Şehzade Mustafa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Şehzade Mustafa |

|

|---|---|

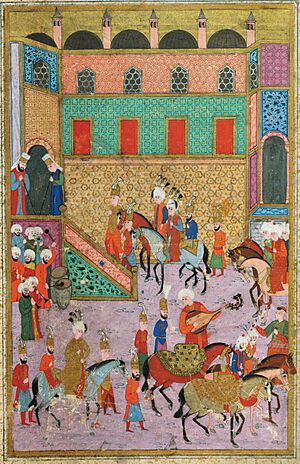

An Ottoman miniature of Mustafa

|

|

| Governor of Amasya | |

| Tenure | 16 June 1541 – 6 October 1553 |

| Governor of Manisa | |

| Tenure | 3 May 1533 – 16 June 1541 |

| Born | c. 1516/1517 Manisa Palace, Manisa, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 6 October 1553 (aged 36–37) Ereğli, Konya, Ottoman Empire |

| Burial | Muradiye Complex, Bursa |

| Issue | Fatma Sultan Nergisşah Sultan Şehzade Mehmed Şah Sultan Şehzade Ahmed Şehzade Orhan |

| Dynasty | Ottoman |

| Father | Suleiman the Magnificent |

| Mother | Mahidevran Hatun |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Şehzade Mustafa (Ottoman Turkish: شهزاده مصطفى; around 1516 or 1517 – October 6, 1553) was an Ottoman prince. He was the son of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and his mother, Mahidevran Hatun. Mustafa served as a governor in different cities. He was governor of Manisa from 1533 to 1541. Later, he governed Amasya from 1541 until 1553. Sadly, he was executed by his father's order. This happened because he was accused of planning against the ruler.

Contents

Early Life of Prince Mustafa

Mustafa was born in Manisa around 1516 or 1517. His father, Suleiman, was a prince at that time. His mother was Mahidevran Hatun. When Suleiman became Sultan in 1520, Mustafa and his mother moved to the Old Palace in Constantinople. After his brothers Murad and Mahmud passed away in 1520, Mustafa became the only son who could take over the throne. An ambassador from that time said that Mustafa was his mother's greatest joy.

Mustafa's Time as Governor

Mustafa was known for being very smart and brave. He was well-liked by the Janissaries, who were the Sultan's elite soldiers. Many people thought he would become a strong leader.

On May 3, 1533, he became the governor of Saruhan. Mustafa was put in charge of Anatolia in 1534 and 1538. This was when his father, Sultan Suleiman, was away fighting wars. In 1534, a high-ranking official named Ibrahim Pasha wrote to Mustafa. He said he was Mustafa's "faithful friend" and hoped to meet him soon.

Around 1540, a traveler described Mustafa's court in Diyarbakır. He said the prince had a wonderful and grand court, almost as impressive as his father's.

Moving to Amasya

On June 16, 1541, Mustafa was moved to Amasya. His son, Şehzade Mehmed, was born there in 1546. Mustafa felt that his father preferred his half-brothers. He was upset about leaving Saruhan, which was a special place for princes. Even though he received more money, he didn't like moving to Amasya.

Saruhan was later given to Mehmed, Sultan Suleiman's oldest son with Hürrem. After Mehmed's sudden death in 1543, Saruhan went to their second son, Selim. Mustafa felt left out, even though many military leaders supported him.

Meeting His Father

In 1548, Sultan Suleiman traveled across Anatolia for a war. He asked Mustafa to join him for a few days. A special report describes their meeting in May. The Sultan showed affection towards Mustafa, even though they had some disagreements before. Mustafa received a warm welcome from important officials and the army. He went to his father's tent, and their talk showed Mustafa's loyalty. The prince felt great relief and joy. A history book written for Suleiman also highlighted Mustafa's special treatment.

A Supporter of Arts and Justice

While governing Amasya, Mustafa became known for supporting poetry and learning. He was also seen as a protector of the people and a fair judge. He was friendly with military leaders.

In 1549, the governor of Erzurum was killed. Mustafa asked for help from Istanbul to get revenge. However, Rüstem Pasha, who was married to Mustafa's half-sister, did not send help. Rüstem Pasha thought Mustafa would gain too much fame by winning.

In 1550, robbers from Iran attacked villages in eastern Anatolia. Again, Mustafa asked for help, but Rüstem Pasha refused. Rüstem Pasha even tried to spy on Mustafa by sending a new official, but it didn't work.

Who Would Be the Next Sultan?

Many people believed Mustafa would become the next Sultan. In the late 1540s, a Venetian ambassador noted his military skills. He also saw that the Janissaries liked him very much. They wanted him to be the next Sultan. Another ambassador said the same thing just before Mustafa's death.

In 1549, a French diplomat wrote about the Sultan's illness. He talked about Mustafa possibly becoming Sultan. But he also worried that Mustafa's rise might put his brothers' lives in danger.

Sultan Suleiman was getting older and had health problems. He let his officials lead military campaigns. This might have been because he didn't want to leave the capital. He also feared that his sons might fight over who would rule before he died.

Some officials, including Rüstem Pasha, wanted to make peace with other countries. This was because of disagreements among Suleiman's sons. There were rumors that Rüstem Pasha wanted to remove Mustafa from the path to the throne. He wanted to help Selim, another son, become Sultan.

Rüstem Pasha, Hürrem (Suleiman's wife), and Mihrimah (Mustafa's half-sister) worked together. They wanted either Selim or Bayezid to become the next ruler. Rüstem Pasha made a plan against Mustafa. He tried to make it look like Mustafa was working with the Safavid ruler. He even forged Mustafa's seal to send a fake letter.

Mustafa also sought support for himself. He wrote a letter asking for help from a high-ranking military official. He made it clear he would wait for his father's death. But he also hinted that he would reward his supporters and punish those who didn't help him. He believed he was the only prince fit to be Sultan. He even sent a messenger to Venice to get support before his execution.

The Safavid Campaign and Mustafa

In late 1552, Rüstem Pasha led the army to fight the Safavids. But there were problems within the army. Many soldiers believed Mustafa would soon become Sultan. Rüstem Pasha camped near Konya, but he was losing control of his men. Some Janissaries even went to Amasya to show their loyalty to Mustafa.

Rumors also spread that Sultan Suleiman was very sick. This made the situation difficult for Rüstem Pasha. He feared that if the Sultan died, or if Mustafa took control of the army, he would be in trouble. So, Rüstem Pasha likely convinced Suleiman to take action against Mustafa.

A Tragic Plan

From the army camp, Rüstem Pasha sent messages to Suleiman. He said Mustafa was planning to take power. To make his claim seem true, Rüstem Pasha reportedly made a copy of Mustafa's seal. He then wrote a fake letter to the Safavid ruler, suggesting an alliance. The Safavid ruler replied, not knowing it was a trick. Rüstem Pasha's men intercepted this reply. They sent it to Suleiman as proof that Mustafa was a traitor.

Rüstem Pasha's plan worked. He was called back to Constantinople. Sultan Suleiman then took command of the army himself. The Sultan's journey was delayed, possibly due to his health. He might have also been discussing with Rüstem Pasha how to deal with Mustafa.

On August 28, 1553, Suleiman left his capital with Rüstem Pasha. He displayed seven banners, showing his power. This was to counter rumors about his oldest son becoming Sultan. Suleiman set up camp near Ereğli.

Mustafa, hoping to make peace, arrived near the camp on October 5. He was greeted warmly by officials and given gifts. Mustafa knew the situation was delicate. He hoped for a reconciliation with his father. His presence showed that refusing to come would have been seen as an act of rebellion.

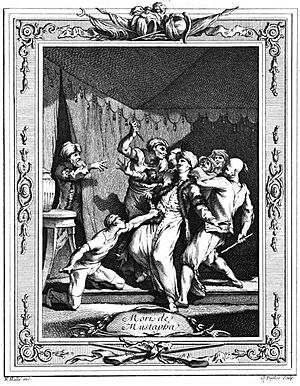

The Sad Execution

On October 6, 1553, around noon, Mustafa rode to his father's tent. He followed tradition and left his weapons outside. His companions stayed outside too. When Mustafa entered the tent, he was attacked by executioners. After a struggle, he was killed.

Some of his closest friends were also killed. Others were sent away to different parts of the empire. All his belongings, including the gifts he received the day before, were taken.

After a sad funeral prayer in Ereğli, Mustafa's body was quickly taken to Bursa. This city was an old Ottoman capital and a burial place for many royal family members. His mother went with his body. His son, Mehmed, who had been moved there, was also executed in May 1554. He was buried next to his father.

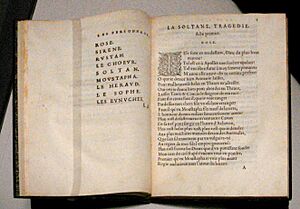

Mustafa's death caused a lot of sadness and anger among the people. Sultan Suleiman quickly removed Rüstem Pasha from his high position. People expressed their anger in poems. One famous poem blamed "Rüstem's conspiracy and deceit." Poets called Mustafa a "martyr," meaning someone who died for a cause. They said the claims of him working with the Safavid ruler were false. People criticized Rüstem Pasha, Hürrem, and even the Chief Jurist.

Mustafa's Family

Sons

Mustafa had at least three sons. All his sons who were alive when he died were executed shortly after by their grandfather, Sultan Suleiman.

- Şehzade Mehmed (born 1546 in Amasya – died May 1554 in Bursa).

- Şehzade Ahmed (likely died in 1553).

- Şehzade Orhan (died in 1552 or 1553).

Daughters

Mustafa had at least three daughters:

- Fatma Sultan. She married Boşnak Ahmed Pasha in 1552.

- Nergisşah Sultan (born 1536 in Manisa – died 1592). In 1554, after her father's death, her grandfather Suleiman arranged for her to marry Cenâbî Ahmed Pasha. He was much older than her father. She became a widow in 1562.

- Şah Sultan (around 1547 in Amasya – died November 2, 1577). She married Abdülkerim Ağa, a general of the Janissaries, between 1562 and 1567.

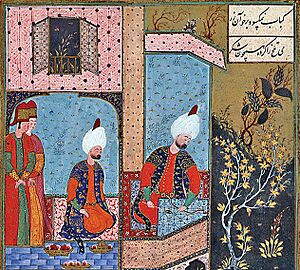

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Şehzade Mustafa para niños

In Spanish: Şehzade Mustafa para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |