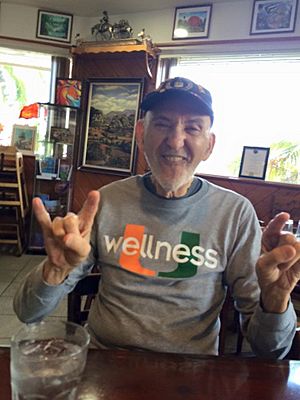

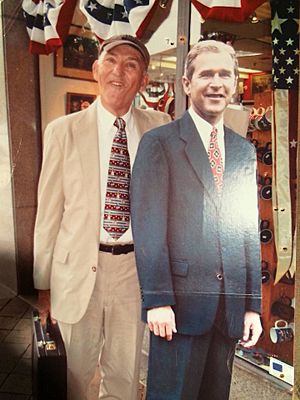

Sherwood Ross facts for kids

Sherwood Ross (born May 5, 1933 – died June 21, 2018) was an American journalist, activist, songwriter, and poet. He was famous for telling the world about James Meredith's important voter registration trip. This trip through Mississippi was called the "March Against Fear." Many people believe Ross helped save Meredith's life after he was shot during the march.

Contents

The "March Against Fear"

The march began on June 5, 1966, in Memphis. Only a few people, including James Meredith and Sherwood Ross, started the journey. Meredith wanted to encourage Black voters in Mississippi to use their right to vote. This march became a very important moment for the Civil Rights Movement.

The next day, a white gunman shot Meredith in Hernando, Mississippi. Ross had hoped to prevent such an attack by getting news reporters to follow the event. Even so, Meredith was ambushed. But the news coverage that followed made many people angry and brought civil rights leaders together.

Ross was quoted saying, "James, he's got a gun!" This was in his eyewitness story published in major newspapers. The next day, Ross appeared on NBC's "Today Show." He asked for more support. This led Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael, and other leaders to join the march in Mississippi. Ross later wrote that "Thousands from all races responded." He said the march became "a turning point and victory celebration" over unfair laws in Mississippi.

After leaving the hospital, Meredith rejoined the marchers on June 25. This was just before the 220-mile march ended in Jackson, Mississippi. When they reached the state capitol building, about 15,000 protesters had joined. This event became known as the "Last Great March of the Civil Rights Era." It also marked the start of the "Black Power" movement. Stokely Carmichael gave a powerful speech, making the slogan popular. A historian named Aram Goudsouzian wrote about Ross's part in the march in his 2014 book, Down to the Crossroads.

Goudsouzian says Ross helped save Meredith's life. Ross told the ambulance driver to hurry Meredith to the hospital or risk losing his job. Years later, Meredith himself said Ross was very important. He told the Chicago Sun-Times, "The Mississippi March Against Fear was a big deal primarily because of him." Ross had offered to help publicize the march after hearing Meredith's plans. After the shooting and the huge support that followed, Dr. King publicly thanked Ross. He thanked him for his work for racial equality.

Years later, Ross wrote that he wanted Meredith to be "surrounded by reporters." This was for when Meredith walked through areas where the Ku Klux Klan was strong.

Early Career and Activism

After serving in the U.S. Air Force, Ross went to the University of Miami. He was part of the debate team. He also wrote for the Miami Herald newspaper. In 1955, he earned the university's first degree in Race Relations.

In 1956, Ross became the first white editor at Ebony magazine. In 1958, he worked in politics. He was a speechwriter for Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley. He went back to journalism in 1962. He covered city issues for the Chicago Daily News. In 1963, he won an award for his news coverage of Dr. King's "March on Washington."

Inspired by people like Saul Alinsky, Ross left journalism again. He became an activist for civil rights. In 1964, he moved to New York. There, he became the news director for the National Urban League. This group was led by Whitney Young Jr. Ross wrote speeches for Young. He also secretly wrote a newspaper column for Young called "To Be Equal." In one column, Young asked book publishers to show more Black children and other minorities in books. Ross also came up with the idea for a "Domestic Marshall Plan." This plan suggested investing in Black communities in the U.S. It was like the Marshall Plan that helped rebuild Europe after World War II.

Fighting for Better Homes

In 1965, Ross moved his family to Washington, D.C. He became the public affairs director for the popular soul music radio station WOL (AM). A famous reporter named Carl Bernstein wrote about Ross's work there in 1967. Bernstein said Ross was called "the boss with the slum sauce" by the radio hosts. He was also known as "Robin Hood of Sherwood Jungle."

Ross created and hosted a radio show called "Speak Up." It aired late on Sunday nights. He wanted to help listeners have a stronger voice. Bernstein highlighted Ross’s "War on Slums." Ross would drive around the city in his WOL "Slummobile." He would show how bad housing conditions were. Kids would run alongside his car and tell him about apartments full of pests. He named bad landlords on the air. He helped fix hundreds of homes.

Bernstein quoted Ross yelling on the radio at one landlord. Ross told him not to kick out a tenant who had complained. Ross said, "Slum lord -- you have run-down, rat-infested, raggedy houses all over Washington." He promised to inspect all the landlord's bad properties. Ross told Bernstein that the "War on Slums" showed a radio station could help people. He said it could work against powerful city interests. Ross also said that "soul radio" stations like WOL helped civil rights leaders reach more people.

Public Relations Work

Ross left WOL that year. Soon after, he started his own public relations company, Sherwood Ross Associates. The New York Times wrote about his company in 1971. The article said Ross was "a pioneer" for his work helping magazines. He helped them get their stories mentioned in newspapers, on radio, and on TV. This helped many magazines get more readers.

A radio expert called Ross "a pioneer" for his work in the 1970s and 1980s. It was new for magazines to have their stories quoted in major newspapers back then. Ross helped publicize over 100 national magazines. His clients included The Atlantic, Business Week, and The New Yorker.

In 1981, Ross helped publicize "The Education of David Stockman" for The Atlantic Monthly. This started a national discussion about the government's economic ideas. It also helped the magazine sell 100,000 more copies. Ross continued to work in journalism and public relations for many years. He also did public relations for colleges like Johns Hopkins and Baylor. A newspaper called him "A Flack with a Conscience" in 2000.

Songs and Poems

In the 1980s, Ross was often seen at folk music events in New York City. He became known for performing unique songs like "Nightmare Room." He had five original songs recorded on the Fast Folk label. This label was later published by Smithsonian/Folkways Records.

After moving to South Dakota in the 1990s, Ross wrote plays. These included "Baron Giro" and "Yamamoto’s Decision." These historical plays had limited success.

When he returned to Miami in the early 2000s, Ross became a popular poet. He was a favorite at student poetry events. His poem "Hiroshima" was widely shared online. It honored the anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Ross also wrote a tribute poem to James Meredith called "Jesus in Mississippi." This poem was about the 1966 "March Against Fear." He won several awards from the Florida State Poets Association. He won for poems like "Bon Voyage" in 2013, and "The Egret" and "O, Guitar!" in 2014. He also wrote anti-war poems like "War No More."

Family and Life

Ross grew up in Chicago's Logan Square neighborhood. His father, Boris, came to the United States from Ukraine after fighting in the 1917 Russian Revolution. Boris Ross moved to Chicago and met Sherwood's mother, Libbe. She later became an elementary school teacher. The family moved to Miami in the late 1940s. Ross graduated from Miami Senior High.

Sherwood Ross had four children and five grandchildren. He was a squash champion in New York City in the early 1970s. He also competed in track and field events even into his 80s. He passed away in June 2018.

Images for kids

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |