Ahupuaʻa facts for kids

Ahupuaʻa (say: ah-hoo-poo-ah-ah) is a special Hawaiian term for a traditional way of dividing land. Imagine a slice of land that stretches from the top of a mountain all the way down to the ocean! These areas usually included a whole river system and all the natural resources from the mountains, through the valleys, and into the sea.

In ancient Hawaii, the ahupuaʻa system was very important for how people lived and shared resources. Each ahupuaʻa was designed to have everything the people living there needed. This included wood from trees like Koa for building homes, fresh water, and different kinds of food such as fish and taro. This smart system helped communities be self-sufficient and work together.

Contents

How Land Was Divided in Ancient Hawaii

Ancient Hawaiians had a clever system for organizing their land. It was like a set of nesting dolls, with bigger areas containing smaller ones:

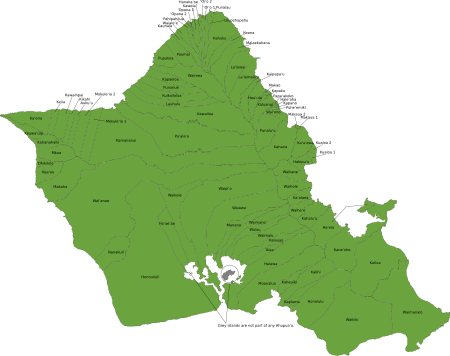

- Mokupuni: This was a whole island, like Hawaiʻi or Oʻahu.

- Moku: These were the largest parts of an island.

- Ahupuaʻa: These were the land divisions from mountain to sea.

- ʻIli: These were smaller sections within an ahupuaʻa.

Some stories say that a great chief named ʻUmi-a-Līloa helped divide the land into ahupuaʻa. However, many believe this system grew naturally. Communities often formed along stream systems, and sharing water was a big part of how they lived and made rules.

Farming and Resources in Ahupuaʻa

Hawaiians were expert farmers. They used two main farming methods:

- Irrigated systems: Here, they grew mostly taro (kalo), which needs a lot of water.

- Rain-fed systems: In these areas, they grew sweet potatoes (ʻuala), yams, and dryland taro. This type of farming was also called the mala. They also grew coconuts (niu), breadfruit (ʻulu), bananas (maiʻa), and sugar cane (kō). Sometimes, kukui trees were planted to give shade to the mala crops. Farmers carefully chose the best spots for each plant.

Hawaiians also raised animals like dogs, chickens, and pigs. Many families had their own small gardens at home. Water was super important! It was used for fishing, bathing, drinking, and watering gardens. They even had special systems to raise fish in rivers and near the shore.

An ahupuaʻa usually stretched from the top of a mountain (often a volcano) down to the ocean. It often followed the path of a stream. Each ahupuaʻa had a lowland farming area (the mala) and a forested area higher up. The size of ahupuaʻa changed depending on the resources available and how the area was politically divided.

Hawaiians lived with great respect for nature. They practiced aloha (respect), laulima (cooperation), and mālama (stewardship). This helped them achieve pono (balance) in their lives. They believed that the land, the sea, the clouds, and all of nature were connected. They used all resources wisely to keep this balance.

To make sure resources lasted, leaders called konohiki and priests called kahuna helped. They would set rules, like not fishing for certain types of fish during specific seasons. They also managed when people could gather plants.

What "Ahupuaʻa" Means

The word "Ahupuaʻa" comes from two Hawaiian words:

- ahu: meaning "heap" or "pile of stones"

- puaʻa: meaning "pig"

Traditionally, the borders of an ahupuaʻa were marked by piles of stones. People would place offerings, often a pig, on these stone piles for the island chief.

How Ahupuaʻa Were Managed

Each ahupuaʻa was divided into smaller sections called ʻili. These ʻili were then divided into even smaller plots of land called kuleana. These kuleana were farmed by the common people. These farmers would pay taxes, often through labor, to the land overseer. These taxes helped support the chief.

There were two main reasons why this land division system worked so well:

- Easy Travel: In many parts of Hawaiʻi, it was easier to travel up and down a stream valley than to go across different valleys.

- Self-Sufficiency: Having all the different climate zones and resources (from mountain to sea) in each land division meant that each ahupuaʻa could provide most of what its people needed.

Each ahupuaʻa was led by an aliʻi (a local chief). A manager called a konohiki helped run the ahupuaʻa day-to-day. The ruling chief would give control of ahupuaʻa to other important aliʻi. On larger mountains, some ahupuaʻa stretched very high up. These large, high-elevation ahupuaʻa were very valuable. They offered special resources like high-quality stone for tools and rare bird chicks. High-ranking aliʻi or even the high chief himself often kept control of these important areas.

Ahupuaʻa Today

After a big land change called the Great Māhele in 1848, most ahupuaʻa were split up. However, a few large ahupuaʻa, like Manukā and Puʻu Waʻawaʻa on Hawaiʻi island, stayed mostly together. This was because they were "crown lands" owned by the monarch.

Even though many ahupuaʻa were divided, their old boundaries still affect things today. For example, the ahupuaʻa of Keaʻau, near Hilo, was once bought as one big piece of land for farming. Later, much of this land was sold off to become large neighborhoods. The line between these new areas often follows the old ahupuaʻa boundary. This boundary even follows the edge of an ancient lava flow!

Many towns in Hawaiʻi still have names from the old ahupuaʻa. In West Maui, towns like Honokōhau, Honolua, Kapalua, Nāpili, and Lahaina are named after the ahupuaʻa they are in. Each of these towns still has its own unique feel.

See also

In Spanish: Ahupua'a para niños

In Spanish: Ahupua'a para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |