Welsh coal strike of 1898 facts for kids

The Welsh coal strike of 1898 was a big disagreement between coal miners in South Wales and Monmouthshire and the people who owned the coal mines. It started because the miners wanted to change how their pay was worked out. This system was called the "sliding scale."

The strike quickly became a "lockout." This meant the mine owners stopped the miners from working for six months. In the end, the miners didn't get what they wanted, and the sliding scale stayed. This strike was a very important moment in Welsh history. It helped miners in the area join trade unions more than ever before. The South Wales Miners' Federation was a big union that started because of this strike.

Contents

Why Did the Miners Strike?

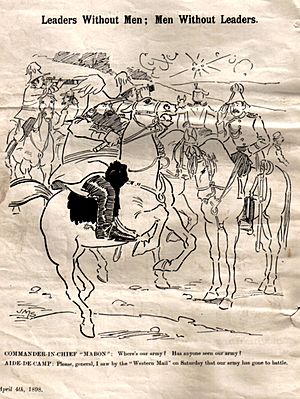

By late 1897, things were tense between the miners and the mine owners. The miners were led by a politician named William 'Mabon' Abraham.

The Sliding Scale Problem

The miners were unhappy about how they were paid. Their wages depended on a system called the "sliding scale." This system meant their pay changed based on how much coal they dug and also how much money the coal sold for.

Miners felt this system was unfair. They thought traders could trick the system. There was also no lowest pay level, which meant miners could earn very little. Many miners faced money problems because of this.

In September 1897, the miners said they would stop using the sliding scale in six months. The mine owners responded by saying they would end the miners' work contracts at the same time. This set the stage for a big conflict.

Trying to Solve the Strike

Before the deadlines in March 1898, both sides started talking to avoid a strike. The talks were still going on as the March 31st deadline got close. So, both sides agreed to keep talking until April 9th.

Talks Break Down

However, the discussions failed before the new deadline. The miners did not agree with the choices they were given. They all walked out of the mines together.

The miners had asked for a few things:

- A minimum price for coal of 10 shillings a ton.

- A sliding scale of 10%, not the 8.75% they had.

- An immediate pay raise of 10%.

The mine owners offered less than what the miners asked for on all these points.

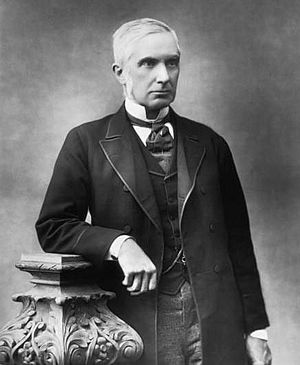

Help from Sir Edward Fry

Over time, the miners changed their main demand. They wanted to get rid of the sliding scale completely. But they still wanted the 10% pay raise.

The government's Board of Trade asked Sir Edward Fry to help solve the problem. The miners liked this idea, but the mine owners refused to meet with him.

Sir Edward kept trying. The miners eventually agreed to ask for less money. In return, they wanted a new group called a Conciliation Board. This board would help set wages if coal prices dropped too low.

The mine owners seemed interested in these ideas. But before they could discuss them, the miners' representatives brought back their original demands. So, the talks broke down again. After this second failure, Sir Edward told the Board of Trade that the owners were stubborn and the workers didn't have strong leaders.

What Happened After the Strike?

By August, the miners decided to focus on one main issue: keeping the sliding scale, but with a guaranteed minimum pay level.

In the end, the miners accepted a 5% pay raise right away. The mine owners also promised that if wages fell too low, the miners could give six months' notice to end the sliding scale.

The strike also meant the end of "Mabon's day." This was a holiday on the first Monday of every month that miners used to get. The strike officially finished on September 1, 1898.

The Birth of the Fed

The strike showed that the miners needed better organization and leadership. Because of this, the South Wales Miners' Federation, also known as 'the Fed,' was created. William Abraham became the president of this new group.

After such a long strike with no pay, miners in South Wales became much more determined. Many more men started joining trade unions, something that hadn't happened much in the area before.