Raphael Morgan facts for kids

Robert Josias "Raphael" Morgan (born around 1866 – died July 29, 1922) was a Jamaican-American. Many believe he was the first Black Eastern Orthodox priest in the United States. Before joining the Orthodox Church, Morgan was active in other Christian groups. These included the AME Church, the Church of England, and the Episcopal Church.

Morgan became an Orthodox priest for the Ecumenical Patriarchate. He was given the special title of "Missionary to America and the West Indies." He also said he started something called the "Order of Golgotha." However, the Orthodox Church does not have such orders.

As a young man, he traveled a lot in the Caribbean and the United States. He became a minister in the AME Church, which was the first independent Black church in the US. Later, he went to England and joined the Church of England. He began studying religion there. He returned to the US and became an Episcopal priest in 1895. He continued his studies and worked in several churches.

Morgan never became fluent in Greek, which is a main language of the Eastern Orthodox Church. He usually led his church services in English. People only rediscovered his life story in the late 1900s. Since then, he has been a topic of study. Still, much of his life is not well known and remains a mystery. A short story about him from 1915 said he had lived all over the world.

Early Life and Travels

Robert Josias Morgan was born in Chapelton, Jamaica. This was in the late 1860s or early 1870s. His parents were Robert Josias and Mary Ann Morgan. He was named after his father, who died before he was born. He grew up in the Anglican faith and went to school nearby.

As a teenager, Morgan traveled to Colón, Panama, and then to British Honduras. He went back to Jamaica, and then to the United States. In the US, he became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). This was the first independent Black church in the United States. He also traveled to Germany as a missionary.

Joining the Church of England

Morgan later went to England. There, he joined the Church of England. He was sent to Sierra Leone, a colony in West Africa. He worked at the Church Missionary Society Grammar School in Freetown. He studied advanced subjects like Greek and Latin there. Morgan also worked as a second master at a public school in Freetown. He took courses at Fourah Bay College in Freetown.

Sierra Leone was created in the late 1700s. It was a place for Black people from London to settle. Many of them were Black Loyalists who had been freed by the British during the American Revolutionary War. Others came from Nova Scotia, Jamaica, or were freed from slave ships.

Morgan was then appointed as a missionary teacher. He also worked as a lay-reader by Bishop Samuel David Ferguson. Bishop Ferguson was an Episcopal Bishop in Liberia. Liberia is a country next to Sierra Leone. Morgan later said he served five years in West Africa. Three of those years were spent doing missionary work. Liberia was a colony for free Black people from the United States.

After returning to England for private study, Morgan went to the United States. He worked as a lay reader in the African-American community. He was accepted as a candidate to become an Episcopal deacon. During the waiting period before becoming a deacon, Morgan went back to England. He was said to have studied at Saint Aidan's Theological College. He also completed studies at King's College London. However, these colleges do not have records of him attending.

Serving in the Episcopal Church

Morgan returned to the United States. He became a deacon on June 20, 1895. Bishop Leighton Coleman, who opposed racism, ordained him. Morgan worked at St Matthews' Church in Wilmington, Delaware, from 1896 to 1897. He also taught in public schools in Delaware. From 1897, he served the Episcopal Church in Charleston, West Virginia.

In 1898, Morgan moved to Asheville, North Carolina. By 1899, he was an assistant minister. He served at St. Stephen's Chapel in Morganton, North Carolina. He also served at St. Cyprian's Church in Lincolnton, North Carolina.

In 1901-1902, Morgan visited his home country, Jamaica. In October 1901, he spoke about West Africa and missionary work. In October 1902, he gave a lecture in Port Maria. It was called "Africa - Its People, Tribes, Idolatry, Customs."

Between 1900 and 1906, Morgan moved around the Eastern US. He served in Richmond, Virginia (1902-1905). He was in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1905. By 1906, he was in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His address was the Church of the Crucifixion.

During this time, Morgan joined the American Catholic Church (ACC). This was a group related to the Episcopal Church. Morgan was listed in Episcopal Church records until 1908.

Becoming Orthodox

Journey to Russia

Around the early 1900s, Morgan started to question his faith. For three years, he studied Anglicanism, Catholicism, and Eastern Orthodoxy. He was looking for what he called the "true religion." He decided that the Eastern Orthodox Church was "the pillar and ground of truth." He left the Episcopal Church. In 1904, he began a long trip to the Russian Empire.

In Russia, Morgan visited many monasteries and churches. He went to Odessa, St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Kiev. As a Black American, he attracted a lot of attention. Newspapers started publishing his pictures and stories. Soon, Morgan became a special guest of the Tsar. He was allowed to attend celebrations for Tsar Nicholas II's coronation. He also attended a memorial service for the late Emperor Alexander III.

After Russia, Morgan traveled to the Ottoman Empire, Cyprus, and the Holy Land. When he returned to the US, he wrote an open letter. It was published in the Russian-American Orthodox Messenger in 1904. He wrote about his experiences in Russia. He hoped the Episcopal Church could unite with the Orthodox Churches. Morgan continued his spiritual search.

Study and Trip to Constantinople

For three more years, Morgan studied with Greek priests in the United States. He was preparing for baptism. He decided to join the Greek Orthodox Church and become a priest. In January 1906, he helped with the Christmas church service. In 1907, the Greek community in Philadelphia sent Morgan to the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople. They sent two letters supporting him.

Father Demetrios Petrides, the Greek priest in Philadelphia, wrote one letter. He said Morgan was sincere in wanting to join Orthodoxy. He recommended Morgan's baptism and ordination. The second letter was from the Philadelphia Greek Orthodox Church committee. They said Morgan could be an assistant priest if he could not start a separate church for Black Americans.

In Constantinople, Morgan was interviewed by Metropolitan Joachim (Phoropoulos). Metropolitan Joachim was one of the few bishops who spoke English. He found that Morgan had "deep knowledge of the teachings of the Orthodox Church." He also had a certificate from the Methodist Community. It said Morgan was a man "of high calling and of a religious life." The Metropolitan agreed to his baptism.

Baptism and Ordination

On August 2, 1907, the Holy Synod approved Morgan's baptism. It was to happen the next Sunday. The baptism took place at the Church of the Life-giving Source in Constantinople. Metropolitan Joachim officiated the baptism. Bishop Leontios was his sponsor. On Sunday, August 4, 1907, Robert was baptized "Raphael" in front of 3000 people.

He was then ordained a deacon on August 12, 1907, by Metropolitan Joachim. Finally, he became a priest on August 15, 1907. This was on the feast day of the Dormition of the Theotokos. A newspaper called L'Echo d' Orient reported on the event. It said the Metropolitan performed the baptism and ordination in English. Father Raphael then chanted the Divine Liturgy in English. With this, Father Raphael Morgan became the first African-American Orthodox priest.

Father Raphael was sent back to the US. He received church clothes, a cross, and money for his travel. He was allowed to hear confessions. However, he was not given Holy Chrism or an antimension. This was likely to keep his missionary work connected to the Philadelphia church. The Holy Synod minutes from October 2, 1907, stated that Father Raphael would be under the priest in Philadelphia. Once he was fully trained and could start his own church, he could become independent.

Return to America

Father Raphael Morgan arrived in New York in December 1907. He baptized his wife and children into the Orthodox Church.

The last mention of Father Raphael in church records is from November 4, 1908. He wrote a letter recommending an Anglican priest. This priest, "A.C.V. Cartier," wanted to convert to Orthodoxy. Cartier was the leader of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia. This church served important African-American families. It was started in 1794 by Absalom Jones.

Father Raphael and his wife divorced in 1910. Father Raphael kept custody of their 13-year-old daughter, Roberta Viola Morgan. Their 9-year-old son, Cyril Ignatius, lived with his mother.

Monastic Life and Lectures

In 1911, Morgan sailed to Cyprus. He may have become a monk there. Some suggest he became a monk in Athens in 1911. Around this time, he claimed to have started the "Order of the Cross of Golgotha." However, there are no records of this in the Church of Greece.

An article from April 1913 said Father Raphael was based in Philadelphia. He wanted to build a chapel for his missionary work. It reported he had recently visited Europe to raise money. He also planned to expand his work to the West Indies.

Near the end of 1913, Father Raphael visited his home, Jamaica. He stayed for several months. While there, he met a group of Syrians. They were upset because there were no Orthodox churches on the island. Father Raphael tried to contact the Syrian-American diocese of the Russian church. He wrote to St. Raphael of Brooklyn. In December, a Russian warship came to port. He led a church service with the sailors, their chaplain, and the Syrians.

Morgan mostly gave lectures throughout Jamaica. Since there were no Orthodox churches, he spoke in churches of other faiths. He talked about his travels, the Holy Land, and Holy Orthodoxy. He returned to Chapelton, where he told people, "I will always be Robert to you."

According to a newspaper from November 2, 1914, Father Raphael had sailed for America. He planned to start missionary work there.

Later Life and Passing

A short biography from 1915 said Morgan had lived all over the world. This included Palestine, Syria, Greece, Russia, England, France, and the United States.

In 1916, Father Raphael was still in Philadelphia. He used the Philadelphia Greek church as his base. The last known record of Father Raphael is a letter. It was sent to the Daily Gleaner on October 4, 1916. He represented a group of Jamaican-Americans. They wrote to protest the lectures of Black Nationalist Marcus Garvey. They felt Garvey's views harmed their homeland's reputation. Garvey said the letter was a trick to hurt his success.

Little is known about Father Raphael's later life. The Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America does not have records of him or Father Demetrios Petrides. Records for the Philadelphia church only start in 1918.

Morgan's daughter said on her passport that her father died between 1916 and 1924. In the 1970s, a historian interviewed people from the Greek community in Philadelphia. They remembered the Black priest. One person said Father Raphael's daughter went to Oxford University. Another recalled that Morgan spoke some Greek but mostly led services in English. Someone else remembered that Father Raphael left for Jerusalem and never returned.

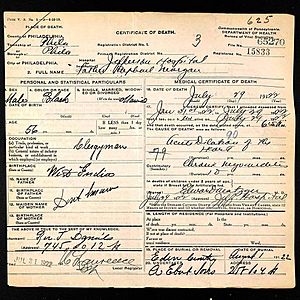

Father Raphael Morgan passed away on July 29, 1922, in Philadelphia. He was 56 years old. He is buried in Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania. He had a simple funeral and was buried quietly.

His Impact

Connecting with George McGuire

In 2009, Matthew Namee gave a lecture about Father Raphael Morgan. He suggested that Father Raphael might have influenced thousands of people to become Orthodox. This could have happened through his contact with an Episcopal priest named George Alexander McGuire. McGuire later founded the African Orthodox Church in 1921.

Namee wondered why McGuire decided to form an Orthodox church. Father Raphael Morgan and George McGuire had many things in common:

- Both worked at St Philip's Episcopal Church in Virginia.

- Both became priests in the Episcopal Church around the same time.

- Both later served in Philadelphia.

- Both had some contact with Reverend A. C. V. Cartier.

Namee believes these similarities mean the two men likely knew each other. He thinks McGuire was inspired by Father Raphael. This inspiration could have led McGuire to learn about the Orthodox Church.

Also, Marcus Garvey knew about Father Raphael Morgan. McGuire joined Garvey's group in 1920. This makes it likely that McGuire and Garvey discussed Morgan.

However, McGuire might have learned about the Eastern Orthodox Church from Joseph René Vilatte. Vilatte was the one who made McGuire a bishop. Vilatte had contact with both the Russian and Syriac Orthodox Churches.

The African Orthodox Church

George McGuire became involved with Marcus Garvey's Black Nationalist movement. He was appointed the first Chaplain-General of Garvey's organization in 1920. On September 28, 1921, McGuire became a Bishop of the American Catholic Church. He then founded the African Orthodox Church (AOC). This church was a Black Nationalist church.

Bishop McGuire quickly spread his African Orthodox Church. It grew across the United States and even in Africa. Branches were set up in Canada, Barbados, Cuba, and several US cities. The church's newspaper, The Negro Churchman, helped connect its members. Around World War II, the African churches were cut off from the American ones. After the war, they joined the Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria. In 1946, the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria officially recognized these African churches.

Father Raphael's Legacy

Historian Gavin White wrote in the 1970s. He said that if Morgan tried to start a Black Greek Orthodox church in Philadelphia, its memory is gone. But he added that McGuire likely knew Morgan personally. White believed Morgan probably introduced McGuire to the idea of Eastern Orthodoxy.

Matthew Namee also concluded that Father Raphael inspired McGuire to form an "Orthodox" church. In 1946, the African parts of McGuire's church joined the Patriarchate of Alexandria. Orthodox Christianity seemed appealing to East Africans. This was because it was not linked to racism or colonialism.

Father Raphael Morgan's work among Jamaicans in Philadelphia may have been short-lived. However, he might have sparked interest in Orthodoxy for some African Americans today.

See also

- List of African-American firsts

- List of Eastern Orthodox missionaries

- George Alexander McGuire

- African Orthodox Church

- Joseph René Vilatte

- Albert J. Raboteau

- Religion in Black America

Sources

Contemporary sources

- ATOR (African Times and Orient Review), (February – March 1913), p. 163.

- Bragg, Rev. George F. (D.D.). "Chapter XXXVI: Negro Ordinations from 1866 to the Present". In: History of the Afro-American group of the Episcopal church (1922). Baltimore, Md.: Church Advocate Press, 1922.

- Bragg, Rev. George F. (D.D.). "Afro-American Clergy List. Priests". In: Afro-American Church Work and Workers. Baltimore, Md.: Church Advocate Print, 1904.

- Hill, Robert A., Marcus Garvey, Universal Negro Improvement Association. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers: 1826-August 1919. University of California Press, 1983. ISBN: 978-0-520-04456-2

- Mather, Frank Lincoln. Who's Who of the Colored Race: A General Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women of African Descent. University of Michigan. Gale Research Co., 1915, pp. 226–227.

- R. J. Morgan. "An Open Letter." Amerikanskiĭ Pravoslavnyĭ Viestnik. October and November Supplement (1904), pp. 380–82.

- The Daily Gleaner. West Africa. October 9, 1901, p. 7.

- The Daily Gleaner. November 2, 1914, p. 13.

- "Une Conquete du Patriarcat Oecumenique". Échos d'Orient, Vol. XI. No. 68, 1908, pp. 55–56.

- (Publication of the Roman Catholic Uniate Assumptionist Fathers, located in Chalcedon; for an online translation of the French article, see: Fr. Andrew S. Damick. '"The Sorcerer on the Golden Horn." OrthodoxHistory.org (The Society for Orthodox Christian History in the Americas), December 15, 2009)

- Work, Monroe N. (ed.). The Negro Yearbook, an Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro, 1921-1922. The Negro Year Book Publishing Company: Tuskegee Institute, 1922 (1921 edition, p. 213)

Modern sources

- Herbel, Fr. Oliver (OCA). "Jurisdictional Disunity and the Russian Mission". Orthodox Christians for Accountability. April 22, 2009.

- Herbel, Fr. Oliver (OCA). "Morgan, Raphael". The African American National Biography at mywire.com. 1 January 2008.

- Herbel, Fr. Oliver (OCA). "Turning to Tradition: Intra-Christian Converts and the Making of an American Orthodox Church." Ph.D. Dissertation, under the direction of Michael McClymond (2009). 349 pp.

- Herbel, Fr. Oliver (OCA). "The Relationship of the African Orthodox Church to the Orthodox Churches and Its Importance for Appreciating the Brotherhood of St. Moses the Black," Black Theology. (forthcoming)

- Kourelis, Kostis. "Philadelphia Greeks and Their Black Priest." Objects-Building-Situation: Musings on Architecture, Art and History, with Special Focus on Mediterranean Archaeology. Thursday, October 29, 2009.

- Lumsden, Joy, MA (Cantab), PhD (UWI). Father Raphael.

- Lumsden, Joy. "Robert Josias Morgan, aka Father Raphael". Jamaican History Month 2007. 16 February 2007.

- Manolis, Paul G. "Raphael (Robert) Morgan: The First Black Orthodox Priest in America". Theologia: Epistēmonikon Periodikon Ekdidomenon Kata Trimēnian. (En Athenais: Vraveion Akadēmias Athēnōn), 1981, vol. 52, no.3, pp. 464–480. ISSN 1105-154X

- Martin, Tony. "McGuire, George Alexander". Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. Volume 2. Cary D. Wintz, Paul Finkelman (eds). Taylor & Francis, 2004.

- Namee, Matthew. "Fr. Raphael Morgan: America's First Black Orthodox Priest". 16th Annual Ancient Christianity & African-American Conference, June 3, 2009.

- Namee, Matthew. "The First Black Orthodox Priest in America". OrthodoxHistory.org (The Society for Orthodox Christian History in the Americas). July 15, 2009.

- Namee, Matthew. "Robert Josias Morgan visits Russia, 1904". OrthodoxHistory.org (The Society for Orthodox Christian History in the Americas). September 15, 2009.

- Namee, Matthew. "Fr. Raphael Morgan against Marcus Garvey". OrthodoxHistory.org (The Society for Orthodox Christian History in the Americas). March 29, 2010.

- White, Gavin. Patriarch McGuire and the Episcopal Church. In: Randall K. Burkett and Richard Newman (eds). Black Apostles: Afro-American Clergy Confront the Twentieth Century. G. K. Hall, 1978, pp. 151–180.

- '

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |