Alexander Findlater facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Findlater

|

|

|---|---|

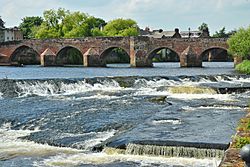

Burtisland, Findlater's birthplace

|

|

| Born | 4 September 1754 |

| Died | 3 December 1839 Anderston and then Linn Cemetery

|

| Occupation | Collector of Excise |

Alexander Findlater was a close friend and colleague of the famous Scottish poet Robert Burns. He was also Burns's boss in the Excise service, which collected taxes. Findlater knew Burns very well. After the poet's death, Findlater strongly defended Burns against unfair stories written by some authors like Robert Heron, Allan Cunningham, and James Currie.

Life and Career

Alexander Findlater was born in 1754 in Burntisland, a town in Fife, Scotland. His father, James Findlater, was an army officer who later became an Excise officer, just like Alexander would.

In 1774, Alexander became an Excise officer himself. By 1778, he was working in Coupar Angus. The Excise service was important for the government, as its officers collected taxes on goods like alcohol and tobacco.

Findlater quickly moved up in his career. In 1790, he became an Examiner of Excise. By April 1791, he was promoted to Supervisor of Excise. He and his family then moved to Dumfries, arriving about six months before Robert Burns moved there too.

In 1797, Findlater was promoted again to General Supervisor in Edinburgh. Later, in 1811, he became a Collector in Glasgow. He retired in 1825 at the age of 71, after many years of service. Alexander Findlater passed away in 1839. His grave was later moved to Linn Cemetery in Glasgow.

Friendship with Robert Burns

Alexander Findlater was Robert Burns's direct supervisor in the Excise service in Dumfries. They also became good friends. Findlater often defended Burns against untrue claims about his work and character.

In December 1791, Findlater wrote a letter praising Burns. He said Burns was "an active, faithful and zealous officer." He also said Burns was "capable of achieving a more arduous task than any difficulty that the theory or practice of our business can exhibit." This shows how much Findlater respected Burns's abilities.

Findlater even spoke up for Burns when the poet wanted to move to a different part of the Excise service. This new role would have given Burns an extra £20 in salary.

In June 1792, Findlater spent a whole day with Burns, visiting different businesses like breweries and wine shops. Findlater noted that Burns was new to some parts of the job but promised to pay more attention. He added that Burns was "rarely deficient" in his duties.

Findlater defended Burns in December 1792 when some people accused the poet of being disloyal or not doing his job well. Findlater knew these claims were false.

From late 1794 to early 1795, Findlater was ill. Burns took over his duties as Acting Supervisor for several months. This was a very tough job, especially in the cold winter of 1795. Burns often had to ride his horse for forty miles through the snow. His day would start before dawn and end almost at midnight. This hard work unfortunately affected Burns's health.

Some people later claimed that Burns was not a good officer. However, Findlater pointed out that the Excise service would not have promoted Burns to Acting Supervisor if he had problems with his work. Findlater greatly admired Burns's hard work and dedication. This strengthened their friendship and gave Findlater a deep understanding of Burns's true character.

Findlater joined the Royal Dumfries Volunteers, a local defense group, shortly after Burns and their friend John Syme. Findlater was on a committee that suggested asking the public for money to buy uniforms. Burns and others disagreed with this idea.

Burns also added Findlater's name to the list of people who received The Bee magazine every week. This magazine was produced by Dr. James Anderson, a well-known writer and economist.

After Burns's death, Findlater became a strong supporter of his friend's memory. In 1815, he wrote an important letter defending Burns's behavior and character. He said he saw more of Burns than almost anyone else, especially in the poet's later years in Dumfries. Findlater continued to defend Burns against untrue stories spread by other writers like Robert Heron and Allan Cunningham.

Findlater was one of the few people who sat with Burns during his final days.

It's interesting that James Currie, who wrote a biography of Burns, never tried to contact Findlater. Findlater could have given him a firsthand account of Burns's life in Dumfries.

Findlater wrote about his connection with Burns: "My connection with Robert Burns commenced immediately after his admission to the Excise, and continued to the hour of his death." He added that he was in a good position to observe Burns's conduct.

Findlater was upset by the unfair things written about Burns after his death. He said that some writers tried to make Burns look bad. They twisted his social habits and independent spirit into accusations of neglecting his duties or family, even without proof. Findlater hoped these false claims would be properly addressed.

Letters and Poems

Burns and Findlater often wrote letters to each other. Their letters show their friendship and professional relationship.

In October 1789, Burns wrote to Findlater from Ellisland Farm, thanking him for speaking well of him to the Excise officials in Edinburgh. Burns promised to always act in a way that would stand up to scrutiny.

Burns also sent Findlater a gift of fresh eggs from his farm. He included a sweet note explaining that his wife knew he loved new-laid eggs.

Burns even wrote a short poem about Findlater:

|

"The Exciseman and the Gentleman in one, |

In June 1791, Burns wrote to Findlater about a mistake he made while checking a business's stock. This shows that even though they were friends, Findlater was still Burns's boss. Burns explained the situation and worried about how it might affect his reputation as an officer. He mentioned that the mistake might have been caused by a "Smuggler," someone who tries to avoid paying taxes.

In January 1794, Burns wrote to Robert Graham of Fintry with ideas to improve the Excise service. He mentioned that Findlater, his supervisor, was "one of the first... Excisemen" and "one of the worthiest felloes in the universe." Burns said he didn't want Findlater to know the ideas were his, because Findlater was a close friend and he didn't want to hurt him.

In May 1794, Burns introduced Findlater to a bookseller in Edinburgh, calling him "a gentleman of great information & the first worth." Burns also said he owed Findlater a lot.

Findlater's wife, Mrs. Findlater, also played a small part in preserving Burns's writings. She and another friend of Burns, Mrs. Lorimer, would give their doctor, Dr. James Adams's father, many of Burns's handwritten papers instead of paying for medical services. Dr. Adams later remembered that he and Mrs. Findlater's son would often use the blank sides of these important papers to draw pictures!

See Also

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |