Rehabilitation trial of Joan of Arc facts for kids

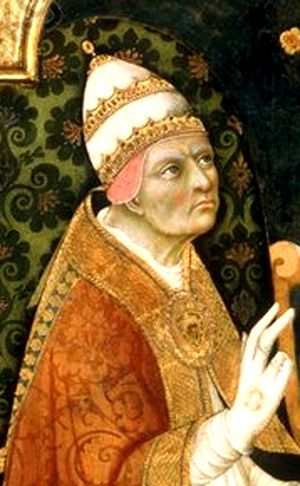

After Joan of Arc was found guilty in 1431, her case was looked at again many years later. This happened in the 1450s because Joan's family, including her mother Isabelle Romée and her brothers Jean and Pierre, asked for it. Pope Callixtus III gave permission for this new investigation.

The main goal of this second trial was to see if Joan's first trial and its decision were fair and followed the rules of the Church. The investigations began in 1452. A formal request for a new trial was made in November 1455. Finally, on July 7, 1456, the first trial was declared invalid. This was because of unfair methods, lies, and cheating. All the charges against Joan were removed.

Contents

Why Joan's Case Was Reopened

Joan of Arc was executed in Rouen on May 30, 1431, for being a heretic. This caused a big problem for King Charles VII. Joan had played a huge part in helping him become the King of France. If she was a heretic, it suggested that his crowning was not proper.

A full review of Joan's trial could not happen before 1449. This was because the city of Rouen, where all the trial papers were kept, was still controlled by the English. King Charles VII did not take back Rouen until November 1449.

Early Attempts to Clear Her Name

Bouillé's First Look in 1450

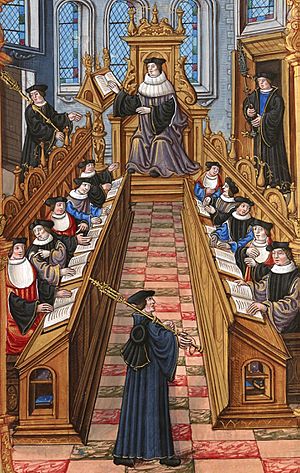

On February 15, 1450, King Charles VII ordered a church leader named Guillaume Bouillé to start an investigation. Bouillé was a scholar from the University of Paris. His job was to find out what went wrong in Joan's first trial.

This was a tricky task. Some people from the University of Paris had helped decide Joan's guilt. Some of them were still alive and held important jobs. So, King Charles was very careful. He only asked Bouillé to do a quick, early check of the trial process. At this point, they only suspected an unfair judgment. They weren't yet planning to completely cancel the old decision.

Many important people had worked with the English in 1430. But after Charles took back Paris and Rouen, they changed sides. These people had a lot to lose if Joan's case was reopened. For example, Jean de Mailly, who was now a bishop, had signed papers helping those who worked against Joan in 1431. Another was Raoul Roussel, the archbishop of Rouen. He had strongly supported the English during Joan's trial. He also swore loyalty to Charles in 1450.

Bouillé only managed to call seven witnesses. His investigation suddenly stopped in March 1450. He didn't even get to read the full trial records. Most of the witnesses said the English wanted revenge on Joan. They also said the English tried to make King Charles VII look bad by calling Joan a heretic. Only one witness, Jean Beaupere, spoke against Joan. He refused to answer questions about the trial process. He said Joan was a fraud. Bouillé's report to the King did not include Beaupere's negative comments. The King closed the inquiry because he was busy with the war and other issues with the Pope. But Bouillé made it clear that clearing Joan's name was important for the King.

Cardinal d'Estouteville Steps In (1452)

Two years later, Cardinal Guillaume d'Estouteville strongly agreed that Joan's conviction hurt the King's honor. D'Estouteville was a special messenger from Pope Nicholas V. He was in France to try and make peace between England and France. But the French army was winning, and there were arguments with the Pope, which made his job hard.

D'Estouteville had several reasons to help Joan's case. First, his family had strongly supported King Charles VII. Second, he wanted to clear the King's name from any link to a convicted heretic. Third, he wanted to show his loyalty to France and the King.

In February 1452, King Charles finally met with d'Estouteville. As the Pope's messenger, d'Estouteville gave the investigation to Jean Bréhal, the main investigator for France. On May 2, 1452, Bréhal questioned witnesses. More detailed questioning began on May 8. This included most of the original trial members who were still alive. King Charles wanted to know the facts. But he was not happy about the Church's investigators running a big case in France without his full control. By December 1452, thanks to d'Estouteville, the case was moving forward on its own.

The problem of people who had worked with the English remained. In d'Estouteville's investigation in May 1452, two very important witnesses were not called. These were Raoul Roussel, the archbishop of Rouen, and Jean Le Maître, who was an investigator in 1431. By January 1453, d'Estouteville had returned to Rome. However, Bréhal had been busy gathering information and opinions from legal and religious experts. Even more importantly, Archbishop Roussel died the month before. This removed a big obstacle to reopening Joan's trial.

The New Trial and Clearing Her Name (1455–56)

Almost two years passed before a new effort began to clear Joan's name. The Church was busy trying to organize a war against the Ottoman Empire in 1453. The push for Joan's case came from her remaining family: her mother Isabelle and her brothers Jean and Pierre.

They sent a request to the new pope, Callixtus III. D'Estouteville, who was their representative in Rome, helped them. They asked for Joan's honor to be restored. They also wanted justice for the unfairness she suffered. They asked for her original judges to appear before a new court. Investigator Bréhal took up their cause. He traveled to Rome in 1454 to meet the Pope about Joan's trial.

In response, Pope Callixtus appointed three important French church leaders. They were to work with Bréhal to review the case and make a decision. These three men were Jean Juvenal des Ursins, the archbishop of Rheims; Richard Olivier de Longueil, the bishop of Coutances; and Guillaume Chartier, the bishop of Paris.

The Archbishop of Rheims was the most important of the three. He held the highest church position in France. However, he was hesitant about Joan's case. He even advised Joan's mother in 1455 not to continue her claim. This was because he had been the bishop of Diocese of Beauvais since 1432. This was the area where Joan had been found guilty just the year before. He also worried about claims that King Charles had won his kingdom with the help of a heretic. This would make the King look like a heretic too.

On November 7, 1455, the new trial began at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. Joan's family was there. Isabelle gave a powerful speech. She said that Joan was born in a proper marriage and raised with faith in God. She said Joan never did anything against her faith. But, Isabelle explained, "certain enemies... had her brought to a religious trial... in a trial that was dishonest, cruel, unfair, and without any right... they found her guilty in a terrible and criminal way, and put her to death very cruelly by fire... for the ruin of their souls and causing great, lasting harm to me, Isabelle, and my family."

The appeal process involved church leaders from France and Rome. It also included opinions from a scholar in Austria. A group of scholars looked at what 115 witnesses said. Most of them spoke about Joan's goodness, honesty, and bravery. The witnesses included many of the people who had been part of her first trial. There were also villagers who knew her as a child. Soldiers who fought with her and citizens of Orleans who met her when the city was saved also gave their stories. Many shared emotional details about Joan's life. Some of the original trial members were less helpful. They often claimed not to remember details from the 1431 trial.

After all the statements were taken and the scholars gave their decisions, Bréhal wrote his final report in June 1456. He suggested that Pierre Cauchon, the main judge, and his helpers might have been guilty of heresy.

The court declared Joan innocent on July 7, 1456. They canceled her original sentence. They said Joan had been tried because of "false accusations." Those accusations and Cauchon's sentence were to be torn from a copy of the trial records. They were then to be burned by the public executioner in Rouen.

The Archbishop of Rheims read the court's decision: "Considering the request of the d'Arc family against the Bishop of Beauvais, the person who started the criminal case, and the investigator of Rouen... We, in our court, with only God in our minds, say, announce, decide, and declare that the said trial and sentence (of guilt) were full of lies, false claims, unfairness, and mistakes in facts and law... to have been and to be void, invalid, worthless, without effect, and canceled... We announce that Joan did not get any bad reputation and that she shall be and is cleared of such." However, the judges did not say anything about Joan being a saint.

Joan's elderly mother lived to see the final decision. She was present when the city of Orleans celebrated the event. They held a big dinner for Investigator Bréhal on July 27, 1456. Isabelle's request for punishment against the original trial members did not happen. But the new decision cleared her daughter's name after twenty-five years.