Scottish poorhouse facts for kids

A Scottish poorhouse was a place that offered shelter to people in Scotland who were very poor and had nowhere else to go. Sometimes, these places were called workhouses, but in Scotland, they were almost always known as poorhouses. Unlike similar places in England and Wales, people living in Scottish poorhouses usually didn't have to work to earn their keep.

Scotland's Parliament started creating systems to help the poor as early as the 1400s. A law in 1424 sorted homeless people into two groups: those who could work and those who couldn't. Many laws followed, but they weren't very effective until the Scottish Poor Law Act of 1579. This law stopped people who were able to work from getting help, and it worked quite well.

Most help given was "outdoor relief," which meant giving people food, clothing, or money outside of a poorhouse. Even though 32 main towns were told to build "correction houses" for vagrants, it's not clear if any were actually built. By the 1700s, big cities like Aberdeen, Edinburgh, and Glasgow had poorhouses. Rich merchants or trade groups usually paid for these.

The system worked well enough in the countryside until the early 1800s. There, local church leaders and landowners were in charge of helping the poor. But in the crowded, poor areas of towns, the system couldn't cope. By the mid-1800s, Scotland faced a big economic crisis. This, plus a major split in the church called the Disruption of 1843, meant there were too many poor people and not enough help.

After the 1845 Poor Law Act, new local groups called parochial boards were set up. A central Board of Supervision gave advice and created rules for building new poorhouses. City poorhouses could hold up to 400 people, while rural ones held up to 300. By 1868, Scotland had 50 poorhouses. Strict rules decided who could get in, and a local Inspector of the Poor checked everything. The number of people in poorhouses was highest in 1906. The whole Poor Law system ended in the UK after the National Assistance Act in 1948.

Contents

Helping the Poor: A Look Back

Early Laws for the Needy

Helping poor people has been a part of society since medieval times. Scotland's Parliament first tried to deal with poverty in the 1400s. A law in 1424 divided homeless people into two groups: those who were strong enough to work and those who were not.

Laws about helping the poor were different in Scotland compared to England and Wales. In England, local areas had to provide work for poor people who could do it, but Scotland didn't have this rule. Also, if a poor person in Scotland was refused help, they could appeal the decision. This wasn't allowed in England and Wales.

Some early Scottish laws were quite strict. A 1425 law said that sheriffs could arrest beggars who were fit to work. If these beggars didn't find a job within 40 days of being released, they could be put in prison. Other laws were also made, but they often didn't work well. For example, a 1455 law even said beggars could be treated like thieves and executed.

The Scottish Poor Law Act of 1579 was managed by local officials. People who were poor but able to work were not allowed to receive help. Money collected at churches was usually enough to help those who couldn't work. This help was mostly "outdoor relief," meaning people received clothes, food, or money directly.

Later, in 1672, the responsibility for helping the poor in rural areas shifted. Local ministers, church elders, and landowners took charge. By 1752, landowners had more say because they paid most of the local taxes. This system worked quite well in the countryside until the early 1800s. But as towns grew and slums appeared, the system started to fail.

The 1672 Act also ordered 32 main towns to build "correction houses." These were places where homeless people would be held and made to work. Towns that didn't build them faced big fines. However, it's believed that almost none of these correction houses were ever built. "Outdoor relief" remained the main way of helping the poor.

Sometimes, local business people paid for poorhouses. For example, in Aberdeen, rich cloth merchants set up a place in the 1630s. In Edinburgh, the Canongate Charity Workhouse opened in 1761 and was run by several trade groups. Glasgow had its own Town's Hospital, which opened in 1731.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, many experts thought Scotland's system for helping the poor was better than England's. One writer, James Anderson, said in 1792 that Scotland's poor were "abundantly supplied." The Church of Scotland and even English officials praised Scotland's laws. However, by the 1840s, problems in Scotland's system became more noticeable.

The Poor Law Act of 1845

When Scotland and England joined together in 1707, Scotland kept its own legal system. This meant that the changes made to England's Poor Law in 1834 didn't apply to Scotland. However, Scotland's system for helping the poor also struggled with too many people needing help.

An extra problem in Scotland was the Disruption of 1843. This was when 40% of the Church of Scotland's clergy left to form a new church. This church split happened after a serious economic downturn in Scotland between 1839 and 1842. Since the poor relief system relied heavily on the church, a special committee was set up to study the problem.

This committee gathered information from almost every local area. Their suggestions were published in 1844 and became the basis for the 1845 Poor Law Act.

After the 1845 Poor Law Act became law, new local groups called parochial boards were created. These boards had the power to raise and use local money to help the poor. A central Board of Supervision in Edinburgh oversaw these local boards. Sir John McNeill led this central committee.

The central board advised the 880 local areas. But it had to approve any changes to existing poorhouses or plans for new ones. The new law allowed local areas to join together to run poorhouses. These were called "combination poorhouses." About three-quarters of Scotland's 70 poorhouses were run this way. Even so, most poor people still received "outdoor relief" rather than living in a poorhouse. By the 1890s, Scottish poorhouses could hold over 15,000 people, but usually, only about half that many lived there.

Life in Early Poorhouses

The changes made by the 1845 Poor Law in Scotland were not as strict as those in England's earlier law. So, changes happened slowly. Three years after the Board of Supervision started, it approved plans to make the existing Edinburgh poorhouse bigger. It also approved changes to Glasgow's Town's Hospital, which had been built in 1731.

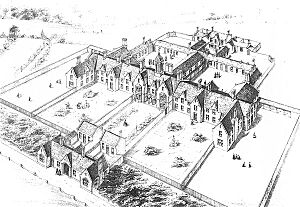

In 1847, a guide for designing new poorhouses was created. Eight new poorhouses were approved for building in 1848. An architecture firm, Mackenzie & Matthews, drew up plans for a poorhouse in Aberdeen. These plans, with a few small changes, became the standard design.

Poorhouses in cities could hold up to 400 people. Smaller versions for rural areas could hold up to 300.

Decisions about helping the poor mostly stayed with individual local areas. Local Inspectors of the Poor were appointed to check requests for help. Unlike in England and Wales, building poorhouses was optional in Scotland. Most local areas still preferred to give "outdoor relief."

The design of the model poorhouse showed this difference. Rooms near the entrance were set aside for giving out clothes and food to those getting outdoor relief. Scottish poorhouses also didn't rely on the money earned by residents to help pay for things, which was common in England.

The number of poorhouses built grew a lot between 1850 and 1868. In 1850, there were 21 poorhouses; by 1868, there were 50. Most of these were in or near Glasgow and Edinburgh. The Board of Supervision made sure that poorhouses were managed and run in a consistent way.

Getting In and Out

There were strict rules for getting into a poorhouse. People needed written permission to enter, usually signed by the local Inspector of the Poor. This permission had to be recent, usually no more than three days old. If someone lived far away, they had up to six days.

New arrivals were kept in a special area first. A doctor had to check them to make sure they didn't have any diseases. They were thoroughly searched, their clothes were taken away, and they were bathed. Then, they were given a standard uniform. Their own clothes were cleaned and stored until they left.

If a person wanted to leave the poorhouse, they just had to tell the House Governor 24 hours beforehand. This made it easy to leave, but getting back in required official permission again.

Officially, people in poorhouses were grouped into five categories:

- Children under two years old

- Girls under 15 years old

- Boys under 15 years old

- Adult males over 15 years old

- Adult females over 15 years old

Most children who needed long-term care (about 80-90%) were usually fostered or "boarded out" with families instead of staying in the poorhouse. The poorhouse buildings were designed so that people moved through different rooms for searching, bathing, and checking in. This was considered a very smart and practical design compared to buildings in England.

Later Changes and the End of Poorhouses

The Board of Supervision was in charge of the Poor Law in Scotland until 1894. That year, the Local Government Board took over. In 1919, the new Scottish Board of Health became responsible for poor relief. This was similar to what happened in England and Wales, where the Ministry of Health took over.

The number of people living in poorhouses reached its highest point in 1906. However, even then, less than 14% of all people receiving poor relief lived in a poorhouse. In England, this figure was much higher, at 37%.

By 1938, Scotland was spending more money on the Poor Law than it had in 1890. The period between World War I and World War II, known as the inter-war depression, was very hard for working-class people in Scotland. The difficulties they faced directly led to the National Assistance Act of 1948. This law finally ended the old Poor Law system across the entire United Kingdom.

See also

- Old Scottish Poor Law

- Scottish Poor Law

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |