History of religion in the United States facts for kids

Religion in the United States began with the beliefs and practices of Native Americans. Later, religion was also important when some colonies were started. Many early settlers, like the Puritans, came to America to escape religious persecution (being treated unfairly for their beliefs).

Historians discuss how much religion, especially Christianity, influenced the American Revolution. Many of the Founding Fathers were active in their local churches. Some, like Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, had deist ideas, meaning they believed in a creator but thought God didn't directly interfere with the world. Some people call the U.S. a "Protestant nation" because of its strong Protestant roots. Others point out that the nation's founding documents are secular (not religious).

African Americans played a big part in creating their own churches, mostly Baptist or Methodist. Their ministers became important moral and political leaders. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many major church groups started missionary work overseas. Some Protestant groups promoted the "Social Gospel" in the early 1900s, encouraging Americans to improve society. They strongly supported the ban on alcohol. After 1970, older Protestant groups lost members. More conservative groups, like evangelical and fundamentalist churches, grew quickly and influenced politics.

While Protestantism has always been the main religion in the U.S., there was a small but important Catholic population from the start. As the U.S. grew into areas once controlled by Spanish and French empires, the Catholic population increased. Later, many immigrants from Catholic countries in the 1800s and 1900s further increased the number of Catholics. These immigrants also brought many Jewish and Eastern Orthodox people to the U.S. The Catholic Church is the largest single religious group, but all Protestant groups combined are still the largest religious group in the U.S.

Unlike Western Europe, which became less religious in the late 1900s, the U.S. remained very Christian. Religious views on social issues often played a big role in American politics.

Contents

- Understanding Religion in the United States

- Early Religions in America

- Religion Before the American Revolution

- The Puritans and Pilgrims

- Religious Persecution in Early America

- Jewish People Seek Refuge

- The Quakers

- German Settlers in Pennsylvania

- Catholics in Maryland

- Virginia and the Church of England

- Growth of Christianity in the 1700s

- Deism: A Different View of God

- The Great Awakening: A Religious Revival

- Evangelical Growth in the South

- The American Revolution and Religion

- Religion from the Revolution to the Civil War

- Religion During the Civil War

- Religion Since the Civil War

- African-Americans and the Baptist Church

- Religion in the South

- Missions to Native American Reservations

- The Catholic Church in the Late 1800s

- Benevolent and Missionary Societies (1880s–1920s)

- The Social Gospel Movement

- Fundamentalism and Evolution

- Religious Decline Before and During the Great Depression

- World War II and Religion

- Debate: Is America a "Christian Nation"?

- Religious Groups Started in the U.S.

- Eastern Orthodoxy in America

- Judaism in the U.S.

- Church and State Issues

- Islam in the U.S.

Understanding Religion in the United States

Religion in the United States (2019) Protestantism (43%) Catholicism (20%) The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (2%) Unaffiliated (26%) Judaism (2%) Islam (1%) Hinduism (1%) Buddhism (1%) Other religions (3%) Unanswered (2%)

The U.S. government census has never directly asked Americans about their religion. However, it did collect information from different church groups starting in 1945.

Researchers Finke and Stark looked at census data from after 1850. They estimated that in 1776, about 17% of Americans belonged to a specific church. This number grew to 34% by 1850 and 45% by 1890. By 1952, it reached 59%.

How Religious Groups Have Changed (Pew and Gallup Data)

According to the Pew Research Center, the percentage of Protestants in the U.S. has gone down. In 1948, over two-thirds of Americans were Protestant. By 2012, less than half, about 48%, identified as Protestant.

Gallup has asked Americans about their religious preferences every year since 1948. The chart below shows how these percentages have changed over time. Keep in mind that 0% means less than 0.5%.

| Percentage of Americans by religious affiliation (Gallup) |

The decline in Protestant numbers is partly because immigration rules changed after 1965. This allowed more people from non-Protestant countries to come to the U.S. The percentage of Catholics grew until the 1980s, then started to decline. The percentage of Jewish people has gone down from 4% to 2% since 1948, as there has been less Jewish immigration.

The number of people with other religions was very small in 1948 but grew to 5% by 2011. This is partly due to more immigration from non-Christian countries. The percentage of people who are not religious (like atheists or agnostics) has greatly increased from 2% to 13%.

| Religion | 1992 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Baptist | 9% | 10% | 8% | 5% | 4% | 4% |

| Other Baptist | 10% | 9% | 10% | 11% | 13% | 9% |

| Methodist | 10% | 9% | 9% | 8% | 7% | 5% |

| Presbyterian | 5% | 4% | 5% | 3% | 3% | 2% |

| Episcopalian | 2% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 1% |

| Lutheran | 7% | 6% | 7% | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| Pentecostal | 1% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Church of Christ | 2% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 2% | |

| Other Protestant | 11% | 9% | 4% | 5% | 4% | 5% |

| Non-denominational Protestant | 1% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 4% |

| No opinion | 5% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

Over the last 19 years, some older Protestant groups have seen a big drop in their share of the American population. These include Southern Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians. The only Protestant group that grew significantly is non-denominational Protestantism.

Early Religions in America

Native American Beliefs

Native American religions are the spiritual practices of the first peoples of the Americas. These traditional ways are very different from tribe to tribe, based on their unique histories and beliefs. Early European explorers noted that each Native American tribe had its own religious customs.

Their beliefs could involve one God (monotheistic), many gods (polytheistic), or a focus on one main god among others (henotheistic). They also often believed that spirits exist in nature (animistic). Traditional beliefs were usually passed down through oral histories, stories, and teachings within families and communities.

Sometimes, important religious leaders would start revivals. In 1805, Tenskwatawa, known as the Shawnee Prophet, led a religious revival in Indiana. This happened after a smallpox outbreak and a series of witch-hunts. His ideas came from earlier Lenape prophets who predicted a disaster that would destroy European-American settlers. Tenskwatawa told tribes to reject American ways, like giving up firearms and alcohol. He also urged them not to sell any more land to the United States. This revival led to warfare led by his brother Tecumseh against the white settlers.

Native Americans were also the focus of many Christian missionaries. Catholics started missions like the Jesuit Missions amongst the Huron and the Spanish missions in California. Various Protestant groups were also active. By the late 1800s, most Native Americans who joined American society became Christians. Many living on reservations also became Christians. The Navajo, a large and isolated tribe, resisted missionaries until a Pentecostal revival gained their support after 1950.

Religion Before the American Revolution

The New England colonies were settled partly by English people escaping religious persecution. They were founded as "plantations of religion." While some settlers came for other reasons, most left Europe to worship as they believed was right. They supported their leaders' efforts to create a "City upon a Hill" or a "holy experiment." They hoped its success would show that God's plan could work in the American wilderness.

The Puritans and Pilgrims

Puritanism was a movement in England that wanted to reform Protestantism. The first Puritans came to America between 1629 and 1640 and settled in New England, especially the Massachusetts Bay area. They didn't see themselves as completely separate from the English Church. They originally hoped to return and purify England.

Puritans are often confused with Separatists, another Protestant group. Separatists also believed the Church of England was corrupt, but they thought nothing more could be done to purify England. Separatists were persecuted, and their religion was illegal in England. So, they decided to form their own pure church. One group, the Pilgrims, left England for America in 1620. They first settled in Plymouth, Massachusetts. These are the settlers who started the Thanksgiving tradition in America.

Together, the Pilgrims and Puritans helped form the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It's hard to say exactly when Puritanism ended, but most sources agree it declined by the early 1700s. One reason was that people became less committed to their religion.

Puritans valued seriousness, hard work, education, and responsibility. They believed in predestination (God has already decided who will be saved). They did not tolerate anything they considered impure, including Catholicism. Even though they wanted to purify England, they chose their own ministers and church members.

Puritan values might have influenced American ideas like individualism. For example, their idea of "justification-by-faith" focused on the individual's personal values. Their physical break from the Church of England also showed their independence. The Pilgrims also had an influence. When they first arrived, they signed the Mayflower Compact. This document set up a temporary government independent of England, which can be seen as an early step toward the Declaration of Independence.

Religious Persecution in Early America

Even though Puritans were persecuted in Europe, they believed in having one main religion in the state. Once they were in charge in New England, they tried to stop "Schism and vile opinions." A Puritan minister said in 1681 that their goal was not "Toleration." Puritans expelled people who disagreed with them from their colonies. This happened to Roger Williams in 1636 and Anne Hutchinson in 1638. Anne Hutchinson was America's first major female religious leader.

Those who kept returning to Puritan areas, despite being told to leave, risked death. Four Quakers were executed in Boston between 1659 and 1661. Thomas Jefferson noted that Virginia also had anti-Quaker laws, including the death penalty. He believed that if no executions happened there, it wasn't because of more tolerance.

Puritans also started the Salem Witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts. It began with accusations from the local reverend's daughter. More than 200 people were accused of witchcraft, and 20 were executed. The colony later realized the trials were a mistake and tried to help the families of those who were punished.

Founding Rhode Island

In the winter of 1636, Roger Williams was expelled from Massachusetts. He believed in religious freedom. He wrote that "God requireth not an uniformity of Religion to be inacted and enforced in any civill state." Williams later founded Rhode Island based on this idea. He welcomed people of all religious beliefs, even those he disagreed with. He believed that "forced worship stinks in God's nostrils."

Jewish People Seek Refuge

The first record of Jewish people in America shows them arriving on a Dutch ship, the St. Catrina, in 1654. These 23 Jewish refugees were escaping persecution in Dutch Brazil. They arrived in New Amsterdam (which later became New York City). By the next year, this small group had started religious services. Around 1677, a group of Sephardic Jews arrived in Newport, Rhode Island, also seeking religious freedom. By 1678, they had bought land there. Small numbers of Jewish people continued to come to the British North American colonies, mostly settling in port cities. By the late 1700s, Jewish settlers had built several synagogues.

The Quakers

The Religious Society of Friends, also known as Quakers, started in England in 1652 with leader George Fox.

Historians debate if Quakers can be seen as very strict Puritans. Quakers took Puritan ideas like sober behavior to an extreme, glorifying "plainness." They also expanded the Puritan idea of individuals being renewed by the Holy Spirit. Quakers believed in the "Light of Christ" within every person.

Many people at the time thought these teachings were dangerous. Quakers were severely persecuted in England for their different beliefs. By 1680, 10,000 Quakers had been jailed in England, and 243 died in prison.

This persecution led Friends to seek safety in Rhode Island in the 1670s, where they became well-established. In 1681, Quaker leader William Penn received land in Pennsylvania from Charles II of England. Many more Quakers came to Pennsylvania from England, Wales, and Ireland by 1685. They wanted to worship freely. While Quakers shared some beliefs with Puritans, they disagreed on forcing everyone to follow one religion.

German Settlers in Pennsylvania

During the mid-1700s, many Germans moved to Pennsylvania. Most were Lutherans, Reformed, or members of smaller groups like Mennonites, Amish, Dunkers, Moravians, and Schwenkfelders. Most of them became farmers.

William Penn, a Quaker, owned the colony. His agents encouraged German immigration by promoting Pennsylvania's economic benefits and religious freedom. The arrival of so many religious groups made Pennsylvania seem like a "safe place for banished sects."

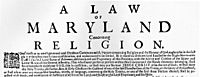

Catholics in Maryland

For their political opposition, Catholics were often harassed and lost many civil rights after the reign of Elizabeth I. George Calvert wanted to find a safe place for his Catholic friends. In 1632, he got a charter from Charles I for the land between Pennsylvania and Virginia. This Maryland charter didn't set religious rules, but it was understood that Catholics would not be persecuted. His son, Lord Baltimore, was a Catholic who inherited the grant. In 1634, his ships, the Ark and the Dove, sailed with the first 200 settlers to Maryland, including two Catholic priests. Lord Baltimore believed religion was a private matter. He didn't want an official church and promised religious freedom to all Christians.

The situation for Catholics in Maryland changed throughout the 1600s as they became a smaller part of the population. After the Glorious Revolution of 1689 in England, the Church of England became the official church in the colony. English laws that took away Catholics' right to vote, hold office, or worship publicly were enforced. Maryland's first state constitution in 1776 brought back religious freedom. Maryland remained an important center for Catholics. However, at the time of the American Revolution, Catholics made up less than one percent of the white population in the thirteen states.

Virginia and the Church of England

Virginia was the largest and most important colony. The Church of England was the official church there. The bishop of London, who oversaw Anglican churches in the colonies, made Virginia a special target for missionaries. By 1624, 22 clergymen had been sent there. Being the official church meant that local taxes went to the local parish. This money was used for local government needs like roads and helping the poor, as well as paying the minister's salary. There was never a bishop in colonial Virginia. Local church leaders, called vestrymen, were laymen (not clergy) who controlled the parish and managed local taxes and aid.

When the elected assembly, the House of Burgesses, was created in 1619, it passed religious laws that strongly favored Anglicanism. In 1632, a law required "uniformity throughout this colony" with the Church of England.

Ministers often complained that colonists were not interested during church services. Because there were few towns, churches had to serve scattered settlements. There was also a shortage of trained ministers, making it hard to practice faith outside the home. Some ministers encouraged people to be religious at home, using the Book of Common Prayer for private worship. This allowed devout Anglicans to have a strong religious life even if church services were not satisfying. However, this focus on personal devotion reduced the need for a bishop or a large church system. This opened the way for the First Great Awakening, which drew people away from the official church.

Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and other evangelical groups challenged what they saw as immoral behavior. They created a male leadership role that followed Christian principles and became very influential in the 1800s. These groups funded their own ministers and wanted the Anglican church to lose its official status. These dissenting groups grew much faster than the official church, making religious differences important in Virginia politics leading up to the Revolution. The Patriots, led by Thomas Jefferson, ended the official status of the Anglican Church in 1786.

Growth of Christianity in the 1700s

Many scholars used to think that Americans in the 1700s were less religious than the first settlers. However, new research shows a high level of religious activity in the colonies after 1700. One expert says that Judeo-Christian faith was "rising" rather than declining. Another sees "rising vitality in religious life" from 1700 onward. Church attendance and the building of new churches support these ideas. Between 1700 and 1740, about 75–80% of the population attended churches, which were being built very quickly.

By 1780, between 10% and 30% of adult colonists belonged to a church, not counting enslaved people or Native Americans. North Carolina had the lowest percentage (about 4%), while New Hampshire and South Carolina had the highest (about 16%).

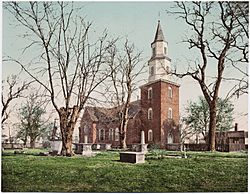

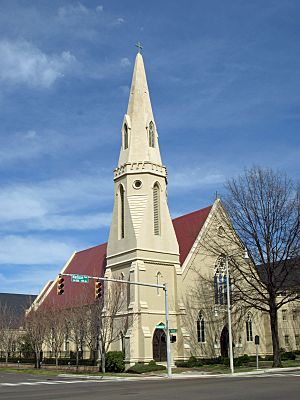

Church buildings in 18th-century America varied greatly. They ranged from simple buildings in new rural areas to fancy ones in wealthy cities along the East Coast. Churches reflected the customs, traditions, wealth, and social status of the groups that built them. German churches, for example, had features not found in English ones.

Deism: A Different View of God

Deism is a philosophical and religious idea that suggests God created the world but does not directly interfere with it. These ideas became popular in America in the late 1700s. Deism at that time "accepted a creator based on reason but rejected a supernatural God who interacts with people." A type of deism called Christian deism focused on morality. It rejected the traditional Christian belief in the divinity of Christ, often seeing him as a great human teacher of morals. The most famous Deist was Thomas Paine, but many other founders used Deist language in their writings.

The Great Awakening: A Religious Revival

The First Great Awakening was a wave of strong religious feeling among Protestants in the American colonies during the 1730s and 1740s. It had a lasting impact on American Christianity. Preaching deeply affected listeners, making them feel personal guilt and a sense of salvation through Christ. The Great Awakening moved away from rituals and ceremonies, making the relationship with God very personal for ordinary people. Historians see it as part of a larger Protestant movement that also led to Pietism in Germany and Methodism in England. It brought Christianity to enslaved people and challenged existing church authority in New England. It caused a split between new revivalists and older traditionalists who focused on rituals and doctrine.

The new style of sermons and how people practiced their faith changed Christianity in America. People became emotionally involved in their relationship with God, rather than just listening to intellectual talks. Ministers who used this new style were called "new lights," while others were "old lights." People started studying the Bible at home. This meant that religious information was no longer controlled only by the church, similar to individualistic trends during the Protestant Reformation in Europe.

The main idea of evangelicalism is that individuals can change from a state of sin to a "new birth" through Bible preaching, leading to faith. The First Great Awakening led to changes in American colonial society. In New England, it was important among many Congregationalists. In the Middle and Southern colonies, especially in rural areas, it influenced Presbyterians. In the South, Baptist and Methodist preachers converted both white people and enslaved Black people.

In the early 1700s, a series of local "awakenings" began in the Congregational church in the Connecticut River Valley. Ministers like Jonathan Edwards were involved. By the 1730s, these spread into what was seen as a general outpouring of the Spirit across the American colonies, England, Wales, and Scotland.

In large outdoor revival meetings, preachers like George Whitefield led thousands of people to a "new birth." The Great Awakening, which ended in New England by the mid-1740s, split the Congregational and Presbyterian churches into supporters ("New Lights" and "New Side") and opponents ("Old Lights" and "Old Side"). Many New England New Lights became Separate Baptists. Through the efforts of a charismatic preacher named Shubal Stearns, and similar to the New Side Presbyterians, they brought the Great Awakening to the southern colonies. This started a series of revivals that lasted into the 1800s.

The groups that supported the Awakening and its evangelical focus—Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists—became the largest American Protestant denominations by the early 1800s. Groups that opposed or were split by the Awakening—Anglicans, Quakers, and Congregationalists—fell behind.

Unlike the Second Great Awakening that began around 1800, which reached out to people who didn't go to church, the First Great Awakening focused on people who were already church members. It changed their rituals, their devotion, and how they saw themselves.

Evangelical Growth in the South

The South was originally settled and controlled by Anglicans. They were the dominant religion among wealthy plantation owners. However, their formal, ritualistic church had little appeal to ordinary people, both white and Black.

Baptist Influence

By the 1760s, Baptist churches began attracting Southerners, especially poor white farmers. This was due to many traveling missionaries. They offered a new, more democratic religion. They welcomed enslaved people to their services, and many became Baptists. Baptist services focused on emotion. The only ritual, baptism, involved fully immersing adults (not sprinkling, like in the Anglican tradition). Baptists enforced rules against wasteful spending, missing services, cursing, and excessive partying. Church trials were common, and members who didn't follow the rules were expelled.

Historians have discussed how these religious rivalries affected the American Revolution (1765–1783). Baptist farmers brought a new idea of equality that largely replaced the more aristocratic ideas of Anglican planters. However, both groups supported the Revolution. There was a big difference between the simple lives of Baptists and the wealth of Anglican planters, who controlled local government. Baptist church rules, which the wealthy sometimes mistook for radicalism, actually helped keep order. The fight for religious tolerance happened during the American Revolution, as Baptists worked to end the Anglican church's official status.

Baptists, German Lutherans, and Presbyterians funded their own ministers. They supported ending the Anglican church's official status.

Methodist Missionaries

Methodist missionaries were also active in the late colonial period. From 1776 to 1815, Methodist Bishop Francis Asbury traveled extensively to visit Methodist congregations in western areas. In the 1780s, traveling Methodist preachers carried anti-slavery petitions. They called for an end to slavery. However, counter-petitions were also circulated. These petitions were debated in the Assembly, but no laws were passed. After 1800, there was less religious opposition to slavery.

The American Revolution and Religion

The Revolution caused some religious groups to split, especially the Church of England. Its clergy had sworn loyalty to the king. Quakers, who were traditionally pacifist (opposed to war), also faced challenges. Religious practice decreased in some places due to absent ministers and damaged churches.

The Church of England During the Revolution

The American Revolution deeply affected the Church of England in America. This was because the English monarch was the head of the church. Church of England priests, when they became ministers, swore loyalty to the British crown.

The Book of Common Prayer included prayers for the monarch, asking God to protect him and give him victory over his enemies. In 1776, these "enemies" were American soldiers, who were also friends and neighbors of American Church of England members. Being loyal to the church and its head could be seen as treason to the American cause.

Patriotic American members of the Church of England didn't want to give up their faith. So, they changed The Book of Common Prayer to fit the new political situation. After the Treaty of Paris (1783), which officially recognized American independence, Anglicans were left without leaders or a formal organization. Samuel Seabury became a bishop through the Scottish Episcopal Church in 1784. He lived in New York. After a requirement to swear loyalty to the Crown was removed, two Americans became bishops in London in 1786 for Virginia and Pennsylvania. The Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States was created in 1787. It became an independent church that was still connected to the Church of England.

Religion from the Revolution to the Civil War

Historians have recently discussed how religious Americans were in the early 1800s. They look at secularism (non-religious views), deism, old religious practices, and new evangelical forms from the Great Awakening.

The U.S. Constitution and Religion

The Constitution was approved in 1788. It only mentions religion in Article Six. This article says that "No religious test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States." This means you don't have to belong to a certain religion to hold a federal job. Most colonies had such tests, and some states kept them for a short time. The Fourteenth Amendment later applied this rule to the states.

However, the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, added in 1791, is very important. It defines how the federal government relates to religious freedom and prevents an official church from being established. It says, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” These two parts are called the "establishment clause" and the "free exercise clause." They are the basis for the Supreme Court's idea of "separation of church and state." On August 15, 1789, James Madison explained that Congress should not create an official religion or force people to worship in any way against their conscience. All states ended official state religions by 1833; Massachusetts was the last. This stopped the practice of using taxes to support churches.

The Treaty of Tripoli

The Treaty of Tripoli was an agreement between the U.S. and Tripolitania. President John Adams sent it to the Senate, which approved it on June 7, 1797. It became law on June 10, 1797. This treaty was a normal diplomatic agreement. However, it gained attention later because the English version included a clause about religion in the United States:

As the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion,—as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility, of Mussulmen [Muslims],—and as the said States never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan [Mohammedan] nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

Franklin T. Lambert, a history professor, says that by their actions, the Founding Fathers made it clear that their main concern was religious freedom. He notes that ten years after the Constitution was written, the country told the world that the United States was a secular (non-religious) state.

Despite this clear separation of government and religion, the nation's culture and society became strongly Christian. In an 1892 court case, Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court stated that America was "a Christian nation."

The Great Awakenings and Evangelicalism

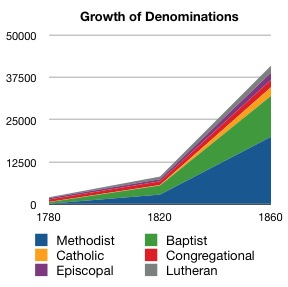

The "Great Awakenings" were large religious revivals that happened in waves. They moved many people from not attending church to becoming active church members. The Methodists and Baptists were most active in organizing these revivals. The number of Methodist church members grew from 58,000 in 1790 to 1,661,000 in 1860. In 70 years, Methodist membership grew almost 29 times, while the total U.S. population grew 8 times.

These awakenings made evangelicalism a very powerful force in American religion. Historian Randall Balmer explains that evangelicalism is a North American phenomenon. It came from a mix of Pietism, Presbyterianism, and Puritanism. Evangelicalism took characteristics from each, like warm spirituality from Pietists and focus on individuals from Puritans.

The Second Great Awakening

In 1800, major revivals began across the nation: the Second Great Awakening in New England and the Great Revival in Cane Ridge, Kentucky. A key new idea from the Kentucky revivals was the camp meeting.

These revivals were first organized by Presbyterian ministers. They were like the long outdoor communion events used by the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, which often led to emotional displays of faith. In Kentucky, pioneers would load their families and supplies into wagons and drive to Presbyterian meetings. They would set up tents and stay for several days.

When people gathered in a field or forest for a long religious meeting, the site became a camp meeting. The religious revivals at Kentucky camp meetings were so intense and emotional that their original sponsors, the Presbyterians and Baptists, soon stopped supporting them. However, the Methodists adopted and used camp meetings. They brought them to the eastern states, where for decades they were a key part of the Methodist church.

The Second Great Awakening (1800–1830s), unlike the first, focused on people who didn't go to church. It tried to give them a sense of personal salvation through revival meetings. This revival quickly spread through Kentucky, Tennessee, and southern Ohio. Each church group had strengths that helped it grow on the frontier. For example, Methodists had an efficient system using ministers called circuit riders. These riders found people in remote frontier areas. Circuit riders came from ordinary people, which helped them connect with the frontier families they wanted to convert.

The Second Great Awakening had a huge impact on American religious history. By 1859, evangelicalism became a kind of national church or religion. The Methodists, who were very organized, made the biggest gains. Francis Asbury (1745–1816) led the American Methodist movement and became one of the most important religious leaders of the young country. Traveling across the eastern U.S., Methodism grew quickly under Asbury's leadership to become the nation's largest and most widespread church group. The number of Baptists and Methodists grew much more than older groups like Anglicans, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists. Efforts to apply Christian teachings to solve social problems foreshadowed the Social Gospel movement of the late 1800s. It also led to the start of groups like The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Restoration Movement, and the Holiness movement.

The Third Great Awakening

The Third Great Awakening was a time of religious activity in American history from the late 1850s to the early 1900s. It affected Protestant groups and had a strong focus on social activism. It gained strength from the idea that the Second Coming of Christ would happen after humanity had improved the whole world. The Social Gospel Movement and the worldwide missionary movement grew from this Awakening. New groups like the Holiness movement, Nazarene movements, and Christian Science also appeared.

The main Protestant churches grew rapidly in numbers, wealth, and education. They moved away from their frontier beginnings and became centered in towns and cities. Thinkers like Josiah Strong promoted a strong Christianity that reached out to non-churchgoers in America and worldwide. Others built colleges and universities to train future leaders. Each church group supported active missionary societies, making the role of missionary very respected. Most of these Protestants (in the North) supported the Republican Party. They urged it to support the ban on alcohol and other social reforms.

The awakening in many cities in 1858 was interrupted by the American Civil War. In the South, however, the Civil War encouraged revivals and strengthened the Baptists. After the war, Dwight L. Moody made revivals a key part of his work in Chicago by founding the Moody Bible Institute. The hymns of Ira Sankey were especially influential.

The wealthy class of the Gilded Age faced strong criticism from Social Gospel preachers and reformers during the Progressive Era. These reformers worked on issues like child labor, mandatory elementary education, and protecting women from exploitation in factories.

All major church groups supported growing missionary activities both within the United States and around the world.

Colleges connected to churches quickly grew in number, size, and quality. "Muscular Christianity" became popular among young men on college campuses and in city YMCAs. It was also popular in church youth groups like the Epworth League for Methodists.

Benevolent and Missionary Societies

Benevolent societies were new in America during the first half of the 1800s. They first aimed to convert non-believers. Eventually, they focused on fixing all kinds of social problems. These societies were a direct result of the energy from the evangelical movement. Presbyterian evangelist Charles Grandison Finney said that "the evidence of God's grace" was how benevolent a person was toward others.

The evangelical establishment used this strong network of volunteer, inter-church benevolent societies to make the nation more Christian. The earliest and most important of these groups focused on converting non-believers or creating conditions (like sobriety, sought by temperance societies) where conversions could happen. The six largest societies in 1826–27 were: the American Education Society, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, the American Bible Society, the American Sunday School Union, the American Tract Society, and the American Home Missionary Society.

Most church groups ran missions abroad. They also had missions for Native Americans and Asians in the U.S. Historian Hutchinson says that the American desire to reform the world was greatly boosted by the passion of evangelical Christians. Grimshaw argues that women missionaries were very enthusiastic about missionary work. They contributed "substantially to the religious conversion and reorientation of Hawaiian culture in the first half of the 19th century."

Rise of African American Churches

Scholars disagree on how much African culture influenced Black Christianity in 18th-century America. However, it's clear that Black Christianity was based on evangelicalism.

The Second Great Awakening is called the "central and defining event in the development of Afro-Christianity." During these revivals, Baptists and Methodists converted many Black people. However, many Black converts were unhappy with how they were treated by white church members. They were also disappointed that many white Baptists and Methodists, who had supported ending slavery after the American Revolution, were now less committed to it.

When their unhappiness grew too strong, some Black leaders formed new church groups. In 1787, Richard Allen and his friends in Philadelphia left the Methodist Church. In 1815, they founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. This church, along with independent Black Baptist congregations, grew quickly throughout the 1800s. By 1846, the AME Church, which started with eight clergy and five churches, had grown to 176 clergy, 296 churches, and 17,375 members.

Religion During the Civil War

Religion in the Union (North)

Protestant religion was very strong in the North in the 1860s. Protestant groups took different stances on the war. Generally, evangelical groups like the Methodists, Northern Baptists, and Congregationalists strongly supported the war effort. More traditional groups like Catholics, Episcopalians, Lutherans, and conservative Presbyterians usually avoided discussing the war to prevent dividing their members. Some clergy who supported the Confederacy were called Copperheads, especially in border areas.

Churches worked to support their soldiers and their families at home. Much of the political talk at the time had a strong religious tone. The United States Christian Commission, which included different Protestant groups, sent agents to Army camps. They provided emotional support, books, newspapers, food, and clothing. Through prayer, sermons, and welfare work, the agents helped soldiers' spiritual and physical needs. They tried to encourage the men to live a Christian life.

No church group was more active in supporting the Union than the Methodist Episcopal Church. Historian Richard Carwardine says that for many Methodists, Lincoln's victory in 1860 meant the arrival of God's kingdom in America. They were motivated by a vision of freedom for enslaved people, freedom for abolitionists, and a new direction for the Union. Methodists strongly supported the Radical Republicans and their tough stance toward the white South. Dissident Methodists left the church. During Reconstruction, Methodists helped form Methodist churches for freed slaves. They also moved into Southern cities, sometimes taking control of buildings that belonged to the Southern branch of the church, with help from the Army. The Methodist magazine Ladies' Repository promoted Christian family activism. Its articles offered moral uplift to women and children. It presented the War as a great moral fight against a corrupt Southern society. It suggested activities families could do to help the Union cause.

Religion in the Confederacy (South)

The Confederate States of America (CSA) was overwhelmingly Protestant. Religious revivals were common during the war, especially in Army camps. Both free and enslaved people identified with evangelical Protestantism. Freedom of religion and separation of church and state were fully protected by Confederate laws. Church attendance was very high, and chaplains played a major role in the Army.

The issue of slavery had already split evangelical denominations by 1860. During the war, Presbyterians and Episcopalians also split. Catholics did not split. Baptists and Methodists together made up the majority of both white and enslaved populations. Wealthy white Southerners mostly belonged to the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, which reluctantly separated from the Episcopal Church (USA) in 1861. Other wealthy Southerners were Presbyterians who joined the Presbyterian Church in the United States, which split off in 1861. Joseph Ruggles Wilson (President Woodrow Wilson's father) was a prominent leader. Catholics included Irish working-class people in port cities and old French families in southern Louisiana.

Religion Since the Civil War

Historian Sidney Mead says that organized religion faced two big challenges in the late 1800s: one to its social programs and another to its ideas. Changing social conditions forced a shift from the "gospel of wealth" to the Social Gospel. The "gospel of wealth" encouraged rich Christians to share their money through charity. The Social Gospel called on ministers to lead efforts to eliminate social problems. The second challenge came from modern science, especially Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. This led to different religious responses, including strict interpretations of the Bible, liberal views, and scientific modernism. Protestantism slowly moved away from focusing only on individual salvation. However, fundamentalists resisted this trend, trying to hold onto the core ideas of Christianity.

The nation also saw new minority religions emerge. According to historian R. Laurence Moore, Christian Scientists, Pentecostals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Catholics felt like outsiders who were being persecuted. This made them hold tightly to their rights as full citizens.

African-Americans and the Baptist Church

After the Civil War, Black Baptists wanted to practice Christianity without racial discrimination. They quickly set up several separate state Baptist conventions. In 1866, Black Baptists from the South and West formed the Consolidated American Baptist Convention. This Convention eventually ended, but three national conventions formed in its place. In 1895, these three merged to create the National Baptist Convention. It is now the largest African-American religious organization in the United States. White-majority denominations ran many missions for Black people, especially in the South. Even before the Civil War, Catholics had established churches for Black people in Louisiana, Maryland, and Kentucky.

Religion in the South

Historian Edward Ayers describes the South as a poor region with a rich spiritual life:

- Religious faith and language were everywhere in the New South. It was in public speeches and private feelings. For many, religion guided politics, powered laws and reforms, and inspired help for the poor. People saw everything from dating to raising children to death in religious terms. Even those with doubts couldn't escape the images and power of faith.

Baptists were the largest group for both Black and white people, with many small rural churches. Methodists were second largest for both races, with a more organized structure. Smaller fundamentalist groups that grew very large in the 1900s were starting to appear. Groups of Roman Catholics lived in the region's few cities and southern Louisiana. Wealthy white Southerners were mostly Episcopalians or Presbyterians. Across the region, ministers held respected positions, especially in the Black community where they were often political leaders. When most Black people lost the right to vote after 1890, Black preachers were still allowed to vote. Revivals happened regularly, attracting large crowds. Usually, those who already believed attended, so the number of new converts was small. But everyone enjoyed the preaching and socializing. No alcohol was served, as the main social reform promoted by Southerners was the ban on alcohol. This was also the main way women activists could get involved politically, as the women's right to vote movement was weak.

Missions to Native American Reservations

Starting in the colonial era, most Protestant groups ran missions for Native Americans. After the Civil War, these programs expanded. Major Western reservations were placed under the control of religious groups. This was largely to avoid financial problems and bad relationships that had happened before. In 1869, Congress created the Board of Indian Commissioners. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed volunteers who were "intelligent and generous." The Grant Board had wide power to oversee the Bureau of Indian Affairs and "civilize" Native Americans. Grant decided to divide Native American appointments "among the religious churches." By 1872, 73 Indian agencies were divided among religious groups. A key policy was to put western reservations under the control of religious groups. In 1872, Methodists received 14 reservations, Orthodox Quakers ten, Presbyterians nine, Episcopalians eight, Catholics seven, and so on. The selection rules were unclear, and critics said the Peace Policy violated Native American religious freedom. Catholics wanted a bigger role and set up the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions in 1874. The Peace Policy lasted until 1881. Historian Cary Collins says Grant's Peace Policy failed in the Pacific Northwest mainly because of competition between religious groups and their focus on converting people.

The Catholic Church in the Late 1800s

The main reason for the large number of Catholics in the United States was the huge waves of European immigrants in the 1800s and 1900s. These immigrants came especially from Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Poland. More recently, most Catholic immigrants come from Latin America, particularly Mexico.

Irish immigrants came to lead the church, providing most of the bishops, college presidents, and lay leaders. They strongly supported the "ultramontane" position, which favored the Pope's authority.

In the late 1800s, the church tried to standardize its rules by holding the Plenary Councils of Baltimore. These councils led to the Baltimore Catechism and the creation of The Catholic University of America.

In the 1960s, the church underwent big changes, especially in its worship services. It started using the language of the people instead of Latin. The number of priests and nuns dropped sharply as fewer people joined and many left their religious roles.

Benevolent and Missionary Societies (1880s–1920s)

By 1890, American Protestant churches supported about 1,000 overseas missionaries and their wives. Women's organizations in local churches were very active in getting volunteers and raising money. Inspired by the Social Gospel movement, young people on college campuses and in city centers like the YMCA helped increase the total number of missionaries to 5,000 by 1900. From 1886 to 1926, the most active group for recruiting was the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions (SVM). It used YMCA groups on campuses to encourage over 8,000 young Protestants to join. This idea was quickly copied by the World's Student Christian Federation (WSCF), which was strong in Great Britain, Europe, Australia, India, China, and Japan. At first, training focused on understanding the Bible. Later, it was realized that effective missionaries needed to understand the local language and culture. Important leaders included John Mott (head of the YMCA) and Robert E. Speer (a chief Presbyterian organizer).

With much attention on the anti-Western Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), American Protestants made missions to China a high priority. They supported 500 missionaries in 1890, over 2,000 in 1914, and 8,300 in 1920. By 1927, they had opened 16 universities, six medical schools, and four theology schools in China. They also opened 265 middle schools and many elementary schools. The number of converts was not large, but the educational influence was huge and long-lasting.

The Social Gospel Movement

A powerful influence in northern Protestant churches was the Social Gospel, especially from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. Its goal was to apply Christian ethics to social problems. This included issues like economic inequality, poverty, crime, racial tensions, slums, pollution, child labor, lack of unions, poor schools, and the dangers of war. Theologically, Social Gospel supporters wanted to see the Lord's Prayer come true: "Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven." They generally believed that the Second Coming of Christ could not happen until humanity got rid of social problems through human effort. Social Gospel thinkers rejected the idea that Christ's Second Coming was about to happen and that Christians should only prepare for it. This latter view was strongest among fundamentalists and in the South. The Social Gospel was more popular among clergy than among regular church members. Its leaders were mostly connected to the liberal part of the progressive movement and were generally theologically liberal. Important leaders included Richard T. Ely and Walter Rauschenbusch. Many politicians were influenced by it, notably William Jennings Bryan and Woodrow Wilson. The most debated Social Gospel reform was the ban on alcohol. This was very popular in rural areas, including the South, but unpopular in larger cities where mainline Protestantism was weaker among voters.

Fundamentalism and Evolution

In the 1920s, some "strident fundamentalists" fought against the teaching of evolution in schools and colleges. They tried to pass state laws affecting public schools. William Bell Riley took the lead in the 1925 Scopes Trial. He brought in famous politician William Jennings Bryan to help the local prosecutor. Bryan's involvement brought national media attention to the trial. For 50 years after the Scopes Trial, fundamentalists had little success in shaping government policy. They were generally defeated in their efforts to change the mainline denominations, which refused to join fundamentalist attacks on evolution. Especially after the Scopes Trial, liberals saw a division between Christians who supported teaching evolution (viewed positively) and those who opposed it (viewed negatively).

Webb (1991) describes the political and legal battles between strict creationists and Darwinists. They fought over how much evolution would be taught as science in Arizona and California schools. After Scopes was convicted, creationists across the U.S. sought similar anti-evolution laws for their states. They wanted to ban evolution as a topic or at least make it an unproven theory taught alongside the biblical creation story. Educators, scientists, and other respected people favored evolution. This struggle happened later in the Southwest than in other U.S. areas and continued through the Sputnik era.

Religious Decline Before and During the Great Depression

Robert T. Handy points to a religious decline in the United States starting around 1925. This worsened during the economic depression that began in 1929. When Protestantism became too closely linked with American culture, its religious messages were weakened. Fundamentalist churches grew too fast and had financial problems. Mainstream churches were well-funded in the late 1920s. However, they lost confidence in whether their social gospel was needed in a time of prosperity, especially since the ban on alcohol failed.

Regarding their international missions, mainstream churches realized that missions were successful in opening modern schools and hospitals but failed in converting people. The leading theorist Daniel Fleming stated that the new areas for Christian outreach were not Africa and Asia, but rather materialism, racial injustice, war, and poverty. The number of missionaries from mainstream denominations began to drop sharply. In contrast, evangelical and fundamentalist churches, which never fully supported the social gospel, increased their efforts worldwide, focusing on conversion. At home, mainstream churches had to expand their charity roles from 1929–31. But they collapsed financially due to the huge economic disaster for ordinary Americans. Suddenly, in 1932–33, mainline churches lost one of their historical roles of giving aid to the poor. The national government took over this role without any religious aspect. Handy argues that the deep self-doubt meant the usual religious revivals during economic depressions were absent in the 1930s. He concludes that the Great Depression marked the end of Protestantism's dominance in American life.

World War II and Religion

In the 1930s, pacifism (opposition to war) was very strong in most Protestant churches. Only a few religious leaders, like Reinhold Niebuhr, paid serious attention to the threats from Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, or militaristic Japan. After Pearl Harbor in December 1941, almost all religious groups supported the war effort. They provided chaplains, for example. Pacifist churches, like the Quakers and Mennonites, were small but maintained their opposition to military service. Many young members, like Richard Nixon, voluntarily joined the military. Unlike in 1917–1918, the government generally respected these positions. It set up non-combat civilian roles for conscientious objectors.

Typically, church members sent their sons to the military without protest. They accepted shortages and rationing as necessary for the war. They bought war bonds, worked in munitions factories, and prayed intensely for safe returns and victory. Church leaders, however, were more cautious. They held onto ideals of peace, justice, and humanitarianism. Sometimes, they criticized military policies like bombing enemy cities. They sponsored 10,000 military chaplains and set up special ministries near military bases. These focused not only on soldiers but also on their young wives who often followed them. Mainstream Protestant churches supported the "Double V campaign" of Black churches. This campaign aimed for victory against enemies abroad and victory against racism at home. However, there was little religious protest against the imprisonment of Japanese Americans on the West Coast or against segregation of Black people in the services. The strong moral outrage about the Holocaust mostly appeared after the war ended, especially after 1960. Many church leaders supported studies of postwar peace plans, like those by John Foster Dulles, a leading Protestant layman. Churches promoted strong support for European relief programs, especially through the United Nations. In one of the largest white Protestant groups, the Southern Baptists, there was a new awareness of international affairs. They had a very negative reaction to the Axis dictatorships. They also had a growing fear of the Catholic Church's power in American society. The military brought strangers together who found a common American identity, leading to a sharp decrease in anti-Catholic feelings among veterans. In the general population, public opinion polls show that religious and ethnic prejudice were less common after 1945. However, some anti-Catholic bias, anti-Semitism, and other discrimination continued.

Debate: Is America a "Christian Nation"?

Since the late 1800s, some right-wing Christians have argued that the United States is fundamentally Christian in its origins. They promote American exceptionalism (the idea that the U.S. is unique). They oppose liberal scholars and emphasize the Christian identity of many Founding Fathers. Critics argue that many of these Christian founders actually supported the separation of church and state. They would not support the idea that they were trying to found a Christian nation.

In Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, an 1892 Supreme Court decision, Justice David Josiah Brewer wrote that America was "a Christian nation." He later wrote and lectured widely on this topic. He stressed that "Christian nation" was an informal description, not a legal rule. He said that in American life, "as expressed by its laws, its business, its customs, and its society, we find everywhere a clear recognition of the same truth… this is a religious nation."

Religious Groups Started in the U.S.

Restorationism: Bringing Back Early Christianity

Restorationism is the belief that a purer form of Christianity should be brought back, using the early church as a model. Many restorationist groups believed that modern Christianity had strayed from the true, original Christianity. They tried to "reconstruct" it, often using the Book of Acts as a guide. Restorationists usually don't see themselves as "reforming" a church that has always existed since Jesus's time. Instead, they believe they are restoring the Church that they think was lost at some point. "Restorationism" often refers to the Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement. The term is also used to describe the Latter-day Saints and the Jehovah's Witness Movement.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Another unique religious group, the Latter Day Saint movement (also known as Mormons), started in the early 1800s. It appeared in a very religious area of western New York called the burned-over district. This area had seen many revivals. Joseph Smith said he had visions and messages from God and angels. These gave him instructions as a prophet and a restorer of the original teachings of early Christianity. After publishing the Book of Mormon (which he said he translated from ancient American prophets' records on golden plates), Smith organized The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1830. He set up a theocracy (a government ruled by religious leaders) in Nauvoo, Illinois. He even ran for president in 1844.

Latter-Day Saints' beliefs in theocracy and polygamy (having more than one spouse) caused many people to dislike them. Anti-Mormon propaganda and violent attacks were common. The Latter-Day Saints were forced out of state after state. Smith was killed in 1844. Brigham Young then led the Latter Day Saints Exodus from the United States to Mexican territory in Utah in 1847. They settled the Latter DAy Saint Corridor. The United States gained control of this area in 1848. It rejected the Latter-Day Saints' 1849 plan for self-governance. Instead, it created the Utah Territory in 1850. Conflicts between Latter-Day Saints and federal officials led to the small Utah War of 1857–1858. After this, Utah remained occupied by Federal troops until 1861.

Congress passed the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act of 1862 to stop the Latter-Day Saints' practice of polygamy. However, President Abraham Lincoln did not enforce this law. Instead, Lincoln quietly allowed Brigham Young to ignore the act in exchange for not getting involved in the American Civil War.

After the war, efforts to enforce polygamy restrictions were limited until the 1882 Edmunds Act. This law made it easier to prosecute unlawful cohabitation. It also took away polygamists' right to vote, serve on juries, and hold political office. The later 1887 Edmunds–Tucker Act officially ended the LDS Church's legal status and took away church property. It also required an anti-polygamy oath for voters, jurors, and public officials. It made civil marriage licenses mandatory, prevented spouses from testifying in polygamy cases, took away women's voting rights, replaced local judges with federal ones, and removed local control of schools. After a 1890 Supreme Court ruling found the Edmunds–Tucker Act constitutional, and with most church leaders hiding or imprisoned, the church issued the 1890 Manifesto. This advised church members against entering legally forbidden marriages. Those who disagreed moved to Canada or Latter Day Saints colonies in Mexico, or hid in remote areas. With the polygamy issue resolved, church leaders were pardoned or had their sentences reduced. Property was returned to the church, and Utah eventually became a state in 1896.

Thanks to worldwide missionary work, the church grew from 7.7 million members worldwide in 1989 to 14 million in 2010.

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses are a fast-growing religious group that remains separate from other Christian denominations. It began in 1872 with Charles Taze Russell. However, it had a major split in 1917 when Joseph Franklin Rutherford became its president. Rutherford gave the movement new direction and renamed it "Jehovah's Witnesses" in 1931. From 1925 to 1933, many important changes were made to their beliefs. Attendance at their yearly Memorial dropped from 90,434 in 1925 to 63,146 in 1935. Since 1950, their growth has been very rapid.

During World War II, Jehovah's Witnesses faced mob attacks in America. They were temporarily banned in Canada and Australia because they did not support the war effort. They won important Supreme Court cases about free speech and religion. These cases had a big impact on how these rights are understood for everyone. In 1943, the United States Supreme Court ruled in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette that school children who were Jehovah's Witnesses could not be forced to salute the flag.

Christian Science

The Church of Christ, Scientist was founded in 1879 in Boston by Mary Baker Eddy. She wrote its main book, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, which offers a unique way of understanding Christian faith. Christian Science teaches that the reality of God means that sin, sickness, death, and the material world are not real. Stories of miraculous healing are common in the church, and followers often refuse traditional medical treatments. Sometimes, legal problems arise when they forbid medical treatment for their children.

This Church is unique among American religious groups in several ways. It is very centralized, with all local churches being branches of the main church in Boston. There are no ministers, but there are practitioners who are important to the movement. These practitioners run local businesses that help members heal their illnesses through the power of the mind. They rely on the Church's approval for their clients. Starting in the late 1800s, the Church quickly lost members, although it does not publish statistics. Its main newspaper, Christian Science Monitor, lost most of its subscribers and stopped its paper version to become an online source.

Other Religious Groups Founded in the U.S.

- Adventism - started as a movement among different Christian groups. Its most famous leader was William Miller. In the 1830s in New York, he became convinced that Jesus's Second Coming was very near.

- Churches of Christ/Disciples of Christ - a restoration movement with no central governing body. The Restoration Movement became a clear historical event in 1832. This is when restorationists from two major movements, led by Barton W. Stone and Alexander Campbell, merged.

- Episcopal Church - founded as a branch of the Church of England. It is now the U.S. branch of the Anglican Communion.

- National Baptist Convention - the largest African American religious organization in the United States. It is also the second largest Baptist group in the world.

- Pentecostalism - a movement that emphasizes the role of the Holy Spirit. Its historical roots are in the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles, California, from 1904 to 1906, started by Charles Parham.

- Reconstructionist Judaism

- Southern Baptist Convention - the largest Baptist group in the world and the largest Protestant denomination in the United States. In 1995, it apologized for its 1845 origins in defending slavery and racial superiority.

- Unitarian Universalism - a liberal religious movement founded in 1961. It formed from the joining of the well-established Unitarian and Universalist churches.

- United Church of Christ - formed in 1957 as a "united and uniting" church. It was a merger of the Congregational Christian Church and Evangelical and Reformed Church. Its congregations came from Congregationalist churches of New England, German Lutheran and Reformed Churches, and various "Christian" churches.

- Cumberland Presbyterian Church - founded in 1810 in Dickson County, Tennessee. It was started by Samuel McAdow, Finis Ewing, and Samuel King.

Eastern Orthodoxy in America

Eastern Orthodoxy came to North America when Russian America (Alaska) was founded in the 1740s. After Russia sold Alaska in 1867, some missionaries stayed.

In the 21st century, Eastern Orthodox Christianity has many followers, religious communities, and organizations. Most members are Russian Americans, Turkish Americans, Greek Americans, Arab Americans, Ukrainian Americans, Albanian Americans, Macedonian Americans, Romanian Americans, Bulgarian Americans, and Serbian Americans. Some come from other Eastern European countries.

Judaism in the U.S.

The history of the Jews in the United States includes a religious division into Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform branches. Socially, the Jewish community began with small groups of merchants in colonial ports like New York City and Charleston. In the mid-to-late 1800s, well-educated German Jews arrived. They settled in towns and cities across the U.S., often as dry goods merchants. From 1880 to 1924, many Yiddish-speaking Jews came from Eastern Europe. They settled in New York City and other large cities. After 1926, many came as refugees from Europe. After 1980, many came from the Soviet Union, and there has been a flow from Israel. By 1900, the 1.5 million Jewish people in the United States was the third most of any nation, after Russia and Austria-Hungary. The proportion of Jewish people in the U.S. population has been about 2% to 3% since 1900. In the 21st century, Jewish people are spread out in major metropolitan areas around New York or the Northeastern United States, and especially in South Florida and California.

Church and State Issues

Religious Freedom in the Colonies

Early immigrants to the American colonies were largely motivated by the desire to worship freely. This was especially true after the English Civil War and religious wars in France and Germany. These immigrants included many nonconformists like the Puritans and the Pilgrims, as well as Roman Catholics (in Baltimore). Despite their shared background of seeking freedom, these groups had mixed views on broader religious toleration. Some, like Roger Williams of Rhode Island and William Penn, protected religious minorities in their colonies. Others, like the Plymouth Colony and Massachusetts Bay Colony, had official state churches. The Dutch colony of the New Netherlands also made the Dutch Reformed Church official and outlawed other worship. However, enforcement by the Dutch West India Company was weak in the colony's last years. One reason for having an official church was financial: the official church was responsible for helping the poor, so dissenting churches would have a big advantage.

There were also people who opposed supporting any official church, even at the state level. In 1773, Isaac Backus, a prominent Baptist minister in New England, said that when "church and state are separate, the effects are happy, and they do not at all interfere with each other." He added that when they are mixed, "no tongue nor pen can fully describe the mischiefs that have ensued." Thomas Jefferson's influential Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom was passed in 1786, five years before the Bill of Rights.

Most Anglican ministers and many Anglicans outside the South were Loyalists (loyal to Britain). The Anglican Church lost its official status during the Revolution. After separating from Britain, it was reorganized as the independent Episcopal Church.

The Establishment Clause

The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution says, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof . . ." In an 1802 letter, Thomas Jefferson used the phrase "separation of church and state" to describe the combined effect of the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Although "separation of church and state" is not in the Constitution, the U.S. Supreme Court has quoted it in several decisions.

Robert N. Bellah has argued that even though church and state are separate in the U.S. Constitution, this doesn't mean there's no religious side to American politics. He used the term Civil Religion to describe the special connection between politics and religion in the United States. His 1967 article looked at John F. Kennedy's inaugural speech. Kennedy asked, "Considering the separation of church and state, how is a president justified in using the word 'God' at all?" Bellah's answer was that the separation of church and state "has not denied the political realm a religious dimension."

This is not just a topic for sociologists. It can also be an issue for atheists in America. There are claims of discrimination against atheists in the United States.

Jefferson, Madison, and the "Wall of Separation"

The phrase "a hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world" was first used by Baptist theologian Roger Williams. He was the founder of the colony of Rhode Island. Later, Jefferson used it in an 1802 letter to explain the First Amendment's limit on the federal government.

Jefferson's and Madison's ideas of "separation" have been debated for a long time. Jefferson refused to issue Thanksgiving proclamations sent to him by Congress during his presidency. However, he did issue a Thanksgiving and Prayer proclamation as Governor of Virginia. He also vetoed two bills because he believed they violated the First Amendment.

After leaving the presidency, Madison argued for a stronger separation of church and state. He opposed presidents issuing religious proclamations, even though he had done so himself. He also opposed having chaplains in Congress.

Jefferson's opponents said his position meant rejecting Christianity, but this was an unfair description. When setting up the University of Virginia, Jefferson encouraged all different religious groups to have their own preachers. However, there was a constitutional ban on the state supporting a professorship of divinity, based on his own Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.

Supreme Court Rulings Since 1947

The phrase "separation of church and state" became a key part of how the Establishment Clause was understood in Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947). This case dealt with a state law that allowed government money for transportation to religious schools. While the ruling said the state law was constitutional, Everson was also the first case to say that the Establishment Clause applied to state governments as well as Congress. This was based on the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In 1949, reading the Bible was a routine part of public schools in at least 37 states. In 12 of these states, Bible reading was required by law; 11 states passed these laws after 1913. In 1960, 42% of school districts nationwide allowed or required Bible reading. 50% reported some form of daily prayer in homeroom.

Since 1962, the Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that prayers organized by public school officials are unconstitutional. Students are allowed to pray privately and join religious clubs after school hours. Colleges, universities, and private schools are not affected by these rulings. Reactions to these rulings were largely negative, with over 150 constitutional amendments proposed to reverse the policy. None passed Congress. The Supreme Court has also ruled that "voluntary" school prayers are unconstitutional. This is because they can make some students feel like outsiders and pressure those who disagree. In Lee v. Weisman (1992), the Supreme Court stated:

- the State may not place the student dissenter in the dilemma of participating or protesting. Since adolescents are often susceptible to peer pressure, especially in matters of social convention, the State may no more use social pressure to enforce orthodoxy than it may use direct means. The embarrassment and intrusion of the religious exercise cannot be refuted by arguing that the prayers are of a de minimis character, since that is an affront to ...those for whom the prayers have meaning, and since any intrusion was both real and a violation of the objectors' rights.

In 1962, the Supreme Court applied this idea to prayer in public schools. In Engel v. Vitale (1962), the Court decided it was unconstitutional for state officials to write an official school prayer and require it to be recited in public schools. This was true even if the prayer was non-denominational and students could choose not to participate. However, any teacher, staff member, or student can pray in school according to their own religion. But they cannot lead such prayers in class or in other "official" school settings like assemblies or programs.

Currently, the Supreme Court uses a three-part test, called the "Lemon Test", to decide if a law follows the Establishment Clause. First, the law must have been passed for a neutral or non-religious reason. Second, the law's main effect must not promote or hinder religion. Third, the law must not cause too much mixing of government and religion.

Islam in the U.S.

The first significant migration of Muslims to America is thought to have started around 1820 (or 1860). These Muslims came from Syria, Lebanon, Albania, Macedonia, Turkey, and other regions. From that time on, Islam gradually became more widely known in America. However, records suggest the first Muslim person in America arrived in 1520 (a Moroccan Muslim).

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |