Treaty of Tripoli facts for kids

| Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary (Ottoman Empire) | |

|---|---|

| Type | "Treaty of perpetual peace and friendship" |

| Signed | November 4, 1796 |

| Location | Tripoli |

| Effective | June 10, 1797 |

| Parties |

|

| Language | Arabic (original), English |

The Treaty of Tripoli was an important agreement signed in 1796. It was the first treaty between the United States and Tripoli (which is now Libya). The main goal of this treaty was to protect American ships and trade in the Mediterranean Sea. It aimed to stop attacks from local Barbary pirates.

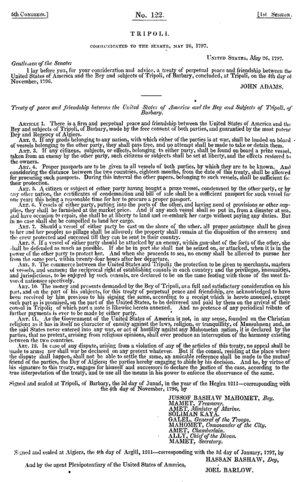

Joel Barlow, an American diplomat, wrote the treaty. It was signed in Tripoli on November 4, 1796. Then, it was confirmed in Algiers on January 3, 1797. The United States Senate approved the treaty on June 7, 1797. It became official on June 10, 1797, when President John Adams signed it.

However, Tripoli later broke the treaty. This led to a conflict called the First Barbary War. A new agreement, the Treaty of Peace and Amity, was signed in 1805.

The Treaty of Tripoli is often talked about when discussing the role of religion in the U.S. government. This is because Article 11 of the English version says: "the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion."

Contents

Stopping the Barbary Pirates

For about 300 years, ships in the Mediterranean Sea faced danger. Muslim states along the Barbary Coast in North Africa attacked them. These states included Tripoli, Algiers, Morocco, and Tunis. They used privateering, which was like government-approved piracy.

Pirates would capture people and either demand money for their return or force them into slavery. Life for these captives was often very hard. Many did not survive.

Before the American Revolution (1775–1783), British warships protected American colonies. Treaties also helped keep them safe from the Barbary pirates. After the Revolution, the United States became independent. It signed the Treaty of Paris (1783). Now, the U.S. had to protect its own ships.

In 1785, Algerian pirates captured two American ships. The people on board were forced into slavery. The U.S. had no strong navy at the time. So, it had to pay money and goods to the Barbary nations. This was to keep its ships safe and free its citizens. An American consul, William Eaton, explained it this way: "The Christians who would be on good terms with them must fight well or pay well."

The U.S. signed a series of "peace treaties" with these nations. These are known as the Barbary treaties. Treaties were made with Morocco (1786), Algiers (1795), Tripoli (1797), and Tunis (1797). Joel Barlow was a key American diplomat. He worked on the text of many of these treaties, including the Treaty of Tripoli.

Signing and Approving the Treaty

George Washington, the first U.S. President, chose David Humphreys to negotiate with the Barbary powers. Humphreys then appointed Joel Barlow and Joseph Donaldson to work on the "Treaty of Peace and Friendship."

The treaty was signed in Tripoli on November 4, 1796. It was confirmed in Algiers on January 3, 1797. Humphreys approved it in Lisbon on February 10, 1797.

The official treaty was written in Arabic. Joel Barlow translated it into English. The United States approved this English version on June 10, 1797.

The treaty traveled for seven months before reaching the United States. It was signed by officials at each stop. There is no record of any big discussions about the treaty when it was approved. President John Adams officially signed the document.

He stated that he had "seen and considered the said Treaty." He then said that with the Senate's approval, he would "accept, ratify, and confirm the same." He ordered that the treaty be made public. He also told all U.S. officials and citizens to "faithfully to observe and fulfill the said Treaty."

Official records show that the entire treaty was read aloud in the Senate. Copies were given to every Senator. A committee looked at the treaty and suggested it be approved. On June 7, 1797, 23 out of 32 Senators voted. They all agreed to approve the treaty.

Payments were part of the treaty. Some goods and money were sent even before the U.S. saw the treaty. However, the Pasha of Tripoli said it was not enough. An additional $18,000 had to be paid later. This payment was made by American Consul James Leander Cathcart in 1799. Only after these final goods were delivered did the Pasha of Tripoli accept the treaty as official.

What is Article 11?

Article 11 of the treaty has caused a lot of discussion. It is often used in talks about the separation of church and state in the U.S. Some people say that Article 11 was not in the original Arabic version of the treaty. However, the English text, which included Article 11, was approved by the U.S. Senate.

Article 11 was meant to show that the United States was a country not based on religion. It wanted to assure the Muslim leaders that this agreement was not like past conflicts with Christian nations, such as the Crusades.

Article 11 states: "Art. 11. As the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion; as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility, of Mussulmen (Muslims); and as the said States never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan (Mohammedan) nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries."

Professor Frank Lambert explains that Article 11 aimed to calm the fears of the Muslim state. It made it clear that religion would not control how the treaty was understood. He says that the Founding Fathers wanted religious freedom for everyone. They made sure that the U.S. would not be an official Christian country.

The treaty was printed in newspapers. There was not much public disagreement about it at the time.

Later Disagreements about Article 11

Years later, some people disagreed with Article 11. James McHenry, who was the Secretary of War, said he protested the language of Article 11 before it was approved. He felt it was wrong to state that the U.S. government was not founded on the Christian religion.

Understanding the Translation

People have questioned Joel Barlow's translation of the Treaty of Tripoli. They have debated if Article 11 in the English version matches anything similar in the Arabic version.

In 1931, Hunter Miller studied U.S. treaties. He said that Barlow's translation was "at best a poor attempt" of the Arabic text. He also claimed that "Article 11... does not exist at all" in the Arabic version.

Miller found that the Arabic text between Articles 10 and 12 was a letter from the Dey of Algiers to the Pasha of Tripoli. He called it "crude and flamboyant and withal quite unimportant." He found it a mystery how this letter became Article 11 in Barlow's translation.

However, Miller also noted that Barlow's translation was the one given to the Senate. It is the English text that has always been considered the official treaty in the United States. The U.S. Senate approved this version unanimously in 1797.

The Barbary Wars

In 1801, Yusuf Karamanli, the Pasha of Tripoli, broke the treaty. He demanded more payments from the U.S. President Thomas Jefferson refused to pay. This led to the First Barbary War.

After several battles, Tripoli finally agreed to peace terms. Tobias Lear negotiated a new "Treaty of Peace and Amity" in 1805. This new agreement included a payment of $60,000. This money was for the release of American prisoners from the USS Philadelphia and other merchant ships.

By 1807, Algiers started capturing U.S. ships again. The U.S. was busy with events leading up to the War of 1812. So, it could not respond until 1815. This led to the Second Barbary War. These wars (1800–1815) finally ended the conflicts with the Barbary states.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |