George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Lord Baltimore

|

|

|---|---|

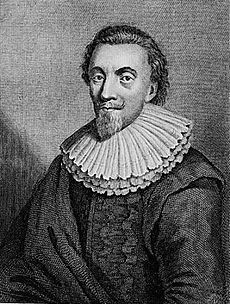

George Calvert, 1st Lord Baltimore, by John Alfred Vinter

|

|

| Secretary of State | |

| In office 1618–1625 |

|

| Proprietor of the Avalon Colony (Newfoundland) | |

| In office 1620–1632 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1580 Kiplin, North Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 15 April 1632 (aged 52–53) Lincoln's Inn Fields, London, England |

| Spouses | Anne Mynne (m. 1604) Joane |

| Children | 12, including: |

| Signature |  |

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore (1580 – 15 April 1632), was an English politician and colonial leader. He served as a member of Parliament and later as Secretary of State for King James I. He lost some political power after supporting a marriage alliance between Prince Charles and the Spanish royal family, which did not happen.

In 1625, he resigned most of his political roles and openly declared his Catholic faith. He was then given the title of Baron Baltimore. Calvert was very interested in setting up English colonies in the Americas. At first, he wanted to make money, but later he also wanted to create a safe place for persecuted Catholics from England and Ireland.

He became the owner of Avalon, the first lasting English settlement on the island of Newfoundland (in modern Canada). The cold weather and hardships for the settlers made him look for a warmer place further south. He asked the king for a new charter to settle the area that would become Maryland. Calvert died just five weeks before this new charter was officially approved. His son, Cecil, took over the Maryland colony project. His second son, Leonard Calvert, became Maryland's first colonial governor.

Contents

Family and Early Life

Not much is known about the early family history of the Calverts from Yorkshire. When George Calvert was knighted, it was said his family came from Flanders (now part of Belgium). George's father, Leonard Calvert, was a country gentleman. He was wealthy enough to marry Alicia Crossland, who came from a noble family. They lived on an estate near Kiplin Hall in Yorkshire, where George was born in late 1579. His mother, Alicia, died when he was eight. His father then married Grace Crossland, Alicia's cousin.

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the English government controlled religious matters. Laws were passed to make everyone follow the Church of England. These laws, like the Acts of Supremacy, required people to swear loyalty to the Queen and reject the Pope's authority. Anyone who wanted to hold important jobs or go to university had to take this oath.

The Calvert family faced challenges because of these religious laws. George's father, Leonard, was often bothered by authorities. In 1580, he had to promise to attend Church of England services. In 1592, when George was twelve, one of his tutors was accused of teaching from a "popish primer." Leonard and Grace were told to send George and his brother Christopher to a Protestant tutor. They also had to show their children to officials once a month to check on their learning. Leonard also had to agree not to hire any Catholic servants. He was also forced to buy an English Bible for his home.

In 1593, records show that Grace Calvert was held by an official who hunted down Catholics. In 1604, she was described as "non-communicant at Easter," meaning she did not take communion in the Church of England.

George Calvert went to Trinity College at Oxford University in 1593 or 1594. He studied foreign languages and earned a bachelor's degree in 1597. Since the loyalty oath was required after age sixteen, he likely took it at Oxford. After Oxford, he moved to London in 1598. He studied law at Lincoln's Inn for three years.

Marriage and Family Life

In November 1604, George Calvert married Anne Mynne. Their wedding was a Protestant ceremony at St Peter's Church in Cornhill, London. All of their children, including their eldest son Cecil (born in 1605–06), were baptized in the Church of England. When Anne died on August 8, 1622, she was buried in Calvert's local Protestant church.

Calvert had twelve children in total. These included Cecil, who became the 2nd Baron Baltimore, and Leonard Calvert, who was the first governor of Maryland.

Rising in Politics

Calvert named his son "Cecilius" after Sir Robert Cecil, a powerful advisor to Queen Elizabeth. Calvert met Cecil during a trip to Europe between 1601 and 1603. After this, Calvert became known for his knowledge of foreign affairs. He joined Cecil's service, who was a key person in helping King James VI of Scotland become King James I of England in 1603.

King James rewarded Robert Cecil by making him a Privy Councillor and Secretary of State. Cecil became the Earl of Salisbury in 1605 and Lord High Treasurer in 1608. As Cecil gained power, Calvert also rose with him. Calvert's language skills, legal training, and careful nature made him very valuable to Cecil. Calvert gained several small jobs and honors. In 1605, he received an honorary master's degree from Oxford, showing his growing importance.

In 1606, King James made Calvert "clerk of the Crown" in Ireland. In 1609, he became a "clerk of the Signet office," which meant he prepared documents for the king's signature. This brought him close to the king. Calvert also served in Parliament, representing the town of Bossiney. In 1610, he was appointed a "clerk of the Privy Council." All these jobs required him to take the oath of allegiance.

With Robert Cecil's help, George Calvert became a trusted advisor to King James. In 1610 and 1611, Calvert went on missions to Europe for the King. He visited embassies in Paris and Holland. He also acted as an ambassador to the French Royal Court during the coronation of King Louis XIII in 1610. People said Calvert was very discreet and made a good impression. In 1615, James sent him to the German Electorate of the Palatinate. Calvert had to tell the Elector, Frederick V, Elector Palatine, that the King was unhappy. Frederick had married James's daughter Elizabeth of Bohemia in 1613.

In 1613, the King asked Calvert to investigate complaints from Roman Catholics in Ireland. The group spent almost four months there. Their report, partly written by Calvert, suggested that religious rules should be followed more strictly in Ireland. It also recommended closing Catholic schools. In 1616, James gave Calvert the manor of Danby Wiske in Yorkshire. This connected him with Sir Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, who became his close friend. Calvert was now rich enough to buy the Kiplin Hall estate in his home area. Today, University of Maryland has a research center there, and the main building is a museum. In 1617, Calvert was knighted, becoming Sir George Calvert.

In 1619, Calvert reached a high point in his career. James appointed him as one of the two main secretaries of state. This happened after the previous secretary was dismissed due to scandals. Calvert's appointment surprised many people. He believed he owed his promotion to the king's favorite, George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (later the first Duke of Buckingham). Calvert sent Villiers a valuable jewel as thanks. Villiers returned the jewel, saying he had nothing to do with the appointment. Calvert's personal wealth grew even more. He was also made a "commissioner of the treasury" and received a large pension.

Serving as Secretary of State

In Parliament, a big political problem arose. The king wanted his son, Charles, Prince of Wales, to marry a Spanish princess. This was part of a plan to form an alliance with the powerful Spanish royal family. In the Parliament of 1621, Calvert had to argue for this "Spanish Match." Most members of Parliament were against it. They worried about more Catholic influence in England. Because he supported Spain and wanted to relax laws against Catholics, Calvert became unpopular with many in Parliament. He also faced personal difficulties. His wife died on August 8, 1622, leaving him to raise ten children alone.

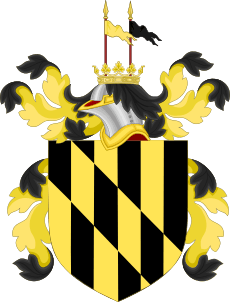

In 1623, King James rewarded Calvert for his loyalty. He gave him a large estate in County Longford, Ireland. This estate was known as the "Manor of Baltimore." The name Baltimore comes from the Irish words meaning "town of the big house." Calvert became less important at court as the Prince of Wales and George Villiers took more control from the aging King James. Without asking Calvert, the prince and duke went to Spain to arrange the marriage themselves. This trip failed badly. Instead of an alliance, it led to hostility between the two countries and soon to war. Buckingham then changed policy, ending the Spanish treaties and seeking a French marriage for the Prince of Wales.

Leaving Office and Becoming Catholic

As the main person in Parliament who supported the failed Spanish policy, Calvert was no longer useful to the English Royal Court. By February 1624, his duties were limited to calming the Spanish ambassador. He was even criticized for supposedly delaying diplomatic letters. Calvert accepted what was happening. He used his poor health as an excuse and began to sell his position. He finally resigned as Secretary of State in February 1625.

Calvert's departure from office was not a disgrace. The King, to whom Calvert had always been loyal, kept him on the Privy Council. He also made him Baron Baltimore, named after one of his Irish estates. Right after Calvert resigned, he became a Roman Catholic.

The reasons for Calvert's conversion were complex. Some believed he had been secretly Catholic for a long time. Others thought he converted because he lost his job and was unhappy. George Abbot, the Archbishop of Canterbury, said Calvert became Catholic out of "desperation." However, it seems most likely Calvert converted in late 1624. A priest reported in Rome that he had converted two Privy Councillors to Catholicism, and one of them was certainly Calvert. Calvert later worked with this priest on a plan for a Catholic mission in his new colony in Newfoundland.

When King James I died in March 1625, his son Charles I became king. Charles I kept Calvert's title as Baron Baltimore but did not keep him on the Privy Council. Calvert then focused on his Irish estates and his investments overseas. He was not completely forgotten at court. After Buckingham's wars against Spain and France failed, he called Baltimore back to court. For a while, Buckingham thought about using Baltimore in peace talks with Spain. Although nothing came of this, Baltimore renewed his rights over silk-import duties. He also got King Charles's approval for his plan in the "New Found Land."

The Avalon Colony in Newfoundland

Calvert had long been interested in exploring and settling the New World. He invested in the Virginia Company in 1609 and the East India Company in 1614. In 1620, Calvert bought land in Newfoundland from Sir William Vaughan. Vaughan was a Welsh writer and investor who had failed to start a colony on the large island off eastern North America. Calvert named his area Avalon, after a legendary place where Christianity was said to have been brought to ancient Britain. This plantation was on what is now called the Avalon Peninsula. It included the fishing station at "Ferryland." Calvert likely planned a fishing business there.

Calvert sent Captain Edward Wynne and a group of Welsh colonists to Ferryland. They arrived in August 1621 and began building a settlement. Wynne sent good reports about the fishing potential. He also mentioned that the area could produce salt, hemp, flax, tar, iron, timber, and hops. Wynne praised the climate, saying it was "better and not so cold as England." He believed the colony would support itself within a year. Other reports agreed. Captain Daniel Powell, who brought more settlers, said the land was very good. However, he also warned that Ferryland was "the coldest harbour in the land." Wynne and his men built a large house and improved the harbor. To protect against French warships, Calvert hired a pirate named John Nutt.

The settlement seemed to be doing so well that in January 1623, Calvert received a grant from King James for all of Newfoundland. However, this grant was soon reduced to only the southeastern Avalon peninsula. This was because other English colonists had competing claims. The final charter made the province a "county palatinate," officially called the "Province of Avalon," under Calvert's personal rule.

After resigning as Secretary of State in 1625, the new Baron Baltimore planned to visit his colony. He wrote in March, "I intend shortly... a journey for Newfoundland to visit a plantation which I began there." His plans were delayed by the death of King James I. They were also delayed by King Charles I's crackdown on Catholics. The new King required all privy councillors to take oaths of supremacy and allegiance. Since Baltimore was Catholic, he refused and had to leave that important office. Because of the new religious and political situation, and perhaps to escape a serious outbreak of plague in England, Baltimore moved to his estates in Ireland. His expedition to Newfoundland sailed without him in late May 1625. Sir Arthur Aston became the new governor of Avalon.

Baltimore had recently remarried a woman named Joane (also called Jane).

From his conversion in 1625, Baltimore made sure to provide for the religious needs of his colonists, both Catholic and Protestant. He had asked a priest named Simon Stock to send priests for the 1625 expedition. However, Stock's priests arrived in England after Aston had already sailed. Stock had big plans for the colony. He believed the Newfoundland settlement could help convert native people in the New World.

Baltimore in Avalon

Baltimore was determined to visit his colony himself. In May 1626, he wrote to his friend Wentworth. He said he needed to go and improve the colony, or he would lose all the money he had spent. He preferred to be seen as foolish for a short trip than to lose everything he had worked for.

Aston and all the Catholic settlers returned to England in late 1626. This did not stop Baltimore. He finally sailed for Newfoundland in 1627. He arrived on July 23 and stayed only two months before returning to England. He brought both Protestant and Catholic settlers with him. He also brought two priests, Thomas Longville and Anthony Pole. Pole stayed in the colony when Baltimore left. The land Baltimore saw was not the paradise some early settlers had described. It was only somewhat productive. The summer climate was mild, but his short visit did not change his plans for the colony.

In 1628, he sailed again for Newfoundland. This time, he brought his second wife, Jane, most of his children, and 40 more settlers. He officially took over as the owner and governor of Avalon. He and his family moved into the house built by Wynne in Ferryland. It was a large house for the time and the only one big enough for religious services for the community.

Religious matters caused problems for Baltimore in "this remote part of the world." He sailed when England was preparing to help the Huguenots (French Protestants) at La Rochelle. He was upset to find that the war with France had spread to Newfoundland. He had to spend most of his time fighting off French attacks on English fishing fleets using his own ships. He wrote that he came to "build, and sett, and sowe, but I am falne to fighting with Frenchmen." His settlers were so successful against the French that they captured several ships. They sent these ships back to England to help with the war. Baltimore was allowed to borrow one of the ships to defend his colony. He also received a share of the prize money.

Baltimore allowed free religious worship in the colony. Catholics worshipped in one part of his house, and Protestants in another. This new arrangement was too much for the local Anglican priest, Erasmus Stourton. After arguments with Baltimore, Stourton was sent back to England. He quickly reported Baltimore's practices to the authorities. He complained that the Catholic priests said mass every Sunday and used all the ceremonies of the Church of Rome. He also claimed Baltimore had a Protestant's son forcibly baptized as a Catholic. The Privy Council investigated Stourton's complaints, but the case was dismissed because Baltimore had powerful friends.

Baltimore became unhappy with conditions in "this wofull country." He wrote to his old friends in England, complaining about his troubles. The final blow was the Newfoundland winter of 1628–29, which lasted until May. Like others before them, the people of Avalon suffered greatly from the cold and lack of food. Nine or ten of Baltimore's group died that winter. At one point, half the settlers were sick, and his house became a hospital. The sea froze, and nothing would grow before May. Baltimore wrote that it was "not terra Christianorum" (not a land for Christians). He told the king, "I have found... by too deare bought experience [that which other men] always concealed from me... that there is a sad face of wynter upon all this land."

Baltimore asked the king for a new charter. He wanted to start another colony in a warmer climate further south. He asked for an area in Virginia where he could grow tobacco. He wrote to his friends Francis Cottington and Thomas Wentworth for support. He admitted that leaving Avalon might make people think he was "giddy and light-minded." The king replied, expressing concern for Baltimore's health. He gently advised him to forget colonial plans and return to England, where he would be treated with respect. The king said, "Men of your condition and breeding are fitter for other employments than the framing of new plantations, which commonly have rugged & laborious beginnings."

Baltimore sent his children home to England in August. By the time the king's letter reached Avalon, he had already left with his wife and servants for Virginia.

Trying to Start a Southern Colony

In late September or October 1629, Baltimore arrived in Jamestown. The Virginians did not welcome him. They suspected he wanted some of their land and strongly disliked Catholicism. They made him take the oaths of supremacy and allegiance, which he refused. So, they ordered him to leave. After only a few weeks, Baltimore left for England to get his new charter. He left his wife and servants behind. In early 1630, he sent a ship to fetch them, but it sank off the Irish coast, and his wife drowned. Baltimore later described himself as "a long time myself a Man of Sorrows."

Baltimore spent the last two years of his life constantly working to get his new charter. However, there were many difficulties. The Virginians, led by William Claiborne, strongly argued against a separate colony in the Chesapeake Bay area. They claimed they had rights to that land. Baltimore was also low on money, having spent most of his fortune. He sometimes had to rely on his friends for help. To make things worse, in the summer of 1630, his household was infected by the plague, but he survived. He wrote, "Blessed be God for it who hath preserved me now from shipwreck, hunger, scurvy and pestilence..."

His health was getting worse, but Baltimore's persistence finally paid off in 1632. The king first offered him a location south of Jamestown. But Baltimore asked the king to reconsider because other investors wanted to settle the new land of Carolina for sugar plantations. Baltimore eventually agreed to new boundaries north of the Potomac River, on both sides of the Chesapeake Bay. The charter was about to be approved when the fifty-two-year-old Baltimore died on April 15, 1632. Five weeks later, on June 20, 1632, the charter for Maryland was officially approved.

Legacy

In his will, written the day before he died, Baltimore asked his friends Wentworth and Cottington to look after his first son, Cecil. Cecil inherited the title of Lord Baltimore and the upcoming grant for Maryland. Baltimore's two colonies in the New World continued under his family's ownership. Avalon, which was a great place for salting and exporting fish, was taken over by Sir David Kirke. Cecil Calvert strongly challenged this, and Avalon was finally absorbed into Newfoundland in 1754. Although Baltimore's Avalon project failed, it helped lay the groundwork for permanent settlements in that part of Newfoundland.

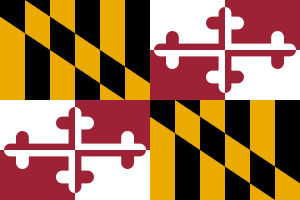

Maryland became an important colony for growing and exporting tobacco in the mid-Atlantic region. For a time, it was also a safe place for Catholic settlers, just as George Calvert had hoped. Under the rule of the Lords Baltimore, thousands of British Catholics moved to Maryland. They established some of the oldest Catholic communities in what later became the United States. However, Catholic rule in Maryland eventually ended when the king took back control of the colony.

One hundred and forty years after its first settlement, Maryland joined twelve other British colonies. They declared their independence from British rule. They also declared the right to freedom of religion for all citizens in the new United States.

The World War II Liberty Ship SS George Calvert was named in his honor.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |