Sabbatai Zevi facts for kids

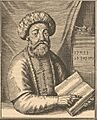

Sabbatai Zevi (born August 1, 1626 – died September 17, 1676) was a Jewish mystic and rabbi from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turkey). He was a follower of Kabbalah, a type of Jewish mysticism. Sabbatai Zevi claimed to be the long-awaited Jewish Messiah. He started a movement called the Sabbatean movement. His followers later became known as Dönme, which means "converts," or crypto-Jews, because they secretly kept their beliefs.

In February 1666, Sabbatai was put in prison in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) by the grand vizier, a high official of the Ottoman Empire. In September of that year, he was moved to Adrianople (modern-day Edirne) to be judged. He was accused of causing trouble and rebellion. Sabbatai was given a choice: face death or convert to Islam. He chose to convert to Islam and started wearing a turban. The Ottoman leaders then gave him a good pension for agreeing to their plans.

About 300 families who followed Sabbatai Zevi also converted to Islam and became known as the Dönme. Later, the Ottoman rulers sent him away twice. First, they sent him to Constantinople. When they heard him singing Jewish psalms with Jews, they sent him to a small town called Ulcinj in modern-day Montenegro. He died there, living alone.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Sabbatai Zevi was born in Smyrna, an Ottoman city, on a Jewish day of mourning called Tisha B'Av in 1626. In Hebrew, Sabbatai means Saturn. In Jewish tradition, the planet Saturn was sometimes linked to the coming of the Messiah.

Sabbatai's family were Romaniote Jews, meaning they were from the older Jewish communities in the Byzantine Empire. His father, Mordecai, was a poultry seller. During a war between Turkey and Venice, Smyrna became a busy trading center. Mordecai became an agent for an English trading company and became quite wealthy.

Following the custom of the time, Sabbatai's father had him study the Talmud, which is a collection of Jewish laws and traditions. He went to a yeshiva, a Jewish school, under Rabbi Joseph Escapa. Sabbatai wasn't very interested in Jewish law (called halakha), but he became good at understanding the Talmud. He was very interested in mysticism and Kabbalah, a secret Jewish tradition. He was especially influenced by a mystic named Isaac Luria.

Sabbatai was drawn to "practical Kabbalah." People who followed this believed they could talk to God and angels, predict the future, and do miracles by practicing asceticism (living a strict, simple life). He read a famous mystical book called the Zohar and did special purification exercises.

Sabbatai's Journey and Claims

Beliefs About the Messiah's Return

In the early 1600s, many people believed that the time for the Messiah to arrive was near. They thought that Jews would return to the land of Israel and become independent. Some Christian writers even pointed to the year 1666 as a special year for these events. This belief was very common in England.

Sabbatai's father worked with English traders in Smyrna, so it's possible Sabbatai heard about these ideas at home. Scholars are still studying how much these English and Dutch beliefs influenced Sabbatai's movement.

Claiming to Be the Messiah

Besides general beliefs about the Messiah, some Jewish mystical texts, like the Zohar, suggested that the Messiah would appear in 1648.

In 1648, Sabbatai told his followers in Smyrna that he was the Messiah. To show this, he started saying the Tetragrammaton, which is God's special name. In Judaism, only the high priest in the Temple in Jerusalem was allowed to say this name on the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur). This act was very symbolic and shocking. Sabbatai also claimed he could fly, but said he couldn't do it in public because his followers weren't "worthy enough." He also said he had visions of God.

Sabbatai was only 22, so he wasn't seen as a leading rabbi. Even though he had lived a strict, mystical life for years, the older rabbis in Smyrna were suspicious. His teacher, Joseph Escapa, watched him closely. When Sabbatai's claims became too bold, he and his followers were excommunicated, which means they were officially removed from the Jewish community.

Around 1651, the rabbis sent Sabbatai and his followers away from Smyrna. He later appeared in Constantinople in 1658. There, he met a preacher named Abraham Yachini, who supported his claim to be the Messiah. Yachini supposedly created an old-looking manuscript that said Sabbatai was the Messiah. It was called The Great Wisdom of Solomon.

In Different Cities

With this document, Sabbatai went to Salonica, a center for Kabbalah. He announced he was the Messiah and gained many followers. He held mystical events, like celebrating his marriage to the Torah (Jewish holy book). But the rabbis of Salonica sent him away.

He then traveled to different places like Alexandria, Athens, and Jerusalem, before settling in Cairo for about two years (1660–1662). In Cairo, he became friends with Raphael Joseph Halabi, a rich and powerful Jew who worked for the Ottoman government. Raphael Joseph lived a simple life and gave a lot of money to charity. He became a strong supporter of Sabbatai's claims.

Around 1663, Sabbatai moved to Jerusalem. He continued his strict practices, like fasting often. Many people saw this as proof of his great devotion. He was known for his good singing voice and attracted large crowds when he sang psalms or Spanish love songs, which he gave mystical meanings. He also prayed at the graves of holy people and gave sweets to children. Slowly, he gathered more followers.

At that time, the Jewish community in Jerusalem needed money to pay high taxes to the Ottoman government. Sabbatai was known to be friends with the rich Raphael Joseph Halabi in Cairo, so he was chosen to ask him for money. His success in getting the funds to pay the Turks made him even more respected. His followers believed his public career truly began after this trip to Cairo.

Marriage to Sarah

Another event in Cairo helped spread Sabbatai's fame. During a terrible event in Poland called the Chmielnicki massacres, a young Jewish orphan named Sarah was found by Christians and sent to a convent. After ten years, when she was about 16, she escaped. She believed that she was meant to be the bride of the Messiah, who she thought would appear soon.

When news of her story reached Cairo, Sabbatai said that a wife like her had been promised to him in a dream. He sent people to bring Sarah to him, and they were married at Halabi's house. Her beauty and unusual personality helped him gain new followers. His followers saw her difficult past as more proof that he was the Messiah.

Nathan of Gaza

With financial help from Halabi, a charming wife, and many followers, Sabbatai returned to Jerusalem. On his way, he passed through Gaza and met Nathan Benjamin Levi, known as Nathan of Gaza. Nathan became very important in Sabbatai's messianic journey. He acted as Sabbatai's main helper and said he was the prophet Elijah, who was supposed to announce the Messiah's arrival.

In 1665, Nathan announced that the time of the Messiah would begin in 1666. He said the Messiah would conquer the world without fighting and lead the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel back to the Holy Land.

The rabbis in Jerusalem were very suspicious of Sabbatai's movement and threatened to excommunicate his followers. Sabbatai decided Jerusalem wasn't the best place for his plans and left for his hometown, Smyrna. Nathan then declared that Gaza, not Jerusalem, would be the holy city.

On his way to Smyrna, Sabbatai was welcomed with excitement in Aleppo. When he arrived in Smyrna in the autumn of 1665, he was greatly honored. After some thought, he declared himself the Messiah during the Jewish New Year in 1665. He made this announcement in the synagogue, with horns blowing and shouts of "Long live our King, our Messiah!"

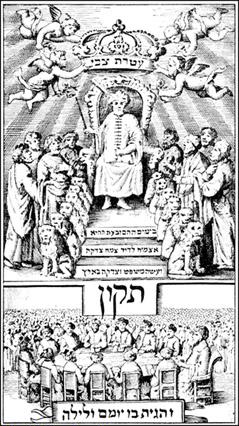

His followers then started calling him AMIRAH, which is a Hebrew abbreviation for "Our Lord and King, his Majesty be exalted."

Declared Messiah

With his wife's help, Sabbatai became the leader of the community and stopped anyone who opposed him. He removed the rabbi of Smyrna, Aaron Lapapa, and put Chaim Benveniste in his place. His fame spread far and wide. Jews in Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands heard about the events in Smyrna from reliable Christians. Henry Oldenburg, a famous German scholar, wrote to Baruch Spinoza, saying, "Everyone here is talking about a rumor of the Israelites returning to their own country... If the news is true, it could change everything."

Many important rabbis became Sabbatai's followers. Amazing stories spread and were widely believed. For example, people said that a ship with silk sails and ropes, manned by Hebrew-speaking sailors, appeared in northern Scotland. Its flag had the words "The Twelve Tribes of Israel." The Jewish community in Avignon, France, even prepared to move to the new kingdom in the spring of 1666.

Jewish people were ready to believe Sabbatai Zevi's claims because of the terrible situation they faced in the mid-1600s. Horrible attacks by Bohdan Khmelnytsky had killed about 100,000 Jews in Eastern Europe, which was about one-third of Europe's Jewish population at the time. Many Jewish learning centers and communities were destroyed. For most Jews in Europe, this seemed like the perfect time for the Messiah to bring salvation.

Sabbatai Zevi's Influence Spreads

Sabbatai's followers planned to get rid of many Jewish religious rules. They believed that in the time of the Messiah, these rules would no longer be needed. For example, the fast day of the Tenth of Tevet became a day of feasting and celebration.

This idea was seen as disrespectful by some, as Sabbatai wanted to celebrate his own birthday instead of a holy day. This caused anger and disagreement in communities. Many leaders who had supported the movement were shocked by these big changes. Some rabbis who opposed these changes barely escaped being killed by Sabbatai's followers.

In Constantinople

In early 1666, Sabbatai left Smyrna for Constantinople (Istanbul), possibly because city officials made him leave. Nathan of Gaza had predicted that once in Constantinople, Sabbatai would put the sultan's crown on his own head. To prevent any challenge to the Turkish Sultan's power, the grand vizier, Köprülüzade Fazıl Ahmed Pasha, ordered Sabbatai's immediate arrest and imprisonment.

However, his imprisonment did not stop Sabbatai or his followers. He was treated well in prison, perhaps because of bribes. This seemed to make his followers believe in him even more. Meanwhile, Nathan of Gaza and others spread amazing stories about the miracles "the Messiah" was supposedly doing in the Turkish capital. The hope for the Messiah continued to grow among Jewish communities around the world.

At Abydos Castle

After two months in a Constantinople prison, Sabbatai was moved to the state prison-castle at Abydos. Some of his friends went with him. Sabbatai's followers renamed the fortress Migdal Oz, meaning "Tower of Strength." Sabbatai arrived the day before Passover. He killed a paschal lamb for himself and his followers and ate it with its fat, which was against Jewish law. He reportedly said a blessing: "Blessed be God who has restored again that which was forbidden."

Sabbatai's rich followers sent him huge amounts of money. His wife, Sarah, and the cooperation of Turkish officials allowed Sabbatai to live almost like a king in the Abydos prison. Stories about his life there were exaggerated and spread among Jews in Europe, Asia, and Africa. In some parts of Europe, Jews even started removing the roofs of their houses to prepare for a new "exodus."

In almost every synagogue, Sabbatai's initials were displayed. Prayers for him were added, saying: "Bless our Lord and King, the holy and righteous Sabbatai Zevi, the Messiah of the God of Jacob." In Hamburg, people started praying for Sabbatai not only on Saturday (the Jewish Sabbath) but also on Monday and Thursday. Those who didn't believe were forced to stay in the synagogue and join the prayer with a loud "Amen." Sabbatai's picture was printed with King David's in most prayer books, along with his mystical sayings and practices.

These new practices caused great commotion in some communities. In Moravia, the excitement was so high that the government had to step in. In Sale, Morocco, the ruler ordered Jews to be persecuted. During this time, Sabbatai declared that the fasts of the Seventeenth of Tammuz and the Ninth of Av (his birthday) would now be feast days. He even thought about turning the Day of Atonement into a celebration.

Nehemiah ha-Kohen

While Sabbatai was in Abydos prison, something happened that led to his downfall. Two important Jewish scholars from Poland visited him in prison. They told Sabbatai that a prophet named Nehemiah ha-Kohen had announced the coming of the Messiah in their home country. Sabbatai ordered Nehemiah to come see him. Nehemiah traveled for three months and arrived at Abydos in early September 1666. Their meeting did not go well.

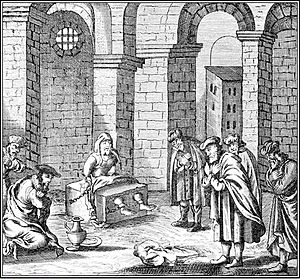

Converting to Islam

Nehemiah escaped to Constantinople. There, he pretended to convert to Islam so he could get an audience with a high official called the kaymakam. He told the kaymakam about Sabbatai's ambitions. The kaymakam informed Sultan Mehmed IV. Sabbatai was then moved from Abydos to Adrianople. The vizier gave him three choices: prove his divinity by surviving a volley of arrows (if the archers missed, he would be proven divine); be impaled (killed by a stake); or convert to Islam.

The next day, September 16, 1666, Sabbatai Zevi appeared before the sultan. He took off his Jewish clothes and put a Turkish turban on his head, completing his conversion to Islam. The sultan was pleased and gave Sabbatai the title (Mahmed) Effendi and made him his doorkeeper with a good salary. Sarah and about 300 families among his followers also converted to Islam. These new Muslims became known as Dönme. Sabbatai was told to marry a second wife to confirm his conversion. A few days later, he wrote to the community in Smyrna: "God has made me an Ishmaelite; He commanded, and it was done. The ninth day of my regeneration."

Disappointment and Continued Belief

Sabbatai's conversion shocked and disappointed his followers. Muslims and Christians alike made fun of them. Despite his change of faith, many of his followers still believed in him. They claimed that his conversion was part of God's plan for the Messiah. People like Nathan of Gaza encouraged this belief to keep the movement going. In many communities, the fast days of the Seventeenth of Tammuz and the Ninth of Av were still celebrated as feast days, even though rabbis had forbidden it.

Sometimes Sabbatai acted like a devout Muslim and spoke against Judaism. Other times, he spent time with Jews as if he were still one of them. In March 1668, he announced that he had been filled with the "Holy Spirit" during Passover and had received a "revelation."

Either Sabbatai or one of his followers published a mystical book claiming he was the true Messiah despite his conversion. This book said his goal was to bring thousands of Muslims to Judaism. However, he told the sultan that he was trying to convert Jews to Islam. The sultan then allowed him to spend time with other Jews and preach in their synagogues.

Final Years and Death

Over time, the Turks grew tired of Sabbatai's strange behavior and stopped paying him as a doorkeeper. In early 1673, the sultan sent Zevi away to Ulcinj (Dulcigno). His wife died there in 1674. Zevi then married Esther, the daughter of Rabbi Joseph Filosoff of Thessaloniki.

In August 1676, Sabbatai asked the Jewish community in Berat, Albania, for religious books. Shortly after, he died alone, possibly on September 17, 1676, which was the holy day of Yom Kippur. After his death, his widow, brother, and children from his first wife moved to Thessaloniki.

For a long time, people believed his tomb was in Berat, Albania, in a religious building near the Imperial Mosque. However, newer research in 1985 suggests he was actually buried in Dulcigno. His biographer, Gershom Scholem, mentioned that Dönme pilgrims from Salonica visited his tomb until the early 1900s.

By the 1680s, the Dönme gathered in Salonica, a city in Ottoman Greece with many Jewish people. For the next 250 years, they lived their own community life. They married among themselves, did business together, kept their own holy places, and passed down their secret traditions.

Legacy and Impact

By the 1800s, the Dönme became important in the tobacco and textile businesses. They started modern schools, and some members became active in politics. Some joined the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), a revolutionary group known as the Young Turks.

When Greece became independent in the 1910s, it expelled Muslims, including the Dönme, from its land. Most of them moved to Turkey, where they became more and more like other Turkish people by the mid-1900s.

Even though not much is known about them, different groups called Dönme still follow Sabbatai Zevi today, mostly in Turkey. Estimates of their numbers vary. Many sources say there are fewer than 100,000, but some claim there are several hundred thousand in Turkey. They are described as acting like Muslims in public while secretly practicing their own forms of mystical Jewish beliefs.

The Dönme eventually split into three groups, each with different beliefs. Scholars like Abraham Danon and Joseph Néhama wrote about this over a hundred years ago. More recently, Professor Cengiz Şişman published a new study called The Burden of Silence. According to a review, one branch called Karakaş follows practices influenced by Sufism (a mystical form of Islam). Another branch, the Kapancıs, has not been influenced by Islam at all and is now completely secular.

A house in the center of İzmir, near the Agora, has long been connected to Sabbatai Zevi. It was in ruins as recently as 2015 but has since been restored.

See also

In Spanish: Shabtai Tzvi para niños

In Spanish: Shabtai Tzvi para niños

- Frankism

- Jacob Frank

- Jewish Messiah claimants

- Jews in apostasy

- List of messiah claimants

- Schisms among the Jews

- "Who is a Jew?"

Images for kids

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |