Religion of Black Americans facts for kids

The religion of Black Americans includes the spiritual practices of African Americans. Many historians agree that religious life forms the basis of their community. Before 1775, there was little organized religion among Black people in the Thirteen Colonies.

The Methodist and Baptist churches became very active in the 1780s. Their membership grew quickly for the next 150 years. Eventually, most Black Americans joined these churches. After slavery ended in 1863, freed people formed their own churches. Most were Baptist, followed by Methodists. Other Christian groups and the Catholic Church were less common.

In the 19th century, the Holiness movement was important. Later, Pentecostalism in the 20th century and Jehovah's Witnesses also grew. The Nation of Islam and Malcolm X brought Islam into the picture in the 20th century. Powerful pastors often played big roles in politics. They led the American Civil Rights Movement, like Martin Luther King Jr., Jesse Jackson, and Al Sharpton.

Contents

How Many Black Americans Are Religious?

Religious groups of African Americans Black Protestant (59%) Evangelical Protestant (15%) Mainline Protestant (4%) Roman Catholic (5%) Jehovah's Witness (1%) Other Christian (1%) Muslim (1%) Other religion (1%) Unaffiliated (11%) Atheist or agnostic (2%)

Most Black Americans are Protestants. Many are descendants of enslaved people. They are mostly Baptists or other Evangelical Protestants. A 2007 survey found that Black Americans were more religious than the general U.S. population. About 87% of Black Americans belonged to a religion. This compares to 83% of the wider population.

About 79% of Black Americans said religion was "very important" in their lives. Only 56% of other U.S. people felt this way. About 83% of Black Americans identified as Christian. This included 45% who were Baptist. Catholics made up 5% of the population. About 1% of Black Americans identified as Muslims. Around 12% of Black Americans did not identify with a religion. This was slightly lower than for the whole U.S.

In 2019, there were about three million African American Catholics in the U.S. About 24% of them worshipped in the country's 798 mostly African American churches.

History of Black American Religion

Africans brought their religions with them to America. These included Islam, Catholicism, and traditional African beliefs. In the 1770s, less than 1% of Black people in the U.S. were part of organized churches. This number grew fast after 1789. The Church of England tried to spread Christianity, but did not get many converts.

No organized African religious practices are known to have continued openly in the Thirteen Colonies. Scholars used to debate if African elements were hidden in Black American religious practices. Now, they do not look for such direct links in religion.

Muslims practiced Islam secretly during slavery in North America. The story of Abdul Rahman Ibrahima Sori shows this. He was a Muslim prince from West Africa. He was enslaved for 40 years in the U.S. before being freed. His story proves that Muslim beliefs survived among enslaved Africans.

Before the American Revolution, masters and preachers shared Christianity with enslaved people. This included Catholicism in Spanish Florida and Louisiana. Protestantism spread in English colonies.

Early Churches and Freedom

During the First Great Awakening (around 1730–1755), Baptists attracted many people in Virginia. They welcomed enslaved people to their services. Some Baptist groups had up to 25% enslaved members. Baptists and Methodists from New England spoke out against slavery. They encouraged masters to free their slaves. They also converted enslaved and free Black people. They gave them active roles in new churches.

The first independent Black churches started in the South before the Revolution. These were in South Carolina and Georgia. Many Christians, especially in the North, believed slavery was wrong. They helped with the Underground Railroad. This was a network that helped enslaved people escape. Wesleyan Methodists, Quakers, and Congregationalists were especially involved. White preachers in evangelical Protestantism taught that all Christians were equal to God. This gave hope to enslaved people.

As slavery grew in the South, some Baptist and Methodist ministers changed their views. After 1830, white Southerners argued that Christianity and slavery could exist together. They used Bible verses to support this. They said Christianity encouraged better treatment of slaves. In the 1840s and 1850s, slavery split the largest religious groups. The Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian churches divided into Northern and Southern branches.

Southern enslaved people often went to their masters' white churches. They usually sat in the back. White preachers told them to stay in their place. They also taught masters to treat slaves "justly and fairly." This meant masters should control their anger and set a good example.

Enslaved people also held their own secret religious meetings. Larger plantations with many slaves were often places for these nighttime gatherings. These groups had a preacher, often someone who could not read. These preachers were known for their strong faith. Black Americans developed beliefs based on Bible stories that meant a lot to them. These included the hope for freedom, like the Exodus story. A lasting result of these secret meetings is the African American spiritual. Black religious music is different from European religious music. It uses dances and ring shouts. It also focuses more on emotion and repetition.

How Black Churches Formed

Scholars debate how much African culture shaped Black Christianity in the 18th century. But it is clear that Black Christianity was based on evangelicalism. The black church was key to building community among Black people. It was usually the first community group they formed. Starting around 1800, with the African Methodist Episcopal Church and others, the Black church became the main focus of the Black community. It showed their unique spirit and was a response to unfair treatment.

Churches also served as community centers. Free Black people could celebrate their African heritage there. Churches also helped with education. They taught both freed and enslaved Black people. Some Black religious leaders, like Richard Allen, started separate Black churches to gain independence. The Second Great Awakening (1800–1820s) was very important for the growth of Black Christianity. Free Black religious leaders also started Black churches in the South before 1860. After the First Great Awakening, many Black Christians joined the Baptist Church. This church allowed them to participate, even as leaders and preachers. For example, First Baptist Church and Gillfield Baptist Church in Petersburg, Virginia, had organized groups by 1800.

The Role of Preachers

Historian Bruce Arnold says that successful Black pastors have always had many roles. They are like the head of their church family. They guide the community and share its history. They are spiritual leaders and wise advisors. Black pastors also comfort people during hard times. They help people protect themselves from sadness. They are also community organizers. They connect people and groups.

Raboteau describes a common style of Black preaching. It started in the early 1800s and is still common today. The preacher starts calmly, speaking clearly. Then, they speak faster and more excitedly. They begin to chant their words to a rhythm. Finally, they reach an emotional high point. The chanted speech becomes musical and mixes with the singing, clapping, and shouting of the church members.

Many Americans saw big events through a religious lens. Historian Wilson Fallin compares how white and Black Baptist preachers in Alabama explained the American Civil War. White Baptists believed God had tested them. They thought God wanted them to keep strict Bible rules and traditional race relations. They said slavery was not a sin. They saw the end of slavery as a tragedy. They saw the end of Reconstruction as a sign of God's favor.

Black Baptists saw the Civil War and the end of slavery differently. They saw them as God's gift of freedom. They liked being able to worship in their own way. They felt their worth and dignity were affirmed. They could form their own churches and groups. These groups helped them and their communities. They were places where the message of freedom could be preached. Black preachers kept saying that God would protect and help them.

Sociologist Benjamin Mays studied sermons in the 1930s. He found that they often encouraged Black people to be calm about life. They supported the idea that God would fix things in His own time. They made Black people feel that God would make things right. If not in this world, then in the next. They saw God as mainly helping in the afterlife. He would prepare a home for those who suffered on Earth.

After Slavery Ended (1865)

After slavery ended, Black Americans actively formed their own churches. Most were Baptist or Methodist. They gave their ministers important moral and political leadership roles. Almost all Black Americans left white churches. Few mixed-race churches remained. Four main groups competed to form new Methodist churches for freed people. These were the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, and the Methodist Episcopal Church (Northern white Methodists). By 1871, Northern Methodists had 88,000 Black members in the South. They also opened many schools for them.

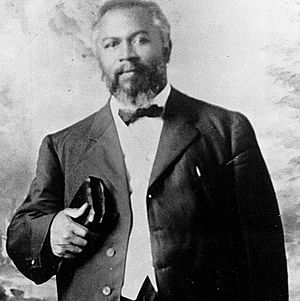

During Reconstruction, Black Americans were key to the Republican Party. Ministers had strong political roles. They did not rely on white support, unlike teachers or business people. Charles H. Pearce, an AME minister in Florida, said a minister must look out for his people's political interests. Over 100 Black ministers were elected to state legislatures during Reconstruction. Several served in Congress. One, Hiram Rhodes Revels, served in the U.S. Senate.

City Churches and Their Role

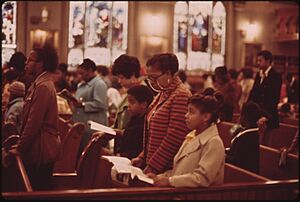

Most Black Americans lived in rural areas. Services were held in small, simple buildings. In cities, Black churches were more noticeable. Besides regular services, city churches had many other activities. These included prayer meetings, missionary groups, women's clubs, youth groups, and concerts. Revivals were held for weeks, attracting large crowds.

Churches also did a lot of charity work. They cared for the sick and needy. Larger churches had education programs, like Sunday schools and Bible study. They held classes to help older members learn to read the Bible. Private Black colleges, like Fisk in Nashville, often started in church basements. Churches also supported small Black businesses.

The political role was very important. Churches hosted protest meetings, rallies, and Republican party meetings. Important church members and ministers made political deals. They often ran for office until they lost the right to vote in the 1890s. In the 1880s, banning alcohol was a big political issue. This allowed Black and white Protestants to work together. In every case, the pastor was the main decision-maker. Their salary was good for the time.

Methodists increasingly sought ministers with college degrees. But most Baptists felt that education made ministers less religious. After 1910, many Black people moved to cities in the North and South. This led to a few very large churches with thousands of members. These churches had paid staff and influential preachers. At the same time, there were many small "storefront" churches with only a few dozen members.

Major Black Christian Groups

Methodist Churches

African Methodist Episcopal Church

In 1787, Richard Allen and others in Philadelphia left the Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1816, they founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). It started with 8 clergy and 5 churches. By 1846, it had grown to 176 clergy, 296 churches, and 17,375 members. By 1856, its 20,000 members were mostly in the North. AME membership jumped from 70,000 in 1866 to 207,000 in 1876.

The AME church valued education highly. In the 19th century, the AME Church of Ohio worked with the Methodist Episcopal Church (mostly white). They helped create Wilberforce University in Ohio. This was the second independent historically Black college (HBCU). By 1880, AME ran over 2,000 schools, mostly in the South. They had 155,000 students. They used church buildings as schools. Ministers and their wives were teachers. The churches raised money to keep schools running. This was important because segregated public schools had little money.

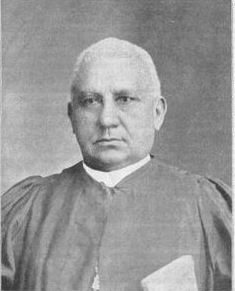

After the Civil War, Bishop Henry McNeal Turner (1834–1915) was a major AME leader. He was also active in Republican Party politics. In 1863, during the Civil War, Turner became the first Black chaplain in the United States Colored Troops. Later, he worked for the Freedmen's Bureau in Georgia. He settled in Macon and was elected to the state legislature in 1868. He started many AME churches in Georgia after the war.

In 1880, he was elected as the first southern bishop of the AME Church. He was angry when Democrats regained power and created Jim Crow laws. Turner became a leader of Black nationalism. He suggested that Black people move to Africa.

Methodist churches usually attracted Black leaders and the middle class. Like all American religious groups, new groups formed often.

African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

The AMEZ church officially formed in 1821 in New York City. It had been active for some years before that. In 1866, it had about 42,000 members. The church started Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina. This college trained missionaries for Africa. Today, the AME Zion Church is very active in mission work. They work in Africa and the Caribbean, including Nigeria, Liberia, and Jamaica.

Wesleyan-Holiness Movement

The Holiness movement started within the Methodist Church in the late 1800s. It focused on the Methodist idea of "Christian perfection." This means believing it is possible to live without willingly sinning. It also means this can happen instantly through a "second work of grace." Many in the holiness movement stayed in the main Methodist Church. But new groups also formed, like the Free Methodist Church and Church of God (Anderson, Indiana). The Wesleyan Methodist Church was founded to spread Methodist beliefs and support abolitionism.

The Church of God (Anderson, Indiana), started in 1881. They believed that "interracial worship was a sign of the true Church." Both white and Black ministers served in their churches. They invited people of all races to worship together. Those who felt "entirely sanctified" said they were "saved, sanctified, and prejudice removed." When Church of God ministers visited other churches, the rope separating white and Black people was untied. People of both races would pray together at the altar. Even when outsiders attacked their services for racial equality, Church of God members were not stopped. They kept their strong belief in the unity of all believers.

Other Methodist Groups

- African Union First Colored Methodist Protestant Church and Connection

- Christian Methodist Episcopal Church

- Church of Christ (Holiness) U.S.A.

- Lumber River Conference of the Holiness Methodist Church

Baptist Churches

After the Civil War, Black Baptists wanted to practice Christianity without racial discrimination. They quickly set up separate churches and state Baptist groups. In 1866, Black Baptists from the South and West formed the Consolidated American Baptist Convention. This group eventually broke apart. But three national conventions formed in its place. In 1895, these three groups joined to create the National Baptist Convention. It is now the largest African-American religious group in the United States.

From the late 1800s until today, most Black Christians belong to Baptist churches. Baptist churches are controlled by their local members. They choose their own ministers. They pick local men, often young, known for their faith and preaching skills. Few were well-educated until the mid-1900s. Most were farmers or had other jobs. They became spokesmen for their communities. They were among the few Black people in the South allowed to vote during Jim Crow times before 1965.

National Baptist Convention

The National Baptist Convention started in 1880. It was first called the Foreign Mission Baptist Convention in Montgomery, Alabama. Its founders, like Elias Camp Morris, believed preaching the gospel could fix problems in segregated churches. In 1895, Morris moved to Atlanta, Georgia. He founded the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc. It was a merger of three groups. This convention is the largest African-American religious organization.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s caused many disagreements in Black churches. Some ministers preached spiritual salvation, not political action. The National Baptist Convention became deeply divided. Its leader, Rev. Joseph H. Jackson, supported the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956. But by 1960, he told his church not to get involved in civil rights.

Jackson was based in Chicago. He was close to Mayor Richard J. Daley. Martin Luther King Jr. and his aide Jesse Jackson Jr. (no relation to Joseph Jackson) disagreed with him. In the end, King led his activists out of the National Baptist Convention. They formed their own group, the Progressive National Baptist Convention. This group supported King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Other Baptist Groups

- Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship

- National Baptist Convention of America, Inc.

- National Missionary Baptist Convention of America

- Progressive National Baptist Convention

Pentecostalism

Black Methodists and Baptists often sought to be seen as middle class. But Holiness Pentecostalism was different. Besides the Holiness Methodist belief in entire sanctification, it also taught a "third work of grace." This experience could empower people to avoid sin. It was often accompanied by glossolalia (speaking in tongues). These groups focused on the direct experience of the Holy Spirit. They also emphasized the emotional worship style common in Black churches.

William J. Seymour, a Black preacher, traveled to Los Angeles. His preaching started the three-year-long Azusa Street Revival in 1906. Worship at the Azusa Mission was very free. People preached and shared their faith as they felt led by the Spirit. They spoke and sang in tongues. They also fell down in the Spirit. The revival attracted a lot of attention. Thousands of visitors came to the mission. They then took the "fire" back to their own churches.

The crowds of Black and white people worshipping together at Seymour's mission set the tone for early Pentecostalism. Pentecostals went against social rules of the time. They defied racial segregation and Jim Crow. Holiness Pentecostal groups were interracial before the 1920s. These included the Church of God in Christ, the Church of God, and the International Pentecostal Holiness Church. These groups faced pressure to follow segregation, especially in the Jim Crow South.

Eventually, North American Pentecostalism split into white and African-American branches. Interracial worship did not become widespread again until after the Civil Rights Movement. The Church of God in Christ (COGIC) is an African American Pentecostal group. It was founded in 1896. Today, it is the largest Pentecostal group in the United States.

Other Pentecostal Groups

- Apostolic Faith Mission

- Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ of the Apostolic Faith

- Fire Baptized Holiness Church of God of the Americas

- Mount Sinai Holy Church of America

- Pentecostal Assemblies of the World

- United House of Prayer for All People

- United Pentecostal Council of the Assemblies of God, Incorporated

Other Religions Among Black Americans

African Religions

Louisiana Voodoo is a mixed religion traditionally practiced by Creoles of color and African Americans in Louisiana. Hoodoo is a system of beliefs and rituals. It is linked to the Gullah people and Black Seminoles. Hoodoo and Voudou are still active religions in African-American communities. Young African Americans are also rediscovering these traditions.

Islam

Historically, between 15% and 30% of enslaved Africans brought to the Americas were Muslims. But most were forced to become Christian during slavery. Islam had spread in Africa through Arab Muslim expansion. Its presence grew stronger through trade and the 1300-year Middle Eastern slave trade of Africans. In the 20th century, many African Americans wanted to reconnect with their African heritage. They converted to Islam. This was mainly due to black nationalist groups with unique beliefs. These included the Moorish Science Temple of America and the Nation of Islam. The Nation of Islam, founded in the 1930s, had at least 20,000 members by 1963.

Famous members of the Nation of Islam included Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. Malcolm X is seen as the first person to start converting African Americans to mainstream Sunni Islam. He left the Nation and made the pilgrimage to Mecca. He changed his name to el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz. In 1975, Warith Deen Mohammed, Elijah Muhammad's son, took over the Nation. He converted most of its members to orthodox Sunni Islam.

African-American Muslims make up 20% of the total U.S. Muslim population. Most Black Muslims are Sunni or orthodox Muslims. A 2014 survey showed that 23% of American Muslims were converts. This included 8% who converted from historically Black Protestant traditions. Other groups claim to be Islamic. These include the Moorish Science Temple of America and its offshoots, like the Five Percenters.

Judaism

The American Jewish community includes Jews with African-American backgrounds. African-American Jews belong to all major American Jewish denominations. These include Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform. There are also African-American Jewish people who are not religious. Estimates of Black Jews in the U.S. range from 20,000 to 200,000. Most Black Jews have mixed ethnic backgrounds. They are Jewish by birth or by converting.

Black Hebrew Israelites

Black Hebrew Israelites are groups of African Americans. They believe they are descendants of the ancient Israelites. Black Hebrews follow some religious beliefs and practices from both Christianity and Judaism. They are not recognized as Jews by the wider Jewish community. Many call themselves Hebrew Israelites or Black Hebrews. This shows their claimed historical connections.

Other Faiths

Some African Americans, mostly converts, follow other faiths. These include the Baháʼí Faith, Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Scientology, and Rastafari. A 2019 report looked at a group of African-American women. They worshipped the African deity Oshun as part of Modern Paganism. Some African Americans practice Louisiana Voodoo, especially in Louisiana. Louisiana Voodoo came to Louisiana from Benin with African slaves during French rule.

See also

- Black theology

- National Black Catholic Congress

- Southern Christian Leadership Conference

- Louisiana black church fires

- African diaspora religions

- Black church

- Atheism in the African diaspora

- Islam in the African diaspora

- African American–Jewish relations

- African-American Jews

- Black Mormons

- Black people and Mormonism

- Black Catholicism

- T. D. Jakes

- Christian hip hop

- Black Gospel music

- Louisiana Voodoo

History:

- Methodist Episcopal Church, South

- Wesleyanism

- Colored Episcopal Mission

- Racial segregation of churches in the United States

- Religion in the United States

- History of religion in the United States

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |