Joseph Smith facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Joseph Smith |

|

|---|---|

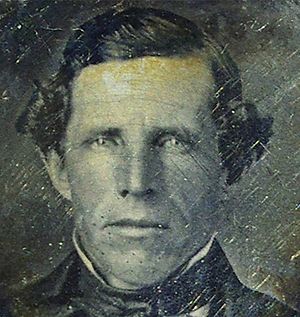

Portrait, c. 1842

|

|

| 1st President of the Church of Christ (later the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) | |

| April 6, 1830 – June 27, 1844 | |

| Successor | Disputed; Brigham Young, Sidney Rigdon, Joseph Smith III, and at least four others each claimed succession. |

| End reason | Death |

| 2nd Mayor of Nauvoo, Illinois | |

| In office | |

| May 19, 1842 – June 27, 1844 | |

| Predecessor | John C. Bennett |

| Successor | Chancy Robison |

| Political party | Independent |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joseph Smith Jr. December 23, 1805 Sharon, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died | June 27, 1844 (aged 38) Carthage, Illinois, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Resting place | Smith Family Cemetery, Nauvoo, Illinois, U.S. 40°32′26″N 91°23′33″W / 40.54052°N 91.39244°W |

| Spouse(s) |

Multiple others (about 32–46; exact number debated) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805 – June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader. He founded Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time he died 14 years later, he had tens of thousands of followers. The religion he started still exists today, with millions of members worldwide.

Smith was born in Sharon, Vermont. His family moved to Western New York in 1816 after several years of bad harvests. This area was very active with religious revivals during the Second Great Awakening. Smith said he had a series of visions. The first one was in 1820. He described seeing "two personages," whom he later identified as God the Father and Jesus Christ. In 1823, he said an angel visited him. This angel told him about a buried book of golden plates. These plates were said to contain a Judeo-Christian history of an ancient American civilization.

In 1830, Smith published an English translation of these plates, called the Book of Mormon. That same year, he organized the Church of Christ. He called it a restoration of the early Christian Church. Members were later called "Latter Day Saints" or "Mormons." In 1838, Smith announced a revelation renaming the church to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

In 1831, Smith and his followers moved west. They planned to build a communal American Zion. They first gathered in Kirtland, Ohio. They also set up an outpost in Independence, Missouri, meant to be Zion's "center place." During the 1830s, Smith sent out missionaries and published revelations. He also oversaw the building of the Kirtland Temple. Due to financial problems and conflicts with non-Mormons, Smith and his followers moved again. They established a new settlement in Nauvoo, Illinois. Smith became its spiritual and political leader.

In 1844, a newspaper called the Nauvoo Expositor criticized Smith's power. It also mentioned his controversial practice of marrying multiple wives. Smith and the Nauvoo city council ordered the destruction of its printing press. This made anti-Mormon feelings much stronger. Fearing an attack on Nauvoo, Smith went to Carthage, Illinois, to face trial. However, he was killed when a mob stormed the jailhouse.

During his time as a religious leader, Smith published many texts. He said many of these came from divine inspiration and revelation from God. He dictated most of them in the first person. He said they were writings of ancient prophets or the voice of God. His followers believed his teachings were prophetic. Several of these texts became scripture for Latter Day Saint groups. Smith's teachings discussed God, the universe, family, government, and religious community. Mormons generally see him as a prophet like Moses and Elijah. Several religious groups today consider themselves a continuation of the church he started. These include the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and the Community of Christ.

Contents

Life of Joseph Smith

Early Years and Visions (1805–1827)

Joseph Smith Jr. was born on December 23, 1805. His parents were Lucy Mack Smith and Joseph Smith Sr.. He was one of 11 children. When he was seven, Smith had a serious bone infection. He used crutches for three years after surgery.

After some bad business and three years of failed crops, the Smith family left Vermont. They moved to Western New York in 1816. They bought a 100-acre (40 ha) farm in Palmyra and Manchester. This area was full of religious excitement during the Second Great Awakening.

Smith said he became interested in religion by age 12. As a teenager, he might have liked Methodism. His family also practiced some religious folk magic. This was common at the time. Smith said he was confused by all the different church claims.

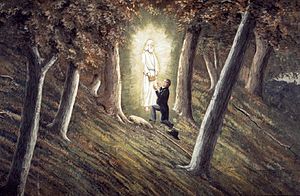

Years later, Smith wrote about a vision that helped him. He said in 1820, while praying in a wooded area, God and Jesus Christ appeared to him. They told him his sins were forgiven. They also said all churches at the time had "turned aside from the gospel." Smith said he told a minister, who "dismissed the story with great contempt." He kept it private for about ten years because of this. Later, he shared it with followers. This first vision became very important to his followers. They saw it as the start of the restoration of Christ's church.

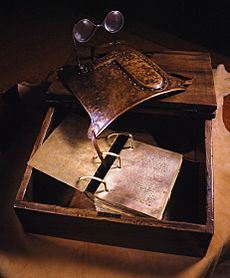

Smith later said that in 1823, an angel named Moroni visited him. This angel told him where to find a buried book of golden plates. He also found other items, like a breastplate and interpreters. These were two seer stones in a frame. They were hidden in a hill near his home. Smith said he tried to get the plates the next morning but couldn't. The angel stopped him. He reported visiting the hill yearly for four years. Each time, he returned without the plates until the last visit.

The Smith family faced money problems. Smith's older brother, Alvin, who helped lead the family, died. Family members earned money by doing odd jobs and searching for treasure. Smith was said to find lost items by looking into a seer stone. He used this for treasure hunting. In 1825, he joined Josiah Stowell, a wealthy farmer, in unsuccessful attempts to find buried treasure. In 1826, Smith was accused in court of "glass-looking," or pretending to find treasure. The outcome of this case is not fully clear.

While staying at the Hale house in Pennsylvania, Smith met Emma Hale. Her father, Isaac Hale, did not approve of their marriage. He thought Smith couldn't support Emma. Smith and Emma ran away and married on January 18, 1827. They then lived with Smith's parents. Later, Smith promised to stop treasure seeking. Hale then let them live on his property in Harmony.

Smith made his last visit to the hill on September 22, 1827. He took Emma with him. This time, he said he successfully got the plates. He said the angel told him not to show the plates to anyone. He was to translate them and publish the translation. Smith said the plates were a religious record of ancient Americans. They were written in an unknown language called reformed Egyptian. He told friends he could read and translate them.

Smith's former treasure-seeking partners believed he had tricked them. They thought the golden plates should be shared. After they searched places where the plates might be hidden, Smith decided to leave Palmyra.

Starting a New Church (1827–1830)

In October 1827, Smith and Emma moved from Palmyra to Harmony, Pennsylvania. A neighbor, Martin Harris, helped them. Living near Emma's family, Smith copied some characters from the plates. He dictated their translations to Emma.

In February 1828, Harris visited Harmony. He took a sample of the characters Smith had copied to scholars. Harris said a scholar named Charles Anthon first confirmed the characters. But Anthon later changed his mind when he heard Smith claimed to get the plates from an angel. Anthon denied Harris's story. Harris returned to Harmony in April 1828 and became Smith's scribe.

Harris and his wife Lucy started to doubt the plates existed. Harris convinced Smith to let him take 116 pages of the manuscript to Palmyra. He wanted to show them to family. The manuscript was lost while Harris had it. Smith was very upset, especially since his first son had just died. Smith said the angel took the plates away as punishment. During this time, Smith briefly attended Methodist meetings with Emma.

Smith said the angel returned the plates in September 1828. He then dictated some of the book to Emma. In April 1829, Smith met Oliver Cowdery. Cowdery also had an interest in folk magic. With Cowdery as scribe, Smith began translating very quickly. They worked full-time on the manuscript until early June 1829. Then they moved to Fayette, New York. They continued the work at the home of Cowdery's friend, Peter Whitmer. When the story mentioned a church and baptism, Smith and Cowdery baptized each other. The dictation finished around July 1, 1829.

Smith had not shown the plates to anyone before. But he told Martin Harris, Oliver Cowdery, and David Whitmer they could see them. These men, called the Three Witnesses, signed a statement. They said an angel showed them the golden plates. They also said God's voice confirmed the translation was true. Later, a group of Eight Witnesses—family members of Whitmer and Smith—said Smith showed them the plates. Smith said the angel Moroni took the plates back after he finished using them.

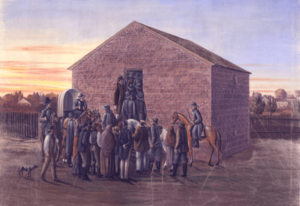

The finished book, titled the Book of Mormon, was published in Palmyra. It was first advertised on March 26, 1830. Less than two weeks later, on April 6, 1830, Smith and his followers formally organized the Church of Christ. Small groups were started in Manchester, Fayette, and Colesville, New York. The Book of Mormon made Smith well-known. It also brought back anger from those who remembered his 1826 court case. After Cowdery baptized new members, Mormons faced threats. Smith was arrested and accused of being a "disorderly person." He was found not guilty, but he and Cowdery fled to Colesville to escape a mob. Smith later said that around this time, Peter, James, and John appeared to him. They ordained him and Cowdery to a higher priesthood.

Other church members, like Cowdery and Hiram Page, also claimed to receive revelations. Smith responded by dictating a revelation. It said his role was a prophet and an apostle. It also stated that only he could declare church doctrine and scripture. Smith then sent Cowdery and others on a mission to share their beliefs with Native Americans. Cowdery was also told to find the site of the New Jerusalem.

On their way to Missouri, Cowdery's group passed through Ohio. There, Sidney Rigdon and over a hundred of his followers converted to Mormonism. This more than doubled the church's size. Rigdon soon became Smith's main helper. With growing opposition in New York, Smith announced a revelation. It said his followers should gather in Kirtland, Ohio. They were to settle there and wait for news from Cowdery's mission.

Life in Ohio (1831–1838)

When Smith moved to Kirtland, Ohio in January 1831, he found a religious culture with strong displays of spiritual gifts. These included trances and speaking in tongues. Rigdon's followers were practicing a form of communal living. Smith brought the Kirtland group under his leadership. He calmed the excited outbursts. Smith had promised church elders they would receive an endowment of heavenly power in Kirtland. In June 1831, he introduced the greater authority of a High Priesthood to the church.

Many new members came to Kirtland. By summer 1835, there were 1,500 to 2,000 Mormons nearby. Many expected Smith to lead them to a Millennial kingdom soon. Cowdery and other missionaries were tasked with finding a site for "a holy city." They found Jackson County, Missouri. After Smith visited in July 1831, he declared Independence the "center place" of Zion. For most of the 1830s, the church was based in Ohio. Smith lived there, though he visited Missouri in 1832. This was to stop a rebellion of church members who felt neglected. Smith's trip was rushed because a mob in Ohio was angry about his power. The mob attacked Smith and Rigdon, leaving them for dead.

In Jackson County, Missouri residents did not like the Mormon newcomers. Tensions grew until July 1833. Non-Mormons forced Mormons out and destroyed their property. Smith told his followers to be patient. After many attacks, they could fight back. Armed groups exchanged fire, and people were killed. The old settlers then forced Mormons out of the county.

Smith led a small group called Zion's Camp to help the Missouri Mormons. This military effort failed. The men were not well organized, suffered from cholera, and were outnumbered. Smith sent church representatives to ask the Missouri governor for help. But the governor refused. By late June, Smith ended the conflict and disbanded Zion's Camp. Still, Zion's Camp was important. Many future church leaders came from its participants.

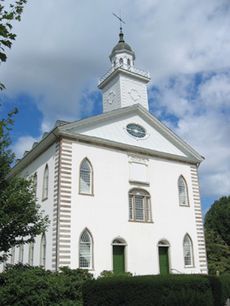

After the Camp returned to Ohio, Smith used its members to form church governing bodies. Smith said that to "redeem Zion," his followers needed an endowment in the Kirtland Temple. In March 1836, at the temple's dedication, many reported seeing angels. They also prophesied and spoke in tongues.

In late 1837, problems within the church led to the Kirtland community's collapse. Smith was blamed for promoting a church-sponsored bank that failed. Building the temple left the church deeply in debt. Smith was pursued by people he owed money to. He heard about hidden money in Salem, Massachusetts. Smith traveled there and announced a revelation that God had "much treasure in this city." But he returned to Kirtland empty-handed after a month.

In January 1837, Smith and other church leaders started a company. It was called the Kirtland Safety Society. It acted like a bank. The company issued banknotes partly backed by real estate. Smith encouraged Latter Day Saints to buy the notes. He invested heavily himself. The bank failed within a month. Many Latter Day Saints in Kirtland lost money. Smith was held responsible. Many people left the church, including close advisors. A warrant was issued for Smith's arrest for banking fraud. Smith and Rigdon fled Kirtland for Missouri in January 1838.

Life in Missouri (1838–1839)

By 1838, Smith had given up plans to "redeem Zion" in Jackson County. After Smith and Rigdon arrived in Missouri, the town of Far West became the new "Zion." The church also took the name "Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints." Construction began on a new temple. Thousands of Latter Day Saints followed them from Kirtland. Smith encouraged settlement outside Caldwell County, starting a community in Adam-ondi-Ahman.

During this time, a church council removed many older church leaders. Smith approved of removing these men, called "dissenters."

Differences between old Missouri residents and new Mormon settlers caused problems. Smith's past experiences with mob violence made him believe his faith needed to be stronger against anti-Mormons. Around June 1838, Sampson Avard formed a secret group called the Danites. They aimed to scare Mormon dissenters and fight anti-Mormon groups. It's not clear how much Smith knew of all Danite actions, but he approved of what he did know. After Rigdon gave a sermon suggesting dissenters had no place, the Danites forced them out.

In a speech at Far West, Rigdon said Mormons would no longer tolerate being treated badly. He spoke of a "war of extermination" if Mormons were attacked. Smith supported this speech. Many non-Mormons saw it as a threat. This led to strong anti-Mormon talk in newspapers and speeches.

On August 6, 1838, non-Mormons in Gallatin tried to stop Mormons from voting. This led to fights and started the 1838 Mormon War. Non-Mormon groups attacked and burned Mormon farms. Danites and other Mormons also attacked non-Mormon towns. In the Battle of Crooked River, Mormons attacked the state militia by mistake. Governor Lilburn Boggs then ordered Mormons to be "exterminated or driven from the state." On October 30, Missourians killed seventeen Mormons in the Haun's Mill massacre.

The next day, Latter Day Saints surrendered to state troops. They agreed to give up their property and leave the state. Smith was immediately accused of treason and sentenced to be executed. But Alexander Doniphan, Smith's former lawyer and a general, refused the order. Smith was then sent to a state court. Several former allies testified against him. Smith and five others, including Rigdon, were charged with treason. They were sent to the jail in Liberty, Missouri, to await trial.

Smith's time in prison was difficult. Meanwhile, Brigham Young became prominent. He organized the move of about 14,000 Mormon refugees to Illinois and Iowa.

Smith handled his imprisonment well. He knew he was on trial before his own people. Many thought he was a failed prophet. He wrote a defense and an apology for the Danites' actions. He said, "The keys of the kingdom have not been taken away from us." He told his followers to collect stories of their persecution. But he also urged them to be less angry toward non-Mormons. On April 6, 1839, Smith and his companions escaped custody. This likely happened with help from the sheriff and guards.

Life in Nauvoo, Illinois (1839–1844)

Many American newspapers criticized Missouri for the Haun's Mill massacre. Illinois welcomed Mormon refugees. They gathered along the Mississippi River. Smith bought swampy land in Commerce, which he renamed "Nauvoo" (meaning "to be beautiful"). Smith tried to show Latter Day Saints as an oppressed group. He asked the federal government for help but did not get reparations. In summer 1839, Mormons in Nauvoo suffered from malaria. Smith sent Brigham Young and other apostles on missions to Europe. They gained many new members, often poor factory workers.

Smith also attracted some wealthy and powerful converts. These included John C. Bennett, an Illinois official. Bennett used his connections to get a very generous charter for Nauvoo. The charter gave the city almost complete independence. It allowed a university and gave Nauvoo habeas corpus power. This helped Smith avoid being sent back to Missouri. The charter also allowed the Nauvoo Legion, a militia. Smith and Bennett became its commanders. They controlled the largest armed group in Illinois. Smith made Bennett an Assistant President of the church. Bennett was also elected Nauvoo's first mayor.

The early Nauvoo years brought new church teachings. Smith introduced baptism for the dead in 1840. In 1841, construction began on the Nauvoo Temple. It was meant to be a place to regain lost ancient knowledge. A revelation in 1841 promised to restore the "fullness of the priesthood." In May 1842, Smith started a revised endowment ceremony. This ceremony was similar to freemasonry rites Smith had seen. At first, only men could receive the endowment. They joined a group called the Anointed Quorum. For women, Smith started the Relief Society. He said women in this group would receive "the keys of the kingdom."

Smith also explained his plan for a millennial kingdom. He no longer saw Zion as just Nauvoo. He saw Zion as all of North and South America. Mormon settlements would be "stakes" of Zion's tent. Zion became less a refuge and more a great building project. In summer 1842, Smith revealed a plan to establish God's kingdom. It would eventually rule the whole Earth.

Smith also began secretly marrying additional wives. This practice was called plural marriage. He shared this teaching with a few close friends, including John Bennett. When rumors of this practice spread, Smith forced Bennett to resign as Nauvoo mayor. Bennett then left Nauvoo and published accusations against Smith.

By mid-1842, public opinion turned against Mormons. After someone shot Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs in May 1842, rumors spread. Anti-Mormons said Smith's bodyguard, Porter Rockwell, was the shooter. Boggs ordered Smith's arrest and transfer to Missouri. Smith hid twice. Later, a U.S. attorney said sending Smith to Missouri would be unconstitutional. (Rockwell was later found not guilty.) In June 1843, Smith's enemies convinced Illinois Governor Thomas Ford to send Smith to Missouri. This was for an old treason charge. Two officers arrested Smith. But a group of Mormons stopped them before they reached Missouri. Smith was then released by a Nauvoo court order. This stopped Missouri's attempts to arrest him. But it caused political problems in Illinois.

In December 1843, Smith asked Congress to make Nauvoo an independent territory. It would have the right to call on federal troops. Smith then wrote to presidential candidates. He asked what they would do to protect Mormons. After getting unclear answers, Smith announced his own candidacy for President of the United States. He stopped regular missionary work. He sent out church leaders and hundreds of other political missionaries. In March 1844, Smith organized the secret Council of Fifty. Smith said the Council could decide which laws Mormons should obey. The Council was also to choose a site for a large Mormon settlement. This would be in Texas, California, or Oregon. Mormons could live there under their own laws.

Death of Joseph Smith

By early 1844, problems arose between Smith and some close friends. William Law, Smith's counselor, and Robert Foster, a general, disagreed with Smith. They disagreed on how to manage Nauvoo's economy. Both also said Smith had proposed marriage to their wives. Smith believed these men were plotting against him. He removed them from the church on April 18, 1844. They formed a new church. The next month, they got charges against Smith for lying (as Smith publicly denied having more than one wife) and marrying multiple wives.

On June 7, these former members published the Nauvoo Expositor newspaper. It called for changes within the church. It also appealed to non-Mormons. The paper criticized Smith's "doctrines of many Gods." It hinted at Smith's desire for religious rule. It also called for removing Nauvoo's city charter. It attacked Smith's practice of marrying multiple wives.

Smith feared the newspaper would cause new violence. The Nauvoo city council declared the Expositor a public problem. They ordered the Nauvoo Legion to destroy the press. Smith strongly urged the council to destroy the press. He did not realize that destroying a newspaper would likely cause more trouble than the accusations themselves.

Destroying the newspaper led to a strong call to action from Thomas C. Sharp. He was the editor of the Warsaw Signal and a long-time critic of Smith. Fearing mob violence, Smith called up the Nauvoo Legion on June 18. He declared martial law. Officials in Carthage called up a small state militia. Governor Thomas Ford stepped in. He threatened to raise a larger militia unless Smith and the Nauvoo city council surrendered. Smith first fled across the Mississippi River. But he soon returned and surrendered to Ford. On June 25, Smith and his brother Hyrum arrived in Carthage. They were to stand trial for causing a riot. Once they were in custody, the charges were increased to treason. This stopped them from getting bail. John Taylor and Willard Richards stayed with the Smiths in Carthage Jail.

On June 27, 1844, an armed mob stormed Carthage Jail. Joseph and Hyrum were held there. Smith fired three shots from a pistol, wounding three men. Then he tried to jump out the window. He was shot many times before falling out. He died shortly after hitting the ground. Five men were tried for Smith's murder, but all were found not guilty.

After his death, non-Mormon newspapers mostly called Smith a religious fanatic. But within Mormonism, Smith was seen as a prophet. He was considered a martyr who died for his faith.

After a public funeral, Emma Smith secretly buried their remains at night. The bodies were later moved and reburied. In 1928, members of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS Church) found and reburied the Smith brothers' remains. Emma Smith was also reinterred with them in Nauvoo at the Smith Family Cemetery.

Joseph Smith's Legacy

His Influence and How He is Seen Today

Joseph Smith gained thousands of devoted followers before his death in 1844. Millions more followed in the next century. Among Mormons, he is seen as a prophet, like Moses and Elijah. In 2015, Smithsonian magazine ranked Smith first among religious figures in its "100 Most Significant Americans of All Time."

In the 1800s, people often dismissed Smith. For example, Philip Schaff called him an "uneducated but cunning Yankee." He thought the growth of the Latter Day Saint movement was embarrassing for America. Early 1900s writers suggested Smith had health issues like epileptic seizures or mental health problems. They thought this might explain his visions. Fawn Brodie's 1945 book No Man Knows My History said Smith was a clever fraud. After academic studies of Mormonism grew, two views of Smith appeared. One saw him as a fraud who tricked people. The other saw him as a man of God with great character. Historian Jan Shipps called this "the prophet puzzle."

In the 21st century, scholars are more interested in understanding Smith's experiences. They study his influence on American religious history. Biographers, both Mormon and non-Mormon, agree Smith was very influential. He was a charismatic and creative figure in American religion. For example, Wayne Hudson, a scholar, calls Smith "a genuine prophet of world historical importance." Theologian Douglas J. Davies describes Smith as having striking "moral energy" and courage. Historian Laurie Maffly-Kipp says Richard Bushman's 2005 book Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling is "the definitive account" of Smith's life. This book discusses Smith's financial troubles and legal issues. But it also argues that Smith's religious ideas were consistent and appealing.

Historian John G. Turner noted that outside of universities, non-Mormons in the U.S. often see Smith as a "charlatan, scoundrel, and heretic." Outside the U.S., he is "obscure." Smith's legacy varies among different Latter Day Saint groups. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) sees Smith as their founding prophet. LDS apostle D. Todd Christofferson said Latter-day Saints "readily acknowledge" Smith's "continuing influence for good in the world." They also recognize his revelations, service, and devotion to God.

Smith's reputation in the Community of Christ is mixed. This church never accepted Smith's later religious ideas from Nauvoo. Later changes in their beliefs further separated them from Smith. The Community of Christ still honors his role in founding the church. But they focus more on Jesus Christ than on human leaders like Smith. Some groups, like Woolleyite Mormon fundamentalism, even consider Smith a god.

Memorials to Smith include the Joseph Smith Memorial Building in Salt Lake City, Utah. There is also the Joseph Smith Building at Brigham Young University. A granite monument marks Smith's birthplace. There is also a bronze statue of him in the World Peace Dome in Pune, India.

Successors and Church Groups

Smith's death led to a problem over who would lead the church. Smith had suggested several ways to choose his successor. But he never made his preference clear. His brother Hyrum, if he had lived, would have had the strongest claim. Then came his brother Samuel, who died soon after Joseph and Hyrum. Another brother, William, could not gain enough followers. Smith's sons Joseph III and David were too young. Joseph was 11, and David was born after Smith's death.

The two strongest candidates were Brigham Young and Sidney Rigdon. Young was the senior member and president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Rigdon was the senior remaining member of the First Presidency. At a church meeting on August 8, most Latter Day Saints present chose Young. They eventually left Nauvoo and settled in the Salt Lake Valley. Young's church, named The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), had over 16 million members in 2018. Smaller groups followed Sidney Rigdon and James J. Strang. Strang claimed leadership based on a letter he said Smith wrote. Some scholars believe this letter was fake. Some hundreds followed Lyman Wight to Texas. Others followed Alpheus Cutler. Many members of these smaller groups, including most of Smith's family, joined together in 1860. They followed Joseph Smith III and formed the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. This church was later renamed the Community of Christ. It now has about 250,000 members.

Family Life

Joseph Smith's first wife, Emma Hale, had nine children during their marriage. Five of them died before age two. The oldest, Alvin (born 1828), died hours after birth. Twins Thaddeus and Louisa (born 1831) also died. When the twins died, the Smiths adopted another set of twins, Julia Murdock and Joseph Murdock. Their mother had died in childbirth. Joseph Murdock Smith died of measles in 1832. In 1841, Don Carlos, born a year earlier, died of malaria. Five months later, in 1842, Emma had a stillborn son.

Joseph and Emma had five children who lived to adulthood: adopted Julia Murdock, Joseph Smith III, Frederick Granger Williams Smith, Alexander Hale Smith, and David Hyrum Smith. Some historians think Smith might have had children with other wives. However, DNA tests of possible descendants from other wives have been negative.

After Smith's death, Emma Smith became separated from Brigham Young and the church leaders. Emma feared Young, and he was suspicious of her. She wanted to keep the family's money separate from the church's. He also disliked her open opposition to marrying multiple wives. Young kept Emma Smith out of church meetings and social events. When most Latter Day Saints moved west, she stayed in Nauvoo. She married a non-Mormon, Major Lewis C. Bidamon. Emma Smith left religion until 1860. Then she joined the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Her son, Joseph Smith III, led this church. Emma believed Smith had been a prophet. She never said the Book of Mormon was not real.

Plural Marriage

Some accounts say Smith taught about marrying multiple wives as early as 1831. There is evidence he may have practiced it by 1835. The church publicly said it did not support this practice. But in 1837, there was a disagreement between Smith and Oliver Cowdery about it.

In April 1841, Smith secretly married Louisa Beaman. Over the next two and a half years, he secretly married or was "sealed" to about 30 or 40 more women. Ten of these women were between 14 and 20 years old. Others were over 50. Ten were already married to other men. Some of these marriages were with the first husband's permission. Some of these marriages may have been seen as special religious marriages that would only take effect after death. During Smith's life, this practice was kept secret from non-Mormons and most church members.

This practice caused problems between Smith and his first wife, Emma. Historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich says Emma sometimes accepted these marriages and sometimes resisted. Emma knew about some of her husband's marriages. But she likely did not know the full extent of his activities. In 1843, Emma briefly accepted Smith marrying four women she chose. They lived in the Smith home. But she later regretted it and asked the other wives to leave. That July, Joseph dictated a revelation telling Emma to accept plural marriage. Hyrum delivered the message, but Emma strongly rejected it. Joseph and Emma did not make up until September 1843. This was after Emma started participating in temple ceremonies and after Joseph made other agreements with her. In March 1844, Emma publicly spoke against plural marriage. She did not directly reveal his secret practice. But she insisted people should only listen to what Smith taught publicly. This challenged Smith's private teachings.

Despite knowing about it, Emma Smith publicly denied her husband ever took other wives. While Joseph Smith was alive, Emma spoke against plural marriage. She signed a petition in 1842 denying that Smith or his church supported the practice. After Smith's death, Emma continued to deny his plural marriages. When her sons asked her about it, she said, "No such thing as polygamy, or spiritual wifery, was taught, publicly or privately, before my husband's death, that I have now, or ever had any knowledge of ... He had no other wife but me; nor did he to my knowledge ever have."

Joseph Smith's Revelations

Historian Richard Bushman says the main feature of Smith's life was "his sense of being guided by revelation." Instead of using logic, Smith dictated scripture-like "revelations." He let people decide whether to believe. Smith and his followers saw his revelations as higher than teachings or opinions. Smith acted as if he believed his revelations as much as his followers. Smith's first recorded revelation was a warning. It criticized him for letting Martin Harris lose 116 pages of the Book of Mormon manuscript. This revelation was written as if God were speaking. Later revelations used a similar style. They often began with words like "Hearken O ye people which profess my name, saith the Lord your God."

The Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon is called the longest and most complex of Smith's revelations. Its language is like the King James Version of the Bible. It is organized as a collection of smaller books. Each is named after important people in the story. This is similar to the Bible. However, this collection is a "uniform whole." It tells the story of a religious civilization. It begins around 600 BC and ends in the fifth century. The story starts with a family leaving Jerusalem before the Babylonian captivity. They build a ship and sail to a "promised land" in the Western Hemisphere. There, they divide into two groups: Nephites and Lamanites. The Nephites become a righteous people. They build a temple and follow the law of Moses. Their prophets teach a Christian gospel. The book says it is mostly the work of Mormon, a Nephite prophet. The book ends when Mormon's son, Moroni, finishes writing and buries the records.

Christian ideas are throughout the book. For example, Nephite prophets teach about Christ's coming. They talk about the star that will appear at his birth. After Jesus's crucifixion and resurrection in Jerusalem, he appears in the Americas. He repeats the Sermon on the Mount, blesses children, and appoints twelve disciples. The book ends with Moroni telling people to "come unto Christ."

Early Mormons saw the Book of Mormon as a companion to the Bible. They saw it as a religious history of ancient Americans. Parley P. Pratt said the book "filled my soul with joy and gladness." He valued the book "more than all the riches of the world." Other readers thought the book was from a fanatic or a fraud. They thought it was based on Smith's surroundings. Alexander Campbell said Smith wrote "every error and almost every truth discussed in New York for the last ten years" in his book.

Some scholars see the Book of Mormon as a response to issues of Smith's time. Historian Dan Vogel sees the book as reflecting Smith's own life. Biographer Robert V. Remini calls the Book of Mormon "a typically American story." He says it shows the religious excitement of the Second Great Awakening. Brodie suggested Smith wrote the book using sources like the 1823 book View of the Hebrews. Other scholars say the Book of Mormon is more inspired by the Bible than by American ideas. Richard Bushman writes that the Book of Mormon is not a typical American book. He says its "innermost structure" is more like the Bible. According to historian Daniel Walker Howe, the book's main ideas are "biblical, prophetic, and patriarchal." They are not democratic or optimistic like the culture of the time. Jan Shipps argues that the Book of Mormon's "complex set of religious claims" created a "new mythos" or "story." Early converts accepted this story and lived by it.

Smith never fully explained how he produced the Book of Mormon. He only said he translated by God's power. He hinted that he read its words. The Book of Mormon itself says its text will "come forth by the gift and power of God." So, there is disagreement about the exact method. For some early dictation, Smith's friends said he used the "Urim and Thummim." These were a pair of seer stones he said were buried with the plates. However, people close to Smith said that later, he used a brown stone he found in 1822. He had used this stone before for treasure hunting. Joseph Knight said Smith saw the words of the translation. He would look at the stone or stones in the bottom of his hat, blocking out light. This was similar to finding treasure. Sometimes, Smith hid the process by using a curtain. Other times, he dictated in front of witnesses while the plates were covered or hidden. After finishing the translation, Smith gave the brown stone to Cowdery. But he continued to receive revelations using another stone until about 1833. He then said he no longer needed it.

The Book of Mormon became important in the church Smith founded. It brought some people to the movement. Some members used Book of Mormon phrases in their speech. Its description of a Christian church gave an early model for the Church of Christ's organization. For early Mormons, the book proved Smith's claims to be a prophet. Smith accepted the world described by the Book of Mormon as his own. He took on the role it described for him: a prophet, seer, and translator. By early 1831, he called himself "Joseph the Prophet." Smith confidently shared his revelations. He spoke as if he were an Old Testament prophet. The authoritative language in Smith's revelations attracted new members.

Bible Revision

In June 1830, Smith dictated a revelation. In it, Moses describes a vision. He sees "worlds without number" and talks with God. They discuss the purpose of creation and humans' relation to God. This revelation started a revision of the Bible. Smith worked on it off and on until 1833. It was not published until after his death. Smith told his followers this "new translation" would be published "as soon the Lord permit." He may have thought it was complete. But Emma Smith said the biblical revision was still unfinished when Joseph died.

While producing the Book of Mormon, Smith said the Bible was missing "the most plain and precious parts of the gospel." He said his "new translation" of the Bible would fix this. He did not translate from other languages. Instead, he changed and added to a King James Bible. He and Latter Day Saints believed this process was guided by inspiration. Many changes fixed contradictions or clarified things. Other changes added large parts to the text. For example, Smith's revision almost tripled the length of the first five chapters of Genesis. This text was called the Book of Moses.

Book of Moses

The Book of Moses starts with Moses speaking with God "face to face." He sees a vision of all existence. Moses is first overwhelmed by the vastness of the universe. But God explains that he made Earth and heavens to bring humans to eternal life. The book then gives a longer account of the Genesis creation narrative. It describes God as having a physical body. It also describes the fall of Adam and Eve in a positive way. It emphasizes eating the forbidden fruit as gaining knowledge and becoming more like God.

The Book of Moses also expands the story of Enoch. Enoch is described in the Bible as an ancestor of Noah. In the expanded story, Enoch has a vision of God. He learns that God can feel sorrow and weep. Human sin and suffering cause God to grieve. Enoch then receives a prophetic calling. He eventually builds a city of Zion. This city is so righteous that it is taken to heaven. Enoch's example inspired Smith's hope to build the Church of Christ as a Zion community. The book also explains some Bible passages that hinted at Christ's coming. It makes them clear Christian knowledge of Jesus as a Savior. This effectively "Christianizes" the Old Testament.

Book of Abraham

In 1835, Smith encouraged some Latter Day Saints to buy ancient Egyptian papyri rolls. They bought them from a traveling exhibitor. Smith said they contained writings of ancient leaders Abraham and Joseph. Over the next few years, Smith dictated what he said was a translation of one roll. It was published in 1842 as the Book of Abraham. The Book of Abraham talks about the founding of Abraham's nation. It also discusses astronomy, the universe, family lines, and priesthood. It gives another account of the creation story.

The papyri linked to the Book of Abraham were thought lost in the Great Chicago Fire. But several pieces were found again in the 1960s. Egyptologists found them to be part of the Egyptian Book of Breathing. They had no connection to Abraham.

Other Teachings

According to Parley P. Pratt, Smith dictated his revelations. A scribe recorded them without changes. Revelations were copied and shared among church members. Smith's revelations often answered specific questions. He described the process as "pure Intelligence" flowing into him. However, Smith never thought the exact words were perfect. The revelations were not God's exact words. They were "couched in language suitable to Joseph's time." In 1833, Smith edited and expanded many revelations. He published them as the Book of Commandments. This later became part of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Smith gave different types of revelations. Some were about daily life, others about spiritual matters or beliefs. Some were for one person, others for the whole church. An 1831 revelation called "The Law" gave directions for missionary work. It included rules for organizing society in Zion. It repeated the Ten Commandments. It also told members to "administer to the poor and needy." It outlined the law of consecration. An 1832 revelation called "The Vision" added to ideas of sin and forgiveness. It introduced beliefs about life after salvation, exaltation, and a heaven with degrees of glory. Another 1832 revelation first explained priesthood beliefs. Three months later, Smith gave a long revelation called the "Olive Leaf." It discussed light, truth, intelligence, and becoming holy. A related revelation in 1833 put Christ at the center of salvation.

Also in 1833, during a time of temperance (avoiding alcohol), Smith gave a revelation. It was called the "Word of Wisdom." It advised a diet of healthy herbs, fruits, grains, and little meat. It also suggested avoiding "strong" alcoholic drinks, tobacco, and "hot drinks" (later meaning tea and coffee). The Word of Wisdom was first a suggestion, not a rule. Smith and early Latter Day Saints did not always follow it strictly. But it later became a requirement in the LDS Church. In 1835, Smith gave the "great revelation." It organized the priesthood into quorums and councils. It was a detailed plan for church structure. Smith's last revelation, on the "New and Everlasting Covenant," was recorded in 1843. It dealt with family beliefs, the doctrine of sealing, and plural marriage.

Before 1832, most of Smith's revelations were about starting the church. They also focused on gathering followers and building the City of Zion. Later revelations mainly dealt with the priesthood, endowment, and exaltation. The number of formal written revelations slowed after 1833. Smith taught more in sermons, conversations, and letters. For example, the ideas of baptism for the dead and God's nature were introduced in sermons. One of Smith's famous statements, about there being "no such thing as immaterial matter," came from a casual conversation.

Joseph Smith's Views and Teachings

God and the Universe

Smith taught that everything was material, even a world of "spirit matter." This matter was so fine it was invisible to most eyes. Smith believed matter could not be created or destroyed. Creation only involved reorganizing existing matter. Like matter, Smith saw "intelligence" as always existing with God. He taught that human spirits came from a pre-existent pool of eternal intelligences. However, spirits could not feel "fullness of joy" without physical bodies. So, God's work was to create worlds where spirits could get bodies.

Historians have discussed Smith's early ideas of God. Some say in the early-to-mid-1830s, Smith saw God the Father as a spirit. But others argue that revelations he dictated as early as 1830 described God as a physical being. Catholic philosopher Stephen H. Webb says Smith had a "corporeal and anthropomorphic understanding of God." This was shown in his 1830 Book of Moses. It described God as a physical being who looks like humans. Steven C. Harper states that in the 1830s, Smith privately described his 1820 first vision. He said it was a vision of "two divine, corporeal beings." This showed his early ideas about God's physical nature.

Over time, Smith clearly taught that God was an advanced, glorified man. He had a body and existed in time and space. By 1841, he publicly taught that God the Father and Jesus were separate beings with physical bodies. However, he saw the Holy Spirit as a "personage of Spirit." Smith extended this idea to all existence. He taught that "all spirit is matter." This meant a person's physical body was not a sign of sin. It was a divine quality humans shared with God. Humans are not just God's creations. They are God's "kin." There is also evidence that Smith taught, to some people, that God the Father had a God the Mother with him. In this view, God is plural, has a body, has gender, and is both male and female.

Through gaining knowledge, those who received exaltation could become like God. These teachings suggested a vast group of gods. God himself had a father. In Smith's view of the universe, those who became gods would rule. They would be united in purpose. They would lead spirits of lesser ability to share immortality and eternal life.

Smith believed everyone had a chance to achieve exaltation. Those who died without a chance to accept saving ceremonies could do so after death. This would happen through proxy ceremonies done for them. Smith said children who died young would be guaranteed to rise at the resurrection and receive exaltation. Except for those who committed the eternal sin, Smith taught that even wicked people would achieve a degree of glory in the afterlife.

Religious Authority and Rituals

Smith's teachings were based on dispensational restorationism. He taught that the Church of Christ, restored through him, was a latter-day restoration of early Christian faith. This faith had been lost in the Great Apostasy. At first, Smith's church had little structure. His religious authority came from his visions and revelations. Smith did not claim to be the only prophet. But an early revelation named him as the only prophet allowed to give commandments "as Moses." This religious authority included economic and political matters, as well as spiritual ones. For example, in the early 1830s, Smith temporarily started a form of religious communism. It was called the United Order. It required Latter Day Saints to give all their property to the church. This property would then be divided among the faithful. He also imagined that the religious government he set up would play a role in the worldwide political organization of the Millennium.

By the mid-1830s, Smith began teaching about three levels of priesthood. These were the Melchizedek, the Aaronic, and the Patriarchal. Each priesthood was a continuation of biblical priesthoods. This happened through family lines or through ordination by biblical figures in visions. When he introduced the Melchizedek Priesthood in 1831, Smith taught that those who received it would be "endowed with power from on high." This would fulfill a desire for greater holiness and authority like the New Testament apostles. This teaching of endowment changed through the 1830s. By 1842, the Nauvoo endowment included a detailed ceremony. It had elements similar to Freemasonry and Jewish Kabbalah. Although the endowment was given to women in 1843, Smith never clarified if women could hold priesthood offices.

Smith taught that the High Priesthood's heavenly power included the sealing powers of Elijah. This allowed High Priests to perform ceremonies that would last after death. For example, this power allowed proxy baptisms for the dead. It also allowed marriages that would last into eternity. Elijah's sealing powers also allowed the second anointing. This, Smith said, sealed married couples to their exaltation.

Smith taught that God appointed only one person on Earth at a time to have this sealing power. In this case, it was Smith. According to Smith, men and women needed to be sealed to each other in this new and everlasting covenant. This was also called "celestial marriage." It was needed to be exalted in heaven after death. Such celestial marriage, passed down through generations, could reunite families in the afterlife.

Plural marriage, or marrying multiple wives, was Smith's "most famous innovation." Once Smith introduced it, it became part of his "Abrahamic project." Smith taught that the solution to humanity's problems was accepting God's divine order. This was a "fusion of ecclesiastical and civic authority."

Smith also taught that the highest level of exaltation could be reached through "plural marriage." This was the ultimate form of the New and Everlasting Covenant. Plural marriage, Smith said, allowed a person to go beyond the angelic state and become a god. It would speed up the growth of one's heavenly kingdom. In Smith's beliefs about God having a body and humans becoming gods, plural marriage was a way for people to overcome the idea that the physical body was sinful. Instead, they could see their physical joy as sacred.

Political Views

When campaigning for President in 1844, Smith shared his political views. Smith believed the U.S. Constitution, especially the Bill of Rights, was inspired by God. He called it "the Saints' best and perhaps only defense." He thought a strong central government was key for the nation. He also thought democracy was better than tyranny. But he also taught that a religious monarchy was the ideal government.

In foreign affairs, Smith supported expansion. He saw it as brotherhood. He imagined expanding the U.S. with permission from Native peoples. He also thought other countries might ask to join. Smith wanted Texas to join the Union. He claimed the Oregon country. He also hoped Canada and Mexico would someday join the United States.

To protect U.S. business and farming, Smith favored high taxes on imports. He also wanted a publicly-owned national bank. This bank would have elected officers. It would print money but "never issue any more bills than the amount of capital stock in her vaults and the interest."

Smith was against putting people in prison for debt. He also opposed prison as a punishment for most crimes (except murder). He suggested ending military courts for deserters. He encouraged people to ask state leaders to pardon all convicts. He thought courts should sentence convicts to work on public projects, like building roads. He argued that providing education would make prisons unnecessary. He also supported capital punishment for public officials who failed to help people whose rights were violated.

Smith said he would help fulfill Nebuchadnezzar's statue vision in the Book of Daniel. This vision said that secular government would be destroyed without bloodshed. It would be replaced with a "theodemocratic" Kingdom of God. Smith taught that this kingdom would be governed by religious principles. But it would also be multi-religious and democratic, as long as people chose wisely.

Slavery and Race

Smith had different views on slavery. At first, he was against it. But in the mid-1830s, when Mormons settled in Missouri (a slave state), he wrote an essay that supported slavery. Then in the early 1840s, after Mormons were forced out of Missouri, he again opposed slavery. During his 1844 presidential campaign, he suggested the federal government end slavery by 1850. This would be done by paying slave owners.

However, historian Donna Hills notes that Smith's "feelings were complex." He did not support black self-government. He also opposed interracial marriage. Smith welcomed black Americans, both enslaved and free, into church membership. But he told his followers not to baptize enslaved people without their owners' permission. He once said that black people "came into the world as slaves." But he also said this was a temporary situation, not a permanent trait. He believed black Americans could be educated as well as white Americans.

Smith and other early Mormons believed racial division was temporary. They thought it was a separation of one human family. They saw Smith's religious movement as a way to restore humanity to its original relationship. However, they imagined this unity as "white universalism." This meant people of color would become like white people. They would "overcome the legacy of spiritual inferiority" that Smith and his followers believed people of color were born into.

See also

In Spanish: Joseph Smith para niños

In Spanish: Joseph Smith para niños

- 1844 United States presidential election[[[Category:Presidents of the Church (LDS Church)]]

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |