Religion in early Virginia facts for kids

The story of religion in early Virginia starts when the Virginia Colony was founded. This was in 1607, when Anglican church services began in Jamestown. By 1619, the Church of England became the official church of the Colony of Virginia. It was a very important part of life, influencing religion, culture, and politics. But as the 1700s went on, other Protestant groups, called dissenters, started to challenge its power. After the American Revolution, Virginia passed the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786. This law ended government support for the Church of England. It also made it legal for people to practice any religion they wanted, both in public and private.

Contents

How Religion Shaped Early Virginia

After Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492, many European countries started exploring and settling the Americas. This was also a time of big religious changes in Europe, like the Protestant Reformation. In the 1530s, England separated from the Roman Catholic Church. It then formed its own official church, the Church of England.

However, many groups within England, known as English Dissenters, disagreed with the Church of England. They had different ideas about religion. These disagreements often led to conflicts in Europe. These conflicts also affected how colonists interacted in the new lands during the 1600s and 1700s.

In 1570, a group of Spanish Jesuit missionaries tried to start a mission in Virginia. It was called the Ajacán Mission. Most of them were killed by the local people in 1571. After this, no Catholic churches were built in Virginia until after the American Revolution. Still, some old Catholic items found at the Jamestown site make some people wonder if a few early settlers might have secretly been Catholic.

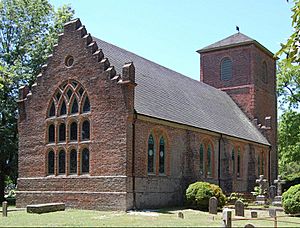

Anglicanism Arrives in Virginia

Anglicanism first came to America with the Roanoke Colony. This colony was in what is now North Carolina. Even though it didn't last long, it's where the first baptisms into the Church of England in North America happened.

Reverend Robert Hunt was an Anglican chaplain. He came with the first English colonists to Virginia in 1607. He passed away by 1608. Richard Buck took over as chaplain until 1624. By the time the Virginia Company of London stopped operating in 1624, England had sent 22 Anglican priests to the colony.

Religious leaders in England felt it was their job to bring Christianity to the Native Americans. They especially wanted to share the beliefs of the Church of England. They thought that Native Americans' spiritual beliefs were "mistaken" because they didn't have a written language.

The English believed that teaching Native Americans to read and write would help them understand Christianity. This was also a way for the government and church to have more control. Reverend Alexander Whitaker was one of the first missionaries. He served from 1611 until his death in 1616. There were plans to build a school for Virginia Indians at Henricus. But these plans were stopped after the Indian Massacre of 1622. It would be another 100 years before such a school was built.

Most of the Powhatan tribes did not fully convert to Christianity until 1791. The only exception was the Nansemond tribe, which converted in 1638.

The Official Church of Virginia

The Church of England became the official church in the colony in 1619. This meant that local taxes helped pay for the church. These taxes also supported local government needs, like roads and helping the poor. The minister's salary was paid this way too.

How Anglican Parishes Worked

Just like in England, the parish became a very important local area. It had as much power as the courts and even the House of Burgesses. The House of Burgesses was part of the Virginia General Assembly.

A typical parish usually had three or four churches. Churches needed to be close enough for people to travel to services. Everyone was expected to attend. As more people moved to Virginia, new parishes were created. The goal was to have a church within six miles (about 10 km) of every home. This made it easy for people to attend services.

A parish was usually led by a rector, who was a priest. A committee of respected community members, called the vestry, governed the parish. There was never a bishop in colonial Virginia. So, the local vestry had a lot of control over the parish. The Anglican priests were supervised by the Bishop of London. By the 1740s, there were about 70 Anglican priests in the colony.

Parishes often had a church farm, called a "glebe". This farm helped support the church financially. Each county court gave tax money to the local vestry. The vestry gave the priest a glebe of 200 or 300 acres (about 0.8 to 1.2 square kilometers). They also provided a house and sometimes animals. The priest received an annual salary of 16,000 pounds of tobacco. They also got 20 shillings for every wedding and funeral. Priests lived simply, and it was hard for them to move up in their careers.

In 1758, a law called the Two Penny Act was passed. This happened after a bad tobacco crop made prices go up. The law allowed clergy to be paid two pence for each pound of tobacco they were owed. The British government canceled this law. This made some colonists angry and led to a famous lawsuit by the clergy for their unpaid wages. This event was called the Parson's Cause.

Other Religions in Virginia

Ministers often complained that colonists were not very interested in Anglican church services. They said people would sleep, whisper, or just stare out windows. Because there weren't many towns, churches had to serve people spread out across the land. There was also a shortage of trained ministers. This made it hard for people to practice their faith outside of their homes. Some ministers encouraged people to be religious at home. They used the Book of Common Prayer for private prayers. This allowed devout Anglicans to have a strong religious life even if they didn't like formal church services. This focus on personal faith also made people feel less need for a bishop or a large church system. It also helped prepare the way for the First Great Awakening. This movement drew people away from the official church.

In 1689, the English Parliament passed the Act of Toleration. This law allowed some Protestant groups, called Nonconformists, to worship freely in England. Similar rules were put in place in Virginia. Baptists, German Lutherans, and Presbyterians paid their own ministers. They also wanted the Anglican church to no longer be the official church. However, by the mid-1700s, Baptists and Presbyterians faced more challenges. Between 1768 and 1774, about half of the Baptist ministers in Virginia were put in jail for preaching.

In the frontier areas, many families had no religious ties. The Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians challenged what they saw as low moral standards. They did not allow such behavior among their members. These groups saw gambling, drinking, and fighting as sinful. They also challenged the idea that men should have total control over women, children, and enslaved people. These religious groups created new rules for behavior. They helped create a new type of male leadership based on Christian ideas, which became common in the 1800s.

Presbyterians in Virginia

Presbyterians were Protestant dissenters. Most of them were Scotch-Irish Americans. Their numbers grew in Virginia between 1740 and 1758, just before the Baptists. The Church of Scotland had adopted Presbyterian ideas in the 1560s. This often led to disagreements with the Church of England.

Where Presbyterians were the main group, they could have power through the official church's vestry. The vestry's members often showed their leadership. For example, Presbyterians held at least nine of the twelve spots on the first vestry of Augusta parish in Staunton, Virginia, which started in 1746.

The First Great Awakening influenced the area in the 1740s. This led to Samuel Davies being sent from Pennsylvania in 1747. He led and ministered to religious dissenters in Hanover County, Virginia. He helped create the first presbytery (a group of Presbyterian churches) in Virginia, called the Presbytery of Hanover. He also shared Christianity with enslaved people, which was unusual at the time. He even influenced a young Patrick Henry, who went with his mother to listen to sermons.

Historians say that Presbyterians were more active. They held frequent services that fit the frontier life of the colony. Presbyterianism grew in western areas where the Anglicans had less influence. These areas included the Piedmont and the valley of Virginia. People who had not been educated, both white and Black, were drawn to their emotional worship. They liked the focus on simple Bible teachings and singing psalms. Presbyterians came from all parts of society. They were involved in slaveholding and managing households in traditional ways. The Presbyterian Church government had few democratic parts. Some local Presbyterian churches, like Briery in Prince Edward County, owned enslaved people. The Briery church bought five enslaved people in 1766. They earned money for church costs by hiring them out to local planters.

Baptists in Virginia

The First Great Awakening and many traveling missionaries helped Baptists grow. By the 1760s, Baptists were attracting Virginians, especially poor white farmers. They offered a new, more democratic religion. Enslaved people were welcome at services, and many became Baptists then.

Baptist services were very emotional. The only main ritual was baptism, which was done by fully immersing adults in water. This was different from the Anglican practice of sprinkling. Baptists disagreed with the common moral standards in the colony. They strictly followed their own high standards of personal behavior. They were concerned about bad conduct, heavy drinking, wasting money, missing services, cursing, and wild parties. Church trials were held often. Members who did not follow the rules were removed.

Historians have discussed how these religious rivalries affected the American Revolution. Baptist farmers brought new ideas of equality. These ideas largely replaced the older, more aristocratic ideas of the Anglican planters. However, both groups supported the Revolution. There was a clear difference between the simple life of the Baptists and the wealthy life of the Anglican planters. The planters controlled local government. Baptist church rules, which the wealthy sometimes mistook for radical ideas, actually helped keep order. As more people moved to Virginia, the county court and the Anglican Church gained more power. The Baptists strongly protested this. The conflict between the "evangelical" (Baptist) and "gentry" (Anglican) styles became very intense. The strength of the evangelical movement's organization helped it gain power outside the usual government structure. The fight for religious freedom happened during the American Revolution. Baptists, working with Anglicans Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, successfully ended the Anglican church's official status.

Methodists in Virginia

Methodism began in the 1700s as a movement within the Anglican church. Methodist missionaries were active in Virginia during the late colonial period. From 1776 to 1815, Methodist Bishop Francis Asbury traveled 42 times to visit Methodist groups in western Virginia.

Methodists encouraged an end to slavery. They welcomed both free Black people and enslaved people to be active in their churches. Like the Baptists, Methodists converted many enslaved and free Black people. They offered them a warmer welcome than the Anglican Church did. Some Black individuals were chosen as preachers. During the Revolutionary War, about 700 enslaved Methodists sought freedom by joining the British side. The British moved them and other Black Loyalists to their colony of Nova Scotia. In 1791, Britain helped some Black Loyalists move to Sierra Leone in Africa. This happened because they faced racism from other Loyalists and had problems with the climate and land they were given.

After the Revolution, in the 1780s, traveling Methodist preachers carried anti-slavery petitions. They rode throughout Virginia, asking for an end to slavery. They also encouraged slaveholders to free their enslaved people. So many slaveholders did this that the number of free Black people in Virginia greatly increased. In the first 20 years after the Revolutionary War, free Black people went from less than one percent to 7.3 percent of the population.

At the same time, other petitions were passed around that supported slavery. These petitions were presented to the Assembly and debated. But no laws were passed. After 1800, religious opposition to slavery slowly decreased. This was because slavery became more important to the economy after the invention of the cotton gin.

Religious Freedom and Change

At the start of the American Revolution, Anglican Patriots realized they needed support from other religious groups. They agreed to most of the dissenters' demands in exchange for their help in the war. During the war, 24 (20%) of the 124 Anglican ministers supported Britain. They usually left the country, and Britain paid them for some of their financial losses.

After America won the war, the Anglican church wanted the government to support religion again. But this effort failed. Non-Anglicans supported Thomas Jefferson's "Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom." This bill became law in 1786. With freedom of religion as the new main idea, the Church of England was no longer the official church in Virginia. Worship continued as usual, but the local vestry no longer used tax money or handled local government tasks like helping the poor. The Right Reverend James Madison (1749–1812), a cousin of Patriot James Madison, became the first Episcopal Bishop of Virginia in 1790. He slowly helped rebuild the church under the new freedom of belief and worship.

At the same time, the new law opened the door for other religions. The first Jewish synagogue in Virginia, Kahal Kadosh Beth Shalome, was founded in 1789. Construction on the Church of Saint Mary in Alexandria began in 1795. This became the first Catholic church in Virginia since the failed Jesuit Mission in the 1500s.

The idea of separating church and state was later included in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. This amendment was approved in December 1791.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |