Vote counting facts for kids

Vote counting is how we figure out who won an election. It's the process of adding up all the votes. This can be done by hand or with special machines. In some places, like the United States, this process of checking and confirming the results is called canvassing.

When there's only one choice on the ballot, counting votes is usually simple and often done by hand. If there are many choices on the same ballot, computers are often used to count quickly. Votes counted in different places must be sent accurately to a main election office.

Hand counts are usually very accurate, often within one percent. Computers are also accurate, but they can have problems like hidden software errors, broken parts, paper jams, or even hacks. Election officials try to keep election computers off the internet to prevent hacking. However, the companies that make these machines are online, and their updates can be hacked. Voting machines are also in public places on election day, making them easy targets.

Paper ballots and computer files of results are stored until they are counted. This means they need safe storage, which can be tricky. The election computers themselves are stored for years and checked briefly before each election.

Even with challenges to voting in recent years, many checks and balances are built into the voting system. These help make sure elections are fair and accurate, reducing the chance of mistakes or fraud.

Contents

Counting Votes by Hand

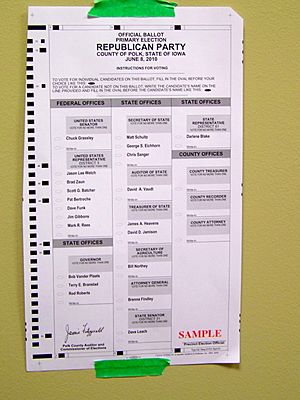

Counting votes by hand means using physical ballots that show what the voter chose. These paper ballots are taken from ballot boxes or envelopes. Then, people read and understand each vote and add up the results.

Hand counting can also be used to double-check results from automated counting systems. This is often done during election audits or recounts.

How Hand Counting Works

One way to count by hand is to sort ballots into piles for each candidate. Then, each pile is counted. If a ballot has votes for more than one election, the sorting and counting are repeated for each election. This method has been used in countries like Burkina Faso, Russia, and Sweden.

A different way is for one person to read each vote aloud while putting it into a pile. Other people can then keep their own tally and check the piles later. This method has been used in Ghana and Indonesia. These methods change the original order of the ballots, which can make it harder to match them with earlier records.

Another method involves one official reading all the votes on a ballot to one or more staff members, who then record the counts for each candidate. They do this for all elections on one ballot before moving to the next. Sometimes, ballots are projected onto a screen so many people can see and tally them.

A different approach is for three or more people to count ballots on their own. If most of them agree on their counts after a certain number of ballots, that result is accepted. If not, they all count again.

Some places scan all ballots and share the images online. This lets anyone count the votes by hand or with special software. Having different groups count independently helps protect against errors or hacks.

When Hand Counts Happen

Votes can be counted the night of the last voting day, as in Britain and Canada. Or they might be counted the next day, or even a week or two later in the US, after some special ballots are checked.

If counting isn't done right away, or if courts ask for ballots to be re-examined, the ballots need to be stored very safely. This can be a challenge.

In Australia, federal election ballots are counted at least twice. First at the polling place, and then again at counting centers starting the Monday after election day.

Mistakes in Hand Counts

Counting by hand can be tiring, so officials might lose track or make mistakes when reading their tally sheets.

Studies have shown that errors can happen in hand counts. For example, in New Hampshire towns in 2002, the average error for candidate totals was about 2.5%. In Wisconsin, recounts in 2011 and 2016 showed smaller average differences, around 0.28% and 0.18%.

In a 2016 race in Indiana, errors ranged from 3% to 27% for different candidates. This happened because tally sheets were confusing, or officials sometimes missed or double-counted ballots.

India checks a small sample of election machines by hand-counting paper records before releasing results. In 2019, they found small differences for 8 out of over 20,000 machines.

Experiments have shown that different hand-counting methods have different error rates. When one person read votes to two independent talliers, the average error was 0.5%. When ballots were sorted into stacks, the average error was 2.1%.

Intentional errors in hand-counting are a type of fraud. Having observers watch closely can help catch fraud, but whether their concerns are believed can vary. If only one person sees each ballot and reads the choice, there's no way to check their mistakes.

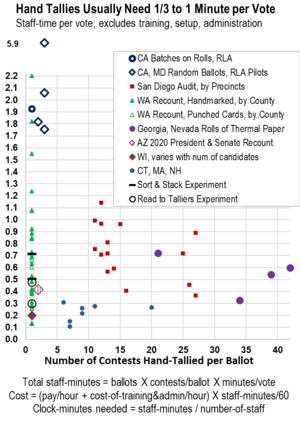

Time and Cost of Hand Counts

The cost of hand counting depends on how much staff are paid and how much time they need. Staff usually work in teams of two or three. Teams of four are even more secure but cost more. For example, if it takes one minute to check each vote, and staff are paid $15 an hour, it costs about 25 cents per vote.

One experiment found that sorting ballots into stacks took longer and had more errors than having two people read votes to two talliers.

Counting Votes by Machine

Machines can also count votes. Early mechanical voting machines had voters pull levers, push chips through holes, or press buttons. These actions would make a mechanical counter go up for the chosen candidate.

These older machines didn't create a record of individual votes, so it was hard to check them.

Mistakes in Mechanical Counting

It was possible to tamper with the gears or settings of these machines to change counts. Gears could also get stuck, causing them to miss votes. If machines weren't well-maintained, counters could stop working. Election staff could also read the final results incorrectly from the machine.

Counting Votes Electronically

Electronic voting machines are used around the world. When election commissions are honest and independent, machines can make counting faster, but they don't always make the process more open.

One study found that voting online or in person on election day at local polling places had the lowest costs per vote. This is because many voters could be served by a small number of staff.

Optical Scan Counting

- Further information: Voting machine#Optical scan (marksense), Electronic voting#Paper-based electronic voting system, and Electronic voting in the United States#Optical scan counting

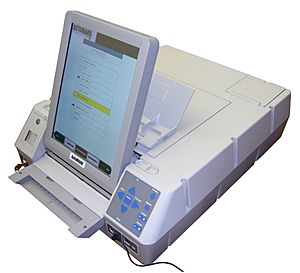

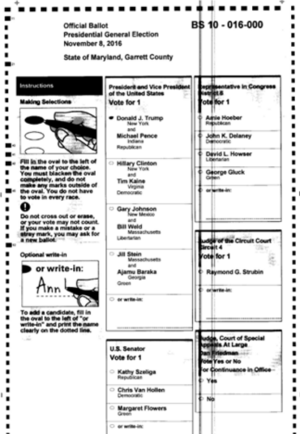

In an optical scan voting system, voters mark their choices on paper. These papers then go through a scanner. The scanner creates an electronic picture of each ballot, figures out the votes, adds them up for each candidate, and usually saves the image for later checking.

Voters can mark the paper directly, often by filling in an oval or using a special stamp. Or, voters might choose their selections on a screen, which then prints the chosen names onto a paper ballot. This screen and printer is called an electronic ballot marker (EBM) or ballot marking device (BMD). These devices help voters with disabilities. The paper it prints is the official ballot. Most voters don't check the paper to make sure it's correct.

Two companies, Hart and Clear Ballot, have scanners that count the printed names, which voters can check, instead of barcodes, which voters can't check.

How Optical Scans are Timed

Scanners are much faster than hand-counting. They are often used the night after an election to get quick results. The paper ballots and electronic records still need to be stored safely. This is important for checking that the images are correct and for any court challenges.

Mistakes in Optical Scans

Scanners use sensors to read ballots. A scratch or dust can cause a sensor to record a black line, which might look like a vote. A broken sensor can cause a white line. If these lines are in the wrong place, they could accidentally count as votes or no votes. Some offices clean scanners often to remove dust. Folds in the wrong places can also be counted as votes.

Software can also miscount. If it makes a big mistake, people usually notice and check. It's often hard to tell if an error was accidental or a hack.

- In a 2020 election, a company printed ballots where some candidate names were shifted. This made the scanner look in the wrong places and report incorrect numbers. It was caught because a popular candidate got very few votes, which seemed wrong.

- In a 2018 election, humid air caused ballots to jam in scanners or multiple ballots to go through at once.

- In a 2000 election, a programming error meant that votes for an entire political party were not counted for individual candidates. The software was fixed, and ballots were re-scanned to get correct counts.

Researchers have found security weaknesses in election computers. These flaws could allow people to change results without being noticed.

When a ballot marking device prints a barcode along with candidate names, the scanner counts the barcode, not the names. If there's a problem with how the barcode numbers match the candidate names, votes could be counted for the wrong candidates.

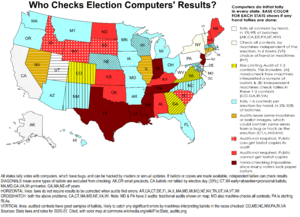

Some US states check a small number of votes by hand-counting or using different machines to double-check the original election machines.

Recreated Ballots

Sometimes, election staff create new paper or electronic ballots. This happens when original ballots can't be counted, perhaps due to tears, water damage, or folds that stop them from going through scanners. It also happens if voters mark ballots in ways machines aren't programmed to read, like circling a name instead of filling an oval.

As many as 8% of ballots in an election might need to be recreated. This process is also called reconstructing, replicating, remaking, or transcribing ballots.

Because recreating ballots could lead to fraud, it's usually done by teams of two people working together. They are often watched closely by teams from different political parties. However, this team process can be less secure if only one person looks at the original vote and another looks at the recreated vote.

When an election is audited, the original ballots should be used, not the recreated ones.

Cost of Scanning Systems

Optical scanners in the US have cost between $5,000 and $111,000 per machine. The price depends mostly on how fast they are. The initial cost can be $1 to $4 per registered voter. There are also annual fees, often 5% or more per year, plus extra fees for training and managing the equipment. Some places lease machines to keep costs steady.

Experts say that the steady income from past sales and the difficulty for new companies to enter the market reduce the motivation for companies to improve voting technology.

Direct-Recording Electronic Counting

With these machines, a touch screen shows choices to the voter. The voter picks their choices and can change their mind before casting the vote. Staff activate the machine for each voter to prevent repeat voting. Voting data and ballot images are saved in the machine's memory and can be copied out after the election.

These systems might also connect to a central location to send results and get updates. This connection can be a way for hacks or bugs to enter the system.

Some of these machines also print the names of chosen candidates on paper for the voter to check. This paper record can be used for election audits and recounts. This paper record is called a Voter-verified paper audit trail (VVPAT). Counting VVPATs can take 20–43 seconds of staff time per vote.

For machines without a VVPAT, there is no record of individual votes to check.

Mistakes in Direct-Recording Electronic Voting

These machines can have software errors. Since they don't use scanners, they don't have scanner errors. When there's no paper record, it's hard to notice or investigate most errors.

- In a 2018 study of direct-recording machines, memory cards failed in every election from 2010-2018. The study also found that candidate lists were different between central and local machines. This caused votes to be counted for the wrong elections.

- In a 2017 election, a programming error let voters vote more than once for the same candidate.

- In a 2011 election, a programming error gave two candidates very low vote counts. Voters provided statements saying they voted for them, so a judge ordered a new election, which they won.

A 2007 study found that election software relies on other software that is often unknown. This unknown software might have hidden weaknesses or harmful programs.

When a ballot marking device prints a barcode along with candidate names, the scanner counts the barcode, not the names. If there's a problem with how the barcode numbers match the candidate names, votes could be counted for the wrong candidates.

General Issues in Vote Counting

Safe Storage for Future Counts

If ballots or other paper or electronic records might be needed later for counting or court review, they must be stored very safely.

Election storage often uses tamper-evident seals. These seals are supposed to show if someone has opened the storage. However, seals can sometimes be removed and put back without damage, especially soon after they are applied. Photos taken when a seal is put on can be compared to photos taken when it's opened. It takes special training to spot small signs of tampering. Election officials often don't take enough time to check seals. If the storage is broken into, election results can't be properly checked and corrected.

Experienced testers can often get around physical security systems. Locks and cameras can be vulnerable. Guards might be bribed. It's often hard to follow all security steps, and many organizations don't want to know their weaknesses.

Security suggestions include making sure no one is ever alone with the ballots. This might mean using two hard-to-pick locks with keys held by different officials. It also means having different people identify storage risks than those who design or manage the system. Background checks for staff are also important.

Starting the vote count soon after voting ends makes it easier for different groups to guard the storage sites.

Safe Transport and Internet Use

Ballots can be carried safely to a central office for counting. Or, they can be counted at each polling place, either by hand or machine, and the results sent securely to the main election office. Transport is often done with representatives from different political parties to ensure honesty.

Postal voting is common worldwide. Voters who get a ballot at home can also deliver it by hand or have someone else deliver it. There are concerns that voters might be forced or paid to vote a certain way, or that ballots could be changed or lost during delivery. Ballots might also arrive too late to be counted.

Some places let ballots be sent to the election office by email, fax, internet, or app. Email and fax are not very secure. Internet voting has also had security problems in countries like Switzerland, Australia, and Estonia. Apps try to check if the correct voter is using them by asking for a name, date of birth, and signature, but this information can be faked. Apps have been criticized for being used on insecure phones.

See also

In Spanish: Escrutinio para niños

In Spanish: Escrutinio para niños

- Recount

- Tally (voting)

- Electronic voting

- Electronic voting in Switzerland

- Voting machine

- Electoral system

- Ballot

- Election audits

- Elections

- Electoral fraud

- Electoral integrity

- List of close election results

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |