Jesuit Missions amongst the Huron facts for kids

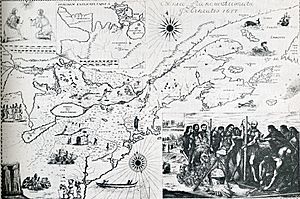

Between 1634 and 1655, Jesuit missionaries came to New France, a French colony along the Saint Lawrence River. They wanted to live with and teach Christianity to the local Huron people. This was a challenging time for the Jesuits. In other places, like Latin America, many people were more open to Christianity because of violence and changes happening there. But in New France, the French government didn't have much power, and there were few French settlements. This made it much harder for the Jesuits to convert the Huron.

Even so, these French missionary settlements were very important. They helped keep good connections in politics, trade, and war between the French and the Huron. The contact between these two groups changed their ways of life, social customs, cultural beliefs, and spiritual practices. The French Jesuits and the Huron had to find ways to get along despite their different beliefs and ways of life.

The Huron lived simple lives. Before meeting the French, they believed their way of life was as good as any other. The Huron traded with the French and other tribes. They exchanged food for European tools and other supplies, which became very important for their survival. The Huron mainly farmed in one place, which the French liked. The French believed that farming and making land productive was a sign of being civilized.

Huron women mostly worked with crops like maize. They planted, cared for, and harvested these crops. Entire villages would move when the soil in one area was used up after a few years. Women also gathered plants and berries, cooked, and made clothes and baskets. However, women did not join the autumn hunts. Men cleared fields, hunted deer, fished, and built their large multi-family longhouses. Men were also in charge of defending the village and fighting during wartime. For example, the Iroquois and the Huron often fought each other. Revenge was a main reason the Huron went to war, but they only decided to fight after long discussions.

The Huron government was very different from European systems. One big difference was that individuals belonged to a family line traced through the mother. Also, Huron people would discuss an issue together until everyone agreed. Their government was based on family groups, and each group had two leaders: a civil leader and a war chief. Huron law focused on four main areas: murder, theft, witchcraft (which both men and women could be accused of), and treason. The Huron did not have a religion like Europeans. Instead, they believed that everything, even man-made things, had souls and lived forever. Dreams and visions were a big part of Huron religion and influenced almost all major decisions.

Contents

Jesuit Conversion Methods

The Jesuit missionaries who came to New France in the 1600s wanted to convert native peoples like the Huron to Christianity. They also aimed to teach them European values. Jesuit leaders thought that if they created European ways of life and social structures, conversion would be easier. They believed that a European lifestyle was the basis for understanding Christian spirituality correctly.

Compared to other native groups in the region, like the hunter-gatherer Innu or Mi’kmaq peoples, the Huron already fit fairly well with the Jesuits’ ideas of stable societies. For example, the Huron had semi-permanent settlements and actively farmed, with maize as their main crop. Still, the Jesuits often found it hard to understand the Huron culture. Their efforts to change Huron religion and society often met with strong resistance.

War and fighting between tribes, however, sometimes made people more open to Christianity. This increased the Jesuits' chances of successful conversion. Yet, natives were also converted in other ways. Father Paul Le Jeune suggested using fear to convert natives. For instance, he showed them scary pictures of Hell. He also used their own fears, like losing a child, to create frightening thoughts. This was meant to make the natives think about their own lives and salvation.

Finding Common Ground

Jesuits often used existing native customs and social structures to enter and settle in villages. This helped them convert the people there. So, missionaries often mixed parts of Christian practice with certain elements of Huron culture. For example, missionaries carefully studied native languages. They spoke to the Huron about Christianity in ways the Huron could understand. They translated hymns, prayers like the Pater Noster, and other religious texts into the Huron language. They would then say these in front of large groups. The book De Religione was written entirely in the Huron language in the 1600s. This book was meant to guide the Huron in Christianity. It covered Christian practices like baptism, talked about different types of souls, Christian ideas about the afterlife, and even why the Jesuits were doing missionary work.

The Jesuits wanted the Huron to become a type of Catholic that was very strict. This was because of decades of violent conflict in France. They could be very against non-Catholic beliefs. This Catholicism demanded a full commitment from new converts. This meant the Huron sometimes had to choose between their Christian faith and their traditional spiritual beliefs, family structures, and community ties.

At first, many Huron were interested in the Jesuits’ stories about the universe's origin and Jesus Christ's life and teachings. Some were even baptized. Others were curious but the Jesuits stopped them from being baptized. This was because the Jesuits worried these Huron were mixing traditional practices with Christian ideas in a dangerous way. Finally, a group of traditionalists preferred Huron ways of talking things out and finding agreement. They were worried by the Jesuits’ forceful preaching and conversion methods. They feared that converts would break all their ritual, family, and community ties. So, they began to actively oppose the missionary program.

Christianity and Huron Society

The disagreements between Christian converts and traditionalists greatly weakened the Huron confederacy in the 1640s. The Jesuits insisted that Christianity and traditional spirituality were not compatible. Because of this, Huron Christians often distanced themselves from their people's traditional practices. This threatened the ties that once held communities together. Converts refused to join shared feasts. Christian women rejected traditional suitors. They carefully followed Catholic fasts. They also kept Christian remains out of the Feast of the Dead. This was an important ritual of digging up and reburying bones together. The Jesuit missionary Jean de Brébeuf described this event in The Jesuit Relations, explaining that:

Many of them think we have two souls, both of them being divisible and material, and yet both reasonable. One of them separates itself from the body at death yet remains in the cemetery until the Feast of the Dead, after which it either changes into a dove, or according to a common belief, it goes away at once to the village of souls. The other is more attached to the body and, in a sense, provides information to the corpse. It remains in the grave after the feast and never leaves, unless someone bears it again as a child.

The Feast combined Huron spiritual ideas about souls and a community's connection to life, death, and new life. When Christians refused to take part in important community rituals like this, it directly threatened the Huron's traditional spiritual and physical unity.

Religion and Sickness

The Huron population suffered greatly from violence, people being spread out, and waves of Old World diseases. These included smallpox, influenza, and measles. Native populations had no natural protection against these illnesses. When these epidemics hit, many Huron blamed the Jesuits.

In terms of religion, the Jesuits were competing with native spiritual leaders. The Jesuits often presented themselves as shamans who could affect people's health through prayer. Aboriginal people had mixed feelings about shamanistic power. They believed shamans could do both good and bad. As a result, the Huron easily blamed the Jesuits for their good fortune as well as their problems with disease, sickness, and death.

Many Huron were especially suspicious of baptism. The Jesuits often secretly baptized sick and dying babies. They believed these children would go to heaven since they hadn't had time to sin. Similarly, baptisms at deathbeds became common during these widespread diseases. But the Huron saw baptism as a bad kind of magic that marked someone for death. Resistance to the Jesuit missions grew as the Huron faced repeated blows to their population and their political, social, cultural, and religious heritage.

Ideas of Martyrdom

The Jesuits first thought it would be easy to convert native people. They believed these people lacked religion and would eagerly accept Catholicism. But they found this was much harder than it seemed. The harsh Canadian environment and the threat of violence from native peoples made things worse. The Jesuits began to see their difficulties as a literal preparation for their eventual martyrdom. They started talking about themselves differently. They went from being successful missionaries to seeing themselves as living martyrs. They felt despised by the very people they had come to help. By the 1640s, the Jesuits expected violence. They believed they were meant to suffer and die. They hoped for spiritual triumph by connecting their deaths to the suffering of Christ. Father Paul Le Jeune, the first Jesuit superior of the New France mission, said:

Considering the glory that redounds to God from the constancy of the martyrs, with whose blood all the rest of the earth has been so lately drenched, it would be a sort of curse if this quarter of the world should not participate in the happiness of having contributed to the splendour of this glory.

Similarly, shortly before his own violent death, the missionary Jean de Brébeuf wrote:

I make a vow to you never to fail, on my side, in the grace of martyrdom, if by your infinite mercy you offer it to me someday, to me, your unworthy servant… my beloved Jesus, I offer to you from to-day… my blood, my body, and my life; so that I might die only for you.

Brébeuf was violently killed by the Iroquois during a destructive attack on the Christian Huron settlement of St. Louis in 1649. He was later made a saint in the 1900s. So, the contact between the Huron and Jesuits brought big changes to the spiritual, political, cultural, and religious lives of both native peoples and Europeans in North America.

Decline of the Huron

In the summer of 1639, a smallpox epidemic hit the native peoples in the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes regions. The disease reached the Huron tribes through traders returning from Québec. It stayed in the region through the winter. After the epidemic, the Huron population was reduced to about 9,000 people. This was half of what it had been before 1634.

The Huron people faced many challenges in the 1630s and 1640s. Many diseases, relying on others for trade, and attacks from the Iroquois tribe all caused the Huron population to shrink and divided their society. These reasons also led many natives to convert to Catholicism. In the late 1640s, villages that were discouraged and without leaders converted in large numbers. However, the Jesuit success was short-lived. The Iroquois destroyed the Huron nations in the spring of 1649.

In the 1640s, the Huron managed to trade the same amount of furs to the French, even after their population was cut in half. The changes needed to keep up this trade were very hard on their society. Traders were always traveling between Huronia and the St. Lawrence. Many were captured or killed by the Iroquois, especially between 1641 and 1644. Also, with so many men away, Huron settlements were more open to Iroquois attacks.

War with the Iroquois

Native warfare became more deadly in the 1600s. This was due to the use of firearms and increasing pressures from epidemics and European trade. However, being able to kill more efficiently might not have been the main reason the Iroquois destroyed the Huron. For unclear reasons, the Iroquois changed their military goal from capturing prisoners to destroying the entire Huron people. Yet, there was some disagreement within the Iroquois. One group wanted to make peace with the French, while the other wanted war. When the group wanting war won, fighting between the Iroquois and their Huron enemy increased.

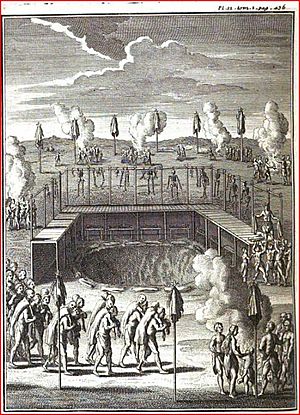

This change in overall strategy led to changes in Iroquois tactics. The old way of surrounding a Huron village to challenge its defenders to come out and fight changed. Instead, they used surprise attacks at dawn, followed by stealing, burning, and long lines of captives carrying away stolen goods. Also, native attacks in the past were quick. The raiding party would leave after causing the planned damage. In the late 1640s, however, Iroquois tactics changed. They kept hunting down those who had fled during and after battles.

In 1645, the Huron mission town of St. Joseph was attacked. But for the next two years, there was little violence between the Huron and Iroquois. This was because of a peace agreement between the Iroquois and the French and their native allies. The unstable peace ended in the summer of 1647. A diplomatic mission led by Jesuit Father Isaac Jogues and Jean de Lalande to Mohawk territory (one of the five Iroquois nations) was accused of being traitors and using bad magic. Jogues and La Lande were beaten when they arrived and killed the next day. Some of the Huron who had gone with Jogues were able to return to Trois-Rivières. They told the French what had happened.

Between 1648 and 1649, Huron settlements with Jesuits, like the towns of St. Joseph under Father Antoine Daniel, the villages of St. Ignace and St. Louis, and the French fort of Ste. Marie, were repeatedly attacked by the Iroquois. The Iroquois killed everyone they found. This was a final blow to the already weak Huron population. Those who were not killed scattered. For example, women and children were often adopted into new societies and cultures. By the end of 1649, however, the Huron as a distinct people, with their own political, cultural, religious, or even geographical identity, no longer existed. Jesuits were among those captured, tortured, and killed in these attacks. From the missionaries' point of view, individuals like Jean de Brébeuf died as martyrs.

Aftermath

"Weakened, divided, and discouraged, the Huron nations collapsed as a result of the strong attacks from the Iroquois in 1649." While the Iroquois failed to take the French fort, Ste. Marie, they had won overall. The Huron were divided in politics, society, culture, and religion. These violent attacks delivered a final blow to their unity. Terrified of more attacks, the survivors began to flee. By the end of March, fifteen Huron towns had been abandoned. Many Huron joined the Iroquois, while others became part of nearby tribes. One group of Huron people escaped to Île St. Joseph. But with their food supplies destroyed, they soon faced starvation. Those who left the island to find food risked meeting Iroquois raiders. These raiders hunted down the hunters with a fierceness that surprised the Jesuits. A small group of Catholic Huron followed the Jesuits back to Québec City.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |