Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture facts for kids

The Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture is a special place that is part of the College of Charleston in South Carolina. It is located in Charleston, South Carolina, at the same spot where the Avery Normal Institute used to be. This historic school was very important. From 1865 to 1954, it helped Black students get ready for important jobs and leadership roles. It was also a central place for the African-American community in Charleston.

In 1978, former students of the Avery Normal Institute, led by Lucille Whipper, created the Avery Institute of Afro-American History and Culture. They worked with the College of Charleston to open the Avery Research Center in 1985. Their goal was to keep the history of the Avery Normal Institute alive. They also wanted to teach everyone about the history and culture of African Americans in Charleston and the surrounding Lowcountry area of South Carolina.

Today, the Avery Research Center lets people explore old documents and items, both online and in person. It offers guided tours and hosts workshops. The center also presents talks and performances. You can also see physical and online museum exhibits there. The Avery Research Center Archives currently holds over six thousand original records and other writings. These items tell the story of African American history, traditions, and influences.

Contents

History of Avery

Avery Normal Institute: 1865–1954

A school for African American students started in Charleston in 1865. It was founded by the American Missionary Association (AMA) from New York. The school was first called the Tappan School. It was named after Lewis Tappan, who worked to end slavery. Soon after, it was renamed the Saxton School, after Union General Rufus B. Saxton. He was part of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which helped formerly enslaved people.

The school eventually became the Avery Normal Institute. It was the first approved high school for African Americans in Charleston, South Carolina. It quickly grew to offer an important program for training teachers.

At first, the school was in different buildings in Charleston that the government used during the Reconstruction era. White missionaries from the North and free Black people from Charleston worked as staff. Thomas W. Cardozo was the first principal. After some issues from his past, Francis Cardozo became the second principal. He led the school from 1866 to 1868.

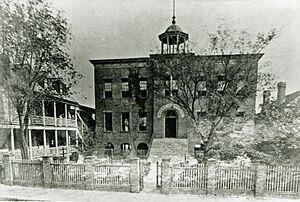

Francis Cardozo worked hard to build a permanent school building. He convinced a leader from the AMA to get $10,000 from the estate of Reverend Charles Avery. With more help from the Freedmen’s Bureau, the new school building opened on May 7, 1868. It was named the Avery Normal Institute. Cardozo quickly expanded the school's purpose beyond just elementary and high school education. He added teacher training programs.

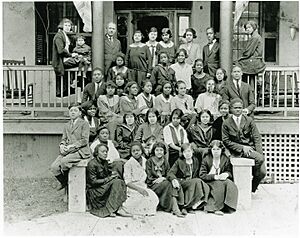

Before 1919, a rule in Charleston stopped African Americans from teaching in most of the city's Black public schools. Because of this, many Avery graduates, like Septima Clark, taught in small, one-room schools across South Carolina. They often taught in the rural Lowcountry region around Charleston. Later Avery principals, like Morrison A. Holmes, continued the school's focus on teacher training and classic education. However, the teachers were white missionaries, not local African Americans like the Cardozo brothers.

In 1917, Avery helped create the city's branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The first president of the Charleston NAACP was the famous artist Edwin Harleston. He had graduated from Avery in 1900.

Benjamin Cox was principal from 1915 to 1936. His wife, Jeanette Keeble Cox, made the school better by adding new facilities and courses. She also brought in cultural activities like plays and music shows. Cox was the first Black principal at Avery since Cardozo. Later Avery Principals, Frank DeCosta (1936–1940) and L. Howard Bennett (1941–1943), made the school more modern. Principal John F. Potts oversaw Avery becoming a public school in 1947.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court made a decision called Brown v. Board of Education. After this, the county school board closed Avery Normal Institute. They combined its students and teachers with Burke High School. They said it was for financial reasons.

The Avery Normal Institute prepared its students for professional careers and leadership roles. Avery students and teachers were often active in the state’s civil rights movement in the 1950s and 60s. This was true even after the school closed. For example, Avery graduates who became important civil rights activists included Cecelia Cabaniss Saunders, Septima Clark, J. Andrew Simmons, John Henry McCray, John H. Wrighten, Jr., Arthur J. Clement, Jr., and J. Arthur Brown.

Avery Institute for Afro-American History and Culture

After 1954, Dr. John Palmer bought the Avery buildings. He ran Palmer Business College there for over twenty years. Then, the college moved to another location. In 1978, a group of Avery graduates, called "Averyites," and friends of Avery formed The Avery Institute of Afro-American History and Culture. Their goal was to get the old Avery Normal School buildings back. They wanted to create an archive and museum to save African-American history and culture in the South Carolina Lowcountry. The first president of the Avery Institute was the Honorable Lucille S. Whipper. She was a former member of the South Carolina House of Representatives from Charleston County.

To get support and reach their goals, the group decided to work with the College of Charleston. In 1981, both groups worked together to get a federal grant. This grant helped them plan programs and explore future options. From this planning, the idea of a research center was born. It would be a joint project between the Avery Institute and the College of Charleston. The College of Charleston then received the properties at 123 and 125 Bull Street. This allowed them to create the College of Charleston’s Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture.

The Avery Research Center: 1985–Present

In 1985, The Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture officially became part of the College of Charleston's academic programs. There were some delays because of Hurricane Hugo in September 1989. But the grand opening of the building happened on October 6, 1990. Today, the Avery Institute is a separate non-profit group. It helps support the Avery Research Center's museum, education, and public outreach programs. It also helps the center get new collections of historical items.

Museum and Historic Site

The Avery Research Center is a small museum. It has several rooms that show both permanent and changing exhibits. Each year, the staff at the Avery Research Center creates new exhibits. These exhibits use items from their archives, art, and rare old writings. The Avery Research Center also shows temporary art exhibits by artists from South Carolina and other parts of the African diaspora. You can take free guided tours from Monday to Friday. These tours are open to everyone.

Archival Collections

The Avery Research Center’s Archival Collections hold over six thousand original and secondary sources. This includes about two hundred collections of old writings. These collections can be small, with just a few items, or very large. The collections also have over five thousand printed items. These range from regular books and rare books to pamphlets and journals. There are also over four thousand photographs. Plus, there are hundreds of reels of microfilm, VHS tapes, and audio and video recordings in digital formats. You can also find dozens of artifact collections. These include items related to slavery, cultural items from West Africa, and even a collection of sweetgrass baskets.

You can search for processed collections and other items through the College of Charleston’s Addlestone Library’s online catalog. The Avery Research Center’s website also has an online guide to its collections. Some digital items are also available online through the Lowcountry Digital Library. Many digitized items from Avery are also shown in online exhibits with the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative.

Programs and Education

The Avery Research Center hosts many events and programs. These include public talks, workshops, movie showings, and performances. They also have annual conferences, special discussions, and exhibit openings. Sometimes, outside groups or the College of Charleston arrange events there. Events organized by the Avery Research Center staff usually focus on topics important to their mission. This includes teaching about African-American history, culture, and current issues in the Lowcountry and the wider African diaspora. The Avery Research Center building has event spaces like the McKinley Washington Auditorium. It also has other exhibit rooms and classrooms. The staff regularly updates the Programs calendar with upcoming events.

The Avery Research Center staff also leads education programs both at the center and in other places. These programs highlight important people, social movements, and historical events. They focus on African-American history and culture in the South Carolina Lowcountry. They use original and secondary sources from the Avery Research Center’s archives.

External links

- Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture http://avery.cofc.edu/

- Avery Institute http://www.averyinstitute.us/

- Lowcountry Digital Library: Avery Research Center Collections http://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/content/avery-research-center

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |