cheating on schoolwork would likely have high crystallization because everyone agrees it's wrong. The model in Figure 1 shows the overall group norm but not the crystallization.

Game Theory

Another way to understand social norms is through game theory. This field looks at how rational people make decisions when their actions affect others. A norm gives a person a general idea of how they should act. However, a rational person will only follow the rule if it benefits them.

The situation can be described like this: A norm creates an expectation of how other people will act in a given situation. A person then acts in the best way, given that expectation. For a norm to be stable, people's actions must keep that expectation going without change. A set of such stable expectations is called a Nash equilibrium. In a Nash equilibrium, no one person has a reason to act differently on their own. Social norms will be followed if the actions related to that norm are supported by the Nash equilibrium in most game theory situations.

From a game theory point of view, there are two reasons for the many different norms around the world. One is that the "games" (situations) are different. Different places might have different environments or people with different values, leading to different "games." The other reason is how people choose among possible stable outcomes, which is related to coordination. For example, driving is common everywhere, but in some countries, people drive on the right, and in others, they drive on the left. Both are stable norms, but they are different.

See also

In Spanish: Normas sociales para niños

- Anomie

- Breaching experiment

- Convention (norm)

- Enculturation

- Etiquette

- Heteronormativity

- Ideal (ethics)

- Ideology

- Morality

- Mores

- Norm (philosophy)

- Norm of reciprocity

- Normality (behavior)

- Normalization (sociology)

- Other (philosophy)

- Philosophical value

- Peer pressure

- Rule complex

- Social norms marketing

- Social structure

- Taboo

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |