Prime number facts for kids

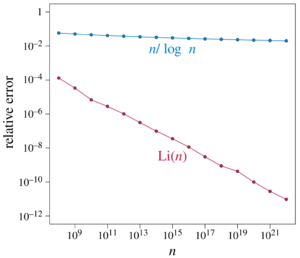

as an approximation to the prime-counting function. The error decreases to zero as

as an approximation to the prime-counting function. The error decreases to zero as  grows.

grows.

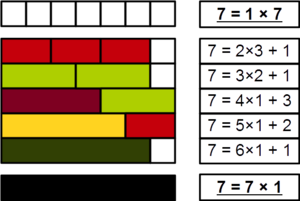

A prime number is a whole number greater than 1 that can only be divided evenly by two things: the number 1 and itself. Think of it like a super-exclusive club where only 1 and the number itself are allowed to be factors!

For example, let's look at the number 5. Can you divide 5 evenly by any number other than 1 and 5? No! 5 divided by 2 leaves a remainder, and so does 5 divided by 3 or 4. So, 5 is a prime number!

On the other hand, a number that is not prime is called a composite number. These numbers have more than two factors. For instance, the number 4 is composite because it can be divided by 1, by 4, AND by 2 (since 2 x 2 = 4). The number 6 is also composite because it can be divided by 1, 6, 2, and 3 (since 2 x 3 = 6).

Contents

- The Special Case of Number 1

- The First Few Primes

- Prime Numbers: The Building Blocks of All Numbers

- A Journey Through Time: The History of Primes

- Endless Primes

- Unsolved Mysteries: Puzzles About Primes

- Checking if a Number Is Prime

- Breaking Numbers Apart: Factorization

- Primes in Everyday Tech

- The Largest Known Primes

- Interesting Facts about Prime Numbers

- Images for kids

- See also

The Special Case of Number 1

You might be wondering about the number 1. Is it prime? Well, according to the rules, a prime number must be greater than 1. Also, prime numbers have exactly two factors: 1 and themselves. The number 1 only has one factor (itself!), so it doesn't quite fit the definition. That's why 1 is considered a very special number, but not a prime number.

The First Few Primes

Let's list some of the first prime numbers. Can you guess them? The first 25 prime numbers (all the primes less than 100) are: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71, 73, 79, 83, 89, 97.

Did you notice something interesting about that list? The number 2 is the only even prime number! That's because any other even number (like 4, 6, 8, 10, and so on) can always be divided by 2, which means it would have more than two factors (1, itself, and 2!). So, all prime numbers after 2 are odd.

Prime Numbers: The Building Blocks of All Numbers

Prime numbers are super important in math because they are like the "basic building blocks" for all other whole numbers (numbers greater than 1). This amazing idea is called the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic. It says that every whole number greater than 1 is either a prime number itself, or it can be broken down into a unique set of prime numbers multiplied together.

The number 10 can be built from 2 and 5 (2 x 5 = 10). The number 12 can be built from 2, 2, and 3 (2 x 2 x 3 = 12). The number 50 can be built from 2, 5, and 5 (2 x 5 x 5 = 50).

No matter how you try to break down a number, you'll always end up with the same set of prime building blocks! This unique way of breaking down a number is called its prime factorization.

A Journey Through Time: The History of Primes

People have been fascinated by prime numbers for a very long time!

Ancient Greece (around 300 BC)

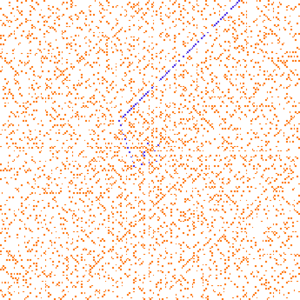

One of the earliest and most famous mathematicians, Euclid, from ancient Greece, wrote a book called "Elements." In it, he proved something incredible: there are infinitely many prime numbers! This means the list of primes never, ever ends. He also showed how to find prime numbers using a clever method called the Sieve of Eratosthenes, named after another Greek mathematician. This "sieve" helps you find primes by systematically crossing out composite numbers from a list.

Medieval Islamic Scholars (around 1000 AD)

Mathematicians like Ibn al-Haytham (also known as Alhazen) and Ibn al-Banna' al-Marrakushi continued to explore prime numbers, finding new ways to test if a number was prime and making the Sieve of Eratosthenes even faster.

European Renaissance (1600s-1700s)

Pierre de Fermat (a French mathematician) studied special types of prime numbers, including "Fermat numbers." Marin Mersenne (another French mathematician) focused on "Mersenne primes," which are primes that are one less than a power of two (like 2^p - 1, where 'p' is also a prime). Christian Goldbach (a German mathematician) proposed a famous puzzle called "Goldbach's Conjecture" in a letter to Leonhard Euler (a Swiss mathematician) in 1742. Euler himself made many important discoveries about primes, including another proof that there are infinitely many of them.

Endless Primes

Euclid's proof that there are infinitely many primes is super clever and easy to understand! Imagine, just for a moment, that there is a final, biggest prime number. Let's call it "P." So, you have a list of all the prime numbers, from 2 all the way up to P.

Now, Euclid said, "Let's multiply all these primes together, and then add 1 to the result." So, you'd have (2 x 3 x 5 x ... x P) + 1.

What about this new number?

It's definitely bigger than P, our supposed "biggest prime." If you try to divide this new number by any of the primes on your list (2, 3, 5, ... P), you'll always get a remainder of 1! This means our new number isn't divisible by any of the primes on our "complete" list.

So, this new number must either be a brand-new prime number itself (one that wasn't on our list!), or it must be divisible by a prime number that also wasn't on our list. Either way, we've found a prime number that wasn't on our original "complete" list! This shows that no matter how many primes you list, you can always find another one. The list of primes truly never ends!

Unsolved Mysteries: Puzzles About Primes

Even with all the smart mathematicians throughout history, there are still many mysteries about prime numbers that no one has solved yet! These are called "conjectures" – ideas that seem true but haven't been proven.

Goldbach's Conjecture

Remember Christian Goldbach? His famous puzzle says that every even number greater than 2 can be written as the sum of two prime numbers. For example:

4 = 2 + 2 10 = 3 + 7 (or 5 + 5) 20 = 3 + 17 (or 7 + 13) Mathematicians have checked this for numbers up to incredibly huge sizes (like 4 followed by 18 zeros!), and it always holds true. But no one has found a way to prove it works for all even numbers!

Twin Prime Conjecture

A "twin prime" pair is two prime numbers that are only 2 apart, like (3, 5), (5, 7), (11, 13), (17, 19), and (29, 31). The Twin Prime Conjecture asks: Are there infinitely many of these twin prime pairs? It seems like there are, but proving it is another big challenge!

Checking if a Number Is Prime

The simplest way to check if a number  is prime is called trial division. You try dividing

is prime is called trial division. You try dividing  by every whole number starting from 2, up to the square root of

by every whole number starting from 2, up to the square root of  . If any of these numbers divide

. If any of these numbers divide  evenly (with no remainder), then

evenly (with no remainder), then  is composite. If none of them do, then

is composite. If none of them do, then  is prime.

is prime.

For example, to check if 37 is prime, you'd try dividing it by 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 (since the square root of 37 is about 6.08). Since 37 isn't evenly divisible by any of these, it's prime!

This method works, but it's too slow for very large numbers. Modern computers use much faster methods.

Breaking Numbers Apart: Factorization

Finding the prime factors of a composite number is called factorization. This is much harder than just checking if a number is prime. While there are many factorization algorithms, they are generally slower than primality tests.

The difficulty of factoring very large numbers is what makes many modern security systems work. For example, the RSA encryption system relies on the fact that it's easy to multiply two large prime numbers together, but incredibly difficult to figure out those two original primes if you only have their product.

Primes in Everyday Tech

Prime numbers are used in many parts of computer science:

- Cryptography: They are essential for keeping online communications and data secure.

- Hash Tables: These are data structures used in computers to store and quickly retrieve information. Using prime numbers for certain sizes or calculations helps them work more efficiently.

- Checksums: These are codes used to check for errors in data. For example, the numbers in International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs) use a calculation involving the prime number 11 to detect mistakes.

- Random Numbers: Prime numbers are also used in creating pseudorandom number generators, which are algorithms that produce sequences of numbers that appear random, useful for simulations and games.

The Largest Known Primes

Here are some of the largest known primes of different types:

| Type | Prime | Number of decimal digits | Date | Found by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mersenne prime | 2136,279,841 − 1 | 41,024,320 | October 12, 2024 | Luke Durant, Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search |

| Proth prime | 10,223 × 231,172,165 + 1 | 9,383,761 | October 31, 2016 | Péter Szabolcs, PrimeGrid |

| factorial prime | 208,003! − 1 | 1,015,843 | July 2016 | Sou Fukui |

| primorial prime | 1,098,133# − 1 | 476,311 | March 2012 | James P. Burt, PrimeGrid |

| twin primes | 2,996,863,034,895 × 21,290,000 ± 1 | 388,342 | September 2016 | Tom Greer, PrimeGrid |

Interesting Facts about Prime Numbers

- As of October 2026, the largest known prime number is 2136,279,841 − 1. This number is so huge it has 41,024,320 decimal digits! It was discovered by Luke Durant as part of the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search (GIMPS) project, which uses many computers around the world working together.

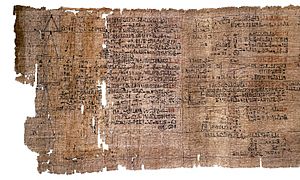

- People have been studying prime numbers for a very long time! The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian text from around 1550 BC, shows some early ideas about numbers.

- According to the prime number theorem, as numbers get bigger, primes become less common, but they never truly run out.

- In the natural world, some insects called cicadas use prime numbers in their life cycles! These insects spend most of their lives underground as grubs. They only come out to breed after 7, 13, or 17 years. Biologists think these prime-numbered cycles help them avoid predators. If a predator had a life cycle that was a multiple of, say, 2 or 3 years, it would be harder for them to sync up with the cicadas' prime-numbered cycles.

- The French composer Olivier Messiaen used prime numbers in his music to create unique and unpredictable rhythms.

- In the science fiction novel Contact by Carl Sagan, scientists try to communicate with aliens using prime numbers as a universal language.

- The novel The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time uses prime numbers to number its chapters, reflecting the main character's mathematical mind.

- In the novel The Solitude of Prime Numbers, primes are used as a metaphor for loneliness, portraying them as "outsiders" among other numbers.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Número primo para niños

In Spanish: Número primo para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |