Oahu sugar strike of 1920 facts for kids

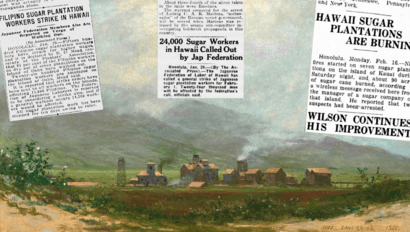

The Oahu sugar strike of 1920 was a big protest in Hawaii. It involved two main groups of workers: the Filipino Labor Union and the Federation of Japanese Labor. About 8,300 sugar plantation workers went on strike. They stopped working from January to July in 1920.

The workers wanted higher pay. They asked the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association for more money. In the end, their demands for better pay were met. During the strike, about 150 workers and their families got sick and died. They were living in very crowded places after being forced out of their homes. This made them more likely to catch the Spanish flu.

Contents

Why the Strike Happened

Before 1920, workers from different backgrounds often didn't work together. If one group went on strike, others would keep working. This made it hard for strikes to succeed.

Sugar plantation workers were paid very little. Their wages were barely enough to live on. When World War I started, prices for food and other things went up a lot. But workers' pay stayed the same. This meant many families struggled to buy what they needed. This problem continued even after the war ended.

Over time, the Filipino Labor Union and the Federation of Japanese Labor worked together. They united Filipino and Japanese workers. On December 4, 1919, the unions told the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association what they wanted. They asked for higher daily pay for men and women. They also wanted paid time off for women who had babies. The plantation owners first said no. They thought the workers would not be able to keep striking for long.

The Strike Begins

The strike officially began for Filipino workers on January 20, 1920. Japanese workers joined on February 1, though many had already stopped working. About 8,300 workers took part in the strike. This included 5,000 Japanese workers, 3,000 Filipino workers, and 300 workers from other groups. These other groups included Portuguese, Chinese, Puerto Ricans, Spanish, Mexicans, and Koreans. The strike spread across six different sugar plantations.

The plantation owners tried to stop the strike. They forced striking workers and their families out of their homes. These homes were usually on plantation land. In total, 12,020 people were forced to leave. These families found shelter in many places. Some stayed with friends or family who supported the strike. Others lived in hotels, tents, or empty buildings. Buddhist and Shinto churches also offered help. However, Christian churches often refused to help the homeless strikers.

One big problem for the strikers was getting enough food. The Japanese union had saved a lot of money, about $900,000. This money was for their members and families during the strike. The Filipino union relied on donations from Filipinos working on other plantations. But soon, the Filipino union ran out of money. They were close to starving. If they went back to work, the whole strike would fail. So, the Japanese union used its savings to help the Filipino workers. This saved the strike from ending early.

After many months, boredom became a problem for the strikers. To keep spirits up, the Federation of Japanese Labor organized a protest march. On April 3, 3,000 people marched down King Street.

Sickness During the Strike

During the strike, the Spanish flu spread across Hawaii. Many people got sick. Among the Japanese strikers, 1,056 got the flu, and 55 died. Among Filipino strikers, 1,440 got sick, and 95 died. The strikers blamed the plantation owners for these deaths. They believed that being forced out of their homes and living in crowded places made them more vulnerable to the flu.

Strike Ends and Results

The strike lasted for more than six months, finally ending on July 1. The workers and plantation owners reached an agreement. This agreement was made at the Alexander Young Building. The workers received a 50% pay raise and more benefits.

Some workers felt the strike was not a success at first. This was because the full benefits of the agreement took about six months to appear. The strike was hard on both sides. About 1,000 strikers eventually went back to work before the end. Also, more than 2,000 new workers were hired to replace strikers. The plantation owners lost about $12,000,000 in money they could have earned.

Even though the strike was difficult, it was successful in getting better pay and conditions for workers. It also showed the plantation owners that Filipino and Japanese workers could unite and fight for their rights.