Origin of language facts for kids

The origin of language is a fascinating mystery. It explores how humans first started talking and communicating with words. Scientists have studied this for a long time. They look at things like old bones (fossils), tools from ancient times, and how different languages are used today. They also compare human language to how animals communicate. Many think that language started around the same time humans began to act and think in modern ways. But there is still much to learn!

For a long time, studying how language began was seen as too hard. In 1866, a group called the Linguistic Society of Paris even banned discussions about it! But since the 1990s, many experts like linguists, archaeologists, and psychologists have started looking into it again with new ideas.

Contents

How Do We Study Language Origins?

Scientists have different ways to think about how language started:

- Continuity theories: These ideas suggest that language is very complex. It probably didn't just appear all at once. Instead, it slowly grew and changed from simpler ways our early human ancestors communicated.

- Discontinuity theories: These ideas say that language is special and very different from how animals communicate. They believe language appeared quite suddenly during human evolution.

- Innate vs. Learned: Some theories think language is mostly something we are born with, like a built-in ability. Other theories believe language is mostly learned from interacting with others.

Most language experts today like the "continuity" ideas. They think language developed step by step. Some believe it came from how early humans sang or made sounds. Others, like Michael Tomasello, think it grew from gestures, like hand movements.

Noam Chomsky, who supports the "discontinuity" idea, thinks a big change happened in humans about 100,000 years ago. He believes a special language ability appeared in one group of humans. This is why, he argues, any baby from anywhere can learn any language perfectly.

Some scientists think language started when humans began to trust each other more. This trust allowed them to use "cheap signals" (words) that could be easily faked. This idea is called "ritual/speech coevolution theory." It suggests that language and human culture, like rituals, grew together. Even chimpanzees have some hidden abilities to use symbols, but they don't use them much in the wild. This theory says that a special social structure with lots of trust was needed for language to work.

Since language started so long ago, there are no direct clues left behind. But we can learn from new sign languages that appear today, like Nicaraguan Sign Language. We can also look at old human bones for signs of how our bodies changed to use language. Scientists also study genes like FOXP2, which might be linked to language. Another way is to look for signs of symbolic behavior, like ancient body-painting, which might be connected to language.

Language probably started somewhere in Africa between 50,000 and 150,000 years ago. This was around the time modern humans first appeared.

Early Ideas About Language

In 1861, a linguist named Max Müller listed some old ideas about how spoken language began:

- Bow-wow theory: This idea said early words came from imitating animal sounds, like "bow-wow" for a dog.

- Pooh-pooh theory: This suggested first words were emotional sounds, like "pooh-pooh" for disgust or "ouch" for pain.

- Ding-dong theory: Müller thought everything had a natural sound or "resonance" that humans copied in their first words.

- Yo-he-ho theory: This idea said language came from sounds made during group work, like "yo-he-ho" when lifting something heavy together.

- Ta-ta theory: Proposed later, this idea said early words came from tongue movements that copied hand gestures.

Today, most experts think these ideas are too simple. They don't explain how sounds got linked to meanings in a complex way.

Long ago, Muslim scholars also had ideas about language origins:

- Naturalist: Language came from humans naturally imitating sounds.

- Conventionalist: Language was made up by people as a social agreement.

- Revelationist: God gave language to humans.

Why Trust is Important for Language

Words are "cheap." This means they are easy to say and can be lies. For language to work, people need to trust that others are usually telling the truth. Animals usually make sounds that are hard to fake, like a cat's purr. This shows they are truly happy. But words can be made up.

Language also lets us talk about things that aren't right in front of us, like something that happened yesterday or far away. This is called "displaced reference." Because of this, language needs a lot of trust to work well.

Mother Tongues Idea

In 2004, W. Tecumseh Fitch suggested that language might have started as "mother tongues." This means language first developed between mothers and their children. Since they are related, they would naturally trust each other more. This trust could have allowed words, which are easy to fake, to become accepted.

Critics say that trust between relatives isn't unique to humans. But Fitch points out that human babies need their parents for a very long time. This long period of closeness could have helped language grow.

Gossip and Grooming Idea

Robin Dunbar suggests that language, especially "gossip," helps humans in large groups. Just like monkeys groom each other to show friendship, humans use language to keep their friendships strong. As human groups got bigger, there wasn't enough time for everyone to groom each other. So, "vocal grooming" (talking) became a faster way to connect. This "vocal grooming" then slowly turned into language and gossip.

Critics wonder how simple "vocal grooming" turned into complex speech.

Ritual and Speech Growing Together

This idea, supported by scholars like Chris Knight, says that language isn't a separate thing. It's part of all human symbolic culture, like rituals, kinship, and religion. They argue that words are "cheap" and can be lies. So, for language to work, people needed to build trust through shared rituals. In hunter-gatherer societies, rituals helped build trust. This trust allowed people to use words, even if they could be false, because everyone agreed to believe them.

Noam Chomsky disagrees with this. He thinks language appeared suddenly and perfectly.

Tools, Brains, and Language

Tools and Language Production

Early humans started making complex stone tools, like Acheulean hand axes, about 1.75 million years ago. Studies show that the same parts of the brain are active when people make these tools and when they produce language. This suggests that the brain skills needed for making tools might have also helped language develop.

Humanistic Theory

This idea sees language as something humans invented. Philosophers like Antoine Arnauld believed that humans are social and smart. This pushed them to create language to share ideas. They thought language grew slowly over time.

Ferdinand de Saussure, a linguist, thought that studying how language changes over time (historical linguistics) was important. But he also believed that understanding how a language works at a certain point in time (structural linguistics) was key.

Chomsky's Single-Step Theory

Noam Chomsky and Robert C. Berwick believe language appeared very suddenly, like a crystal forming. They suggest a single, important change happened in the human brain. This change allowed for "digital infinity," meaning we can create endless new sentences from a few words. They think this happened between 200,000 and 60,000 years ago. This quick change might explain why humans spread across the world so fast.

However, some scientists question if a single mutation could cause such a big change.

Romulus and Remus Idea

Neuroscientist Andrey Vyshedskiy proposed this idea. It suggests language developed in two main steps. The first step was a slow growth of simple language with many words, along with the modern speech parts of our body. This happened around 600,000 years ago.

The second step was a quick "Chomskian single step" around 70,000 years ago. This involved a genetic change that slowed down brain development in some children. This allowed these children to create "recursive" parts of language. Recursion means nesting ideas within each other, like "Mary said [Peter likes apples]." These new recursive parts then combined with their parents' simpler language to create modern language.

This idea is supported by how young children learn language and how human lips are shaped.

Gestural Theory

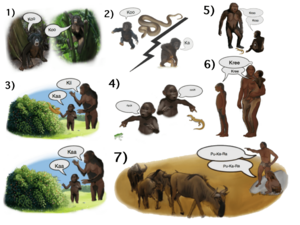

The gestural theory says that human language started from gestures, or hand movements, used for simple communication.

Here's why some support it:

- Brain areas for hand movements and mouth movements are close and work together.

- Apes can use gestures for basic communication, and some of their gestures are like human ones.

- Studies show that sign language and spoken language use similar brain systems.

A big question for this theory is why humans switched from gestures to vocal sounds. Some ideas include:

- Humans started using more tools, so their hands were busy.

- You can't gesture in the dark or if something blocks your view.

- Early language might have been a mix of gestures and sounds, like a "song-and-dance." Later, when trust grew in communities, spoken language became more efficient.

Humans still use gestures when they speak, especially when people don't share a common language. And sign languages, used by Deaf communities, are just as complex as spoken languages.

Critics wonder why early humans would give up effective vocal calls for gestures. But supporters say that animal calls are often not controlled consciously, unlike hand movements.

Sound from Tools and Language

The "Tool-use sound hypothesis" suggests that sounds made when using tools, like hammering, helped language evolve. When early humans walked on two feet, they made rhythmic sounds. This might have helped develop musical abilities and the ability to make complex vocal sounds. Sounds from tools might have become symbols for those tools. This could have led to early words related to tools.

Mirror Neurons and Language

Mirror neurons are special brain cells that activate when you do an action and when you see someone else do the same action. Scientists think these neurons might have helped language evolve. They could help us understand actions, learn by imitating, and understand what others are doing. These neurons are found near Broca's area, a part of the brain important for language.

Some linguists, like Noam Chomsky's supporters, don't think mirror neurons can explain the complex grammar of human language.

Putting-Down-the-Baby Theory

Dean Falk's theory suggests that language started from how early human mothers talked to their babies. Unlike other primates, human babies couldn't cling to their mothers because humans lost their fur. So, mothers had to put their babies down often. To reassure them, mothers developed "motherese"—a way of communicating with facial expressions, body language, touch, and comforting sounds. This interaction, she argues, led to language.

Psychologist Kenneth Kaye agrees that early communication between babies and adults was crucial for language to develop and be passed down.

From-Where-to-What Theory

This idea looks at how our brains process sounds. It suggests seven steps for language evolution. It starts with mothers and babies using contact calls to find each other. These calls then got more complex, adding different tones to show feelings. This led to simple question-and-answer conversations. Over time, unique sounds (phonemes) became linked to objects. Children learned these sounds by watching lip movements. Eventually, humans could put sounds together to make multi-syllable words and then sentences.

This theory is named after two parts of the brain that process sound: the "what" stream (for recognizing sounds) and the "where" stream (for locating sounds). In humans, the "where" stream also handles speech repetition, linking sounds to lip movements, and understanding tones in language.

Speech vs. Language

It's important to know the difference between speech and language. Language doesn't have to be spoken; it can be written or signed. Speech is just one way to share language.

Some experts, like Noam Chomsky, think language first developed in our minds. Then, we learned to "externalize" it (speak, write, or sign) to communicate. A key part of human language, for some, is "recursion"—the ability to put phrases inside other phrases, like "the dog [that chased the cat [that ate the mouse]]."

The ability to ask questions is also seen as special to human language. While some trained apes can answer complex questions, they don't seem to ask questions themselves. Human babies, however, start asking questions with just their voice tone (like raising their voice at the end of a sentence) very early on.

How Our Brains Help Language

Language users can talk about things that aren't right in front of them. This is called "high-level reference." It's linked to "theory of mind," which is knowing that other people have their own thoughts and feelings.

Key parts of this system include:

- Theory of mind: Understanding others' intentions and beliefs.

- Learning concepts: Like knowing the difference between an "object" and a "type" of object.

- Referential vocal signals: Sounds that refer to specific things.

- Imitation: Copying others on purpose.

- Voluntary control over sounds: Being able to make sounds on purpose to communicate.

- Number representation: Understanding numbers.

Theory of Mind

Many scientists believe that having a "theory of mind" was necessary before language could fully develop. Chimpanzees show some of these abilities, but not a complete understanding of false beliefs (knowing someone else might believe something that isn't true). A full theory of mind in humans was a big step towards full language.

Number Understanding

Studies show that animals like rats and pigeons can understand small numbers (less than four) very well. But humans are much better with larger numbers. Children quickly learn that each number is one more than the last. This shows how human language helps us understand numbers in an "open-ended" way.

Language Structure

Lexical-Phonological Principle

This principle describes two important features of human language:

- Productivity: We can create and understand completely new messages. We can combine old words in new ways or give old words new meanings.

- Duality of Patterning: We use a small number of meaningless sounds (like "c," "a," "t") to create a huge number of meaningful words ("cat"). These sounds don't mean anything on their own, but when combined, they create meaning.

Some animals show parts of this. Birdsong has "phonological syntax" (combining sounds into bigger structures), but these structures don't usually create new meanings. Some primates have simple sound systems that refer to things, but they don't combine sounds into new words.

Pidgins and Creoles

Pidgins are simple languages that develop when groups of people who don't share a language need to communicate. They have very basic grammar and a small vocabulary.

If a pidgin is used for a long time and children start learning it as their first language, it can become a creole language. Creoles are much more complex, with full grammar and a larger vocabulary. Interestingly, creole languages often have similar grammar rules, even if they come from very different parent languages. This suggests there might be a natural way humans build language.

Timeline of Language Evolution

Primate Communication

Studying apes in the wild helps us understand early communication. Apes make calls that show their feelings, and it's hard for them to fake these sounds. In captivity, some apes have learned to use sign language or symbols on computers. For example, Kanzi, a bonobo, learned hundreds of symbols.

The Broca's and Wernicke's areas in the primate brain control face, tongue, and mouth muscles, and recognize sounds. These areas are important for human speech.

Vervet monkeys have been studied a lot. They make different alarm calls for different predators, like a "leopard call" or a "snake call." Each call makes the other monkeys react in a specific way.

Early Homo

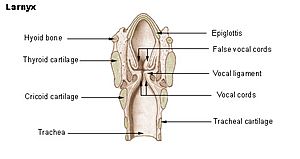

Around 3.5 million years ago, early humans (australopithecines) started walking on two legs. This changed the shape of their skulls and vocal tracts. Some scientists believe these changes were important for making the sounds needed for modern human speech. While Neanderthals might have had similar voice box structures to modern humans, some experts still doubt they had full modern language.

Archaic Homo sapiens

Steven Mithen suggested that early humans, like Homo heidelbergensis and Homo neanderthalensis, used a pre-language system he called Hmmmmm. This system was:

- Holistic (messages were whole ideas, not separate words).

- Manipulative (utterances were commands).

- Multi-modal (used sounds, gestures, and facial expressions).

- Musical.

- Mimetic (imitated things).

Homo erectus

The complex tools made by Homo erectus (around 1 million years ago) suggest they had abstract thought. This kind of thinking is also needed for language. Even if they didn't have complex grammar, their ability to plan and use symbols might show early forms of language.

Homo neanderthalensis

The discovery of a Neanderthal hyoid bone (a small bone in the neck that supports the tongue) suggests they could have made sounds like modern humans. However, some experts, like Richard G. Klein, still doubt they had a fully modern language. He points to their simple stone tools, which didn't change much for a long time. This suggests their brains might not have been complex enough for modern speech.

Computer simulations suggest Neanderthals had a more developed language than simple "proto-language," but not as complex as modern human language. Studies of Neanderthal skulls also suggest they could hear sounds very similar to modern humans, which might mean they had a vocal communication system like ours.

Modern Homo sapiens

Modern humans appeared in Africa about 200,000 years ago. Evidence like the use of red ochre pigments (for rituals and symbols) suggests that modern human bodies and behaviors, including symbolic language, developed together. Around 60,000 to 50,000 years ago, groups of humans left Africa, spreading language and symbolic culture across the world.

The Descended Larynx

The human larynx (voice box) is lower in the neck compared to other primates. This allows us to make a wider range of sounds, especially vowels. This unique feature comes with a cost: it increases the risk of choking. So, scientists wonder what big benefit made this change worthwhile. Many believe it was for speech.

However, some argue that choking is rare, and that speech developed later than the larynx descended. They suggest the larynx might have lowered for other reasons, like making voices sound deeper to appear bigger and more threatening. This is called the "size exaggeration hypothesis."

Phonemic Diversity

In 2011, Quentin Atkinson studied sounds (phonemes) from 500 languages. He found that African languages have the most phonemes, and languages further from Africa have fewer. His research suggests that language originated in western, central, or southern Africa between 80,000 and 160,000 years ago. This fits with the idea that language started around the same time as symbolic culture.

Some linguists disagree with this study, saying it doesn't fully account for how languages change and borrow sounds from each other.

History of Language Research

In Religion and Mythology

Many ancient stories and religions talk about the origin of language. Most don't say humans invented it. Instead, they often say a divine being gave language to humans. For example, in the Bible, the story of the Tower of Babel explains why people speak different languages.

Historical Experiments

Throughout history, some rulers tried to discover the first language by raising children without hearing any words. The Greek historian Herodotus told a story about an Egyptian pharaoh who did this. The children supposedly spoke "bekos," which was the Phrygian word for "bread." King James V of Scotland and others also tried similar experiments. However, these children usually didn't speak, showing that language needs to be learned from others.

Modern Research

Serious study of language origins only really began in the late 18th century. For a long time, it was considered too hard to study. But since the 1950s, interest has grown again. New fields like neurolinguistics (how the brain handles language) and psycholinguistics (how we learn and use language) have helped. Dedicated research groups for the evolution of language only started appearing in the 1990s.

See also

- Animal communication

- Human evolution

- Sign language

- Theory of mind

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |